Theater Commentary: Portrait of the Artist as a Predator

By Bob Abelman

Is it possible to separate the art from the artist or, in the case of Rhode Island’s Contemporary Theater Company, the artist’s husband?

Venue for the Contemporary Theatre Company in Wakefield, Rhode Island. Photo: Wolf Matthewson

In 2017, when The New York Times published a series of allegations against film producer Harvey Weinstein from over 80 women who claimed that he sexually harassed and assaulted them, the hashtag #MeToo went viral and opened the floodgate for similar claims against others in the arts and entertainment industry. And the response, mostly firings and forced resignations, was dramatic and swift.

But since then, art itself has been prosecuted as well.

Most recently, the Justice Department released over 3.5 million emails relating to late sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein. Of the many names in those files, Nathan Wolfe – the now ex-husband of playwright Lauren Gunderson – appeared 589 times.

As the revelation that Wolfe and Gunderson had a connection to Epstein spread around the theater industry, one community theater – Contemporary Theater Company (CTC) in Wakefield, Rhode Island – announced on February 3 that it was cancelling its upcoming production of Gunderson’s The Revolutionists. In the play, according to the Dramatists Play Service, Inc., four women “lose their heads in this irreverent, girl-powered comedy set during the French Revolution’s Reign of Terror.” Gunderson has an impressive track record of writing women-centric stories that offer feminist voices. And her plays have made her the most-produced playwright in America for the past three seasons, according to American Theatre magazine.

Regarding the CTC, “This small and growing community playhouse is transforming itself into a cultural beehive in downtown Wakefield,” suggested Bill Seymour, who covers the theater for the local newspaper, The Independent. “It stands out among area community theaters with its broad and dynamic approach to engaging audiences,” said General Manager Maggie Cady in a recent profile in Motif magazine.

Playbill noted that the theater admitted that it was “not clear to what extent Gunderson shared her husband’s relationship with Epstein,” but it “will not produce work by Gunderson unless and until exonerating information does come to light.”

That is unfortunate, because of the whole “innocent until proven guilty” thing. But it is not unprecedented.

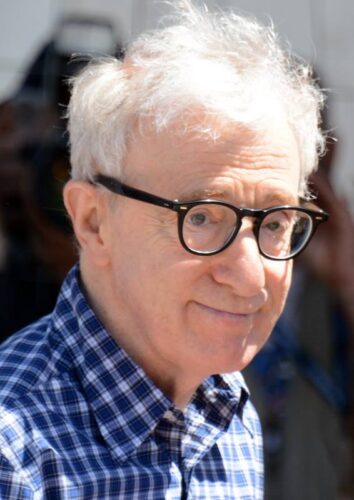

In 2018, Goodspeed Musicals in Connecticut – the theater known for giving Annie its start – announced that it had canceled Woody Allen’s Bullets Over Broadway from its fall schedule in light of sexual misconduct allegations. University of California, San Diego considered dropping a course called The Films of Woody Allen from its curriculum, which had been offered since the 1990s.

Woody Allen at Cannes in 2015. Photo: WikiMedia

Twenty-two scenes from the film All the Money in the World – about the 1973 kidnapping of John Paul Getty III – were quickly re-filmed at a cost of $10 million in a race to erase actor Kevin Spacey after the revelation of a history of homosexual misconduct and assault. And he was cut out of the remaining season of his hit Netflix series House of Cards.

The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. canceled a Chuck Close exhibit, amid allegations of sexual misconduct. One of his paintings, Self-Portrait 2000, was removed from the wall of Seattle University’s library.

Mayor Valérie Plante asked the body responsible for administering the Order of Montreal to look into whether Charles Dutoit, former artistic director of the Orchestre Symphonique de Montréal, should be stripped of the honor after several women came forward alleging they were victims of sexual harassment by him.

There are other examples.

The alleged acts are unconscionable. But is it possible to separate the art from the artist? Artists who have strayed from the prevailing moral code deserve what they get from the court of law, and those who have not sought forgiveness will no doubt get what they deserve in the court of public opinion. But can’t the work live on?

The answer is yes. And there is evidence of this.

Not long ago, the art of Amedeo Modigliani – an Italian painter and sculptor in the early 1900s known for portraits and nudes with elongated faces and figures – was given a high-profile exhibit in New York City. The artist led a debauched life that included womanizing and abuse of absinthe and drugs. He died, penniless, from tubercular meningitis. His lover killed herself, leaving behind their nearly 2-year-old daughter.

“The task of building up his legend I will leave to others,” wrote novelist Jean Cocteau – a friend whose portrait Modigliani painted – three decades after the artist’s death. “I can speak only of [his] noblest genius.” In 2015, one Modigliani nude fetched a record $170 million at Christie’s.

We haven’t stopped watching The Great Dictator because of Charlie Chaplin’s proclivity for and power over underage girls. We haven’t stopped reading Doctor Faustus because Christopher Marlowe had a proclivity for and power over young boys.

Dramatist Lauren Gunderson. Photo: Photo: Bryan Derballa

The New York Times film critic A. O. Scott argued that Woody Allen’s odious behavior may give us reason to revisit his work in a new light, but it does not detract from its aesthetic merit and cinematic genius.

And so the Contemporary Theater Company’s rash decision to cancel its production of Gunderson’s work is terribly misguided. Worse, it is an insult to its audience and sends the wrong message to surrounding regional theaters. No doubt the survival of a community theater, particularly in this day and age of across-the-board cutbacks to federal arts funding, is a precarious one. But why not champion Gunderson’s The Revolutionists – a play by a woman clearly stuck between a rock and a hard place about women stuck between a rock and a hard place – rather than fold to the imagined fear of subscriber cancellations and donor retaliation.

By all means, chastise the artist and applaud efforts that make short work of the careers of predators. But shouldn’t we leave the work in the galleries, on the stage, on the shelves, and in the cinemas to speak for themselves? If not, our cleaning house will need to start with Plato and Michelangelo. Fortunately, neither had wives.

Bob Abelman is an award-winning theater critic who formerly wrote for the Austin Chronicle. He covers the Providence theater scene for the Boston Globe.

Tagged: Contemporary Theatre Company, Lauren Gunderson, Nathan Wolfe

“Never trust the teller, trust the tale. The proper function of a critic is to save the tale from the artist who created it.” Wise words from D. H. Lawrence, a major twentieth-century artist who held fascist sympathies. Perhaps it should be amended, in the case of the Contemporary Theatre Company, to read: the duty of the critic is to defend the playwright from the company that would cancel her play.

What strikes me in this piece is the charge that the company folded out of “imagined fear of subscriber cancellations and donor retaliation.” This cowardice is symptomatic of too many of our theater troupes at a critical moment in American history and politics, when democracy is under lethal attack. The challenge to our “liberal” stages—to combat the forces of tyranny—is obvious, as is their failure to rise to the occasion. We have three more years of the Trump administration to come—will our theater artists and producers wake up before it is too late?