Book Review: “The Shores of Bohemia” — Cape Bohemian Rhapsody

By Peter Walsh

The Shores of Bohemia is clearly a labor of love, and a worthy one. But John Taylor Williams’ idea of “a group portrait,” however attractive, proves impossible to pull off.

The Shores of Bohemia by John Taylor Williams. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 368 pages, $35.

With the title of his book, The Shores of Bohemia, John Taylor Williams perhaps makes a small joke: the ancient kingdom of Bohemia, whose former territory makes up the bulk of today’s Czech Republic, was entirely landlocked. Williams’ subtitle, “A Cape Cod Story, 1910-1960” reflects his real subject — the extraordinary early 20th-century social history of three neighboring small towns on the Upper Cape: Wellfleet, Truro, and Provincetown, and the extraordinary group of artists, writers, critics, architects, journalists, editors, and radical thinkers of all types the area attracted over several generations.

With the title of his book, The Shores of Bohemia, John Taylor Williams perhaps makes a small joke: the ancient kingdom of Bohemia, whose former territory makes up the bulk of today’s Czech Republic, was entirely landlocked. Williams’ subtitle, “A Cape Cod Story, 1910-1960” reflects his real subject — the extraordinary early 20th-century social history of three neighboring small towns on the Upper Cape: Wellfleet, Truro, and Provincetown, and the extraordinary group of artists, writers, critics, architects, journalists, editors, and radical thinkers of all types the area attracted over several generations.

Williams, who also uses the name “Ike,” is a long-established Boston attorney, specializing in literary matters, and a literary agent. He found his splendid subject in the late ’60s, when he married into an old bohemian dynasty on the Cape and acquired a summer house in Wellfleet once owned by Mary McCarthy. There were still enough survivors of the Cape’s bohemian era around to share stories and legends that Williams thought that “a group portrait” of the Cape’s summer bohemians was a worthy topic for a book. It took him fifty-four years but it is at last between covers.

The English word “bohemian,” has little connection to the real Bohemia of Central Europe. Instead, the term comes from a nineteenth-century French misunderstanding and racial slur. Thinking that the Romani people arriving in France came from Bohemia, or at least through it, French xenophobes called them “Bohemiens.” But the term, as meaning people who live outside social norms and with little money, with rootless, riotous habits and a penchant for creative careers and radical politics, really took off with the publication of Henry Murger’s semi-autobiographical 1851 novel Scenes de la vie de boheme — the title could be translated into contemporary American as “Scenes of the Gypsy Life,” with approximately the same connotations. Many of Murger’s romanticized, colorful characters— poor young artists, writers, and would-be intellectuals living in the West Bank of Paris — were based on real people who were well-known around the hipper haunts of the city. Murger’s book inspired innumerable spin-offs and imitations, including the famous Puccini opera La bohème and the ’90s Broadway musical Rent. Mugler had immortalized and canonized the idea of the bohemian life.

Ike Williams’ bohemians are the avant-garde writers and artists, radical reformers, journalists, and political thinkers who congregated in Greenwich Village before the First World War. A series of environmental disasters made their seasonal migration to the Upper Cape, especially to Provincetown, feasible, assisted by rail service that linked the three Upper Cape towns to New York City. After the old growth forests had been cut down, the fragile Cape topsoil was exposed to the fierce Atlantic storms that blew much of it away, ruining the land for productive farming. At the same time, overfishing depleted local fisheries, which forced fishing fleets to travel further north to waters off Canada. The land’s desolation created the austere, sand-dune landscapes with scarce, scruffy woods, ponds, endless beaches, brilliant white light, and skies and water in saturated blues — the Cape landscape that is so beloved today.

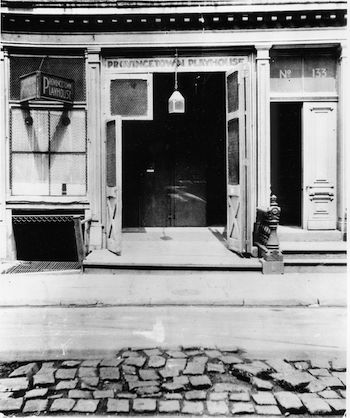

The economic fall-out of these environmental changes left the countryside dotted with abandoned farmhouses and the main streets of the towns with underused commercial buildings. The impoverished Yankee farmers and businessmen and Portuguese fishermen were happy to rent or sell, at very low rates, to the strange new people streaming in from the city. Provincetown became a kind of summer camp for the radicals and creatives of Greenwich Village. Whole restaurants shut down in the city in the spring and relocated to Provincetown for the summer, as did the famous Provincetown Playhouse and the German-American abstract painter Hans Hoffmann’s enormously influential art school, which trained a whole generation of prominent American painters.

Williams documents the enormously talented and committed (or, as he often puts it, “gifted”) artists, playwrights, poets, thinkers, radical journalists, musicians, and assorted nonconformists who, at some point or other, lingered on the Cape during the golden months of summer. They include a host of now-famous names; Eugene O’Neill, John Reed, Malcolm Crowley, Marsden Hartley, Louise Bryant, Edmund Wilson, Mary McCarthy, Tennessee Williams, and John Dos Passos, among many others.

Williams writes with energy and style and his cheerful, gossipy narrative moves along briskly, at least for the first half of the book, despite many digressions to explain the backgrounds, associations, and off-cape careers of his summer colonists. There is also plenty of sex, booze, nudity, and bad behavior along with some great parties. Perhaps as much as a third of the book actually takes place off-Cape: in New York and in as far-flung locations as Mexico City, Republican Spain, and Bolshevik Moscow. The complex networks Williams describes — of creative collaboration, love affairs, marriages, divorces, and falling outs in the few years between 1910 and the First World War — remain fascinating, even as the cast of his book expands from dozens to hundreds and their complicated entanglements begin to resemble the threads of a vast spider’s web spread over half the globe.

Like many books researched over many years, The Shores of Bohemia suffers from too many details. The narrative blurs, the cast of characters and their many affairs, marriages, and remarriages to each other eventually grow to be too much to foreground in the most capacious memory. As Williams unrolls the legends and memories of his in-laws and neighbors, he has trouble leaving anything out. At times, the book reads like a list of real estate transactions as properties are sold from one Cape bohemian to another, his descriptions of the hosts of “gifted” people begin to sound like digests of their distinguished resumes, and their many affairs and divorces suggest a Truman Capote tell-all.

Author John Taylor Williams, a long-established Boston attorney, specializing in literary matters, and a literary agent.

Williams never precisely defines what he means by “bohemia” or “bohemians” and his narrative lacks an overall premise. As he moves from the teens to the twenties, thirties, and forties it is clear that his demographics are shifting and his focus moves from the crowded summer streets of Provincetown to the dunes and kettle ponds around Wellfleet. The newer Cape migrants he describes arrive with money — from family trust funds or rich relations or the proceeds of a flourishing professional career — and they are no longer looking for cheap rents but a refuge — for a few summer weeks or the rest of their lives — from the world itself. They are more likely to live in custom-designed, modernist beach houses or studios than the dune shacks or old farms with no plumbing or electricity that housed an earlier generation.

Central figures of the second half of the book include Williams’ father-in-law, Jack (John Hughes) Hall, his four wives, and some of their children, including Ike’s own wife, Noa. Jack Hall, a 1935 Princeton graduate estranged from his wealthy family and his privileged background, married the daughter of a Cape bohemian painter in 1937 and moved to an old farmhouse on Bound Brook Island. Unlike the bohemians of an older generation, he lived on the Cape full time for most of the rest of his life, trying out various careers (novelist, fishing boat owner, painter) before establishing himself as a noted modernist builder and architect of summer homes, though he was never formally trained or licensed. Although Williams does not frame it this way, Hall’s progress both reflects and helps create the slow transformation of the bohemian Cape into an upper class summer resort and tourist destination, with a Mecca for affluent gay men in Provincetown.

Williams weaves a series of sub-themes in his later pages — the rampant alcoholism of the bohemians and the neglect of their children, the disintegration of radical politics in the split over Stalin and the persecution of leftists by the Federal government under J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI and Joe McCarthy’s HUAC, the area’s Jewish community, the creation of Provincetown’s summer refuge for gays, and the gathering of prominent modernist architects, designers, and teachers like Marcel Breuer, Anni Albers, Walter Gropius, and Eero Saarinen around Wellfleet in the ’40s and 50s. These sidebars restore some of the text’s interest though they also involve a certain amount of chronological backtracking and repetition of material covered earlier in the book.

Although the list of important names from these later decades is truly stunning, it is questionable how “bohemian” they really were. After all, many were pursuing prominent professional and mainstream careers even as they summered on the Cape. Williams is so eager to prove how extraordinary these Cape-dwellers and visitors were that he sometimes over-reaches. He includes, for example, the painter Edward Hopper, despite the artist’s distinctly conservative politics and notoriously anti-social behavior. Hopper’s visits to his Truro summer home and studio were for serious work, not for the drunken beach parties, nude swims, and love affairs so popular with the bohemians.

The Shores of Bohemia is not a work of serious scholarship or even of popular history. It is short on footnotes and, though Williams includes generous bibliographies for each of his four sections, the sources of his many anecdotes and legends are mostly unattributed.

The Provincetown Playhouse. Photo: Wiki Common.

And there are factual errors. Leon Trotsky was not murdered in Mexico City with “an ice pick” in 1940. The assassin, Spanish-born NKVD agent Ramon Mercader, did the deed with an ice axe. Financier J. P. Morgan was not “abroad” in September 1920, when a bomb explored outside his downtown New York offices, injuring hundreds and killing many of them. He was in the pastoral surroundings of Hartford’s Cedar Hill Cemetery, having died seven years earlier. All the standard sources say Tennessee Williams’ breakout play, The Glass Menagerie, premiered in Chicago in 1944, not in Provincetown, as Williams suggests. It is also difficult to believe that a “young” Katharine Hepburn or Bette Davis served as ushers in the Provincetown Playhouse in 1944, as Williams implies, or in any other year after about 1930. By the mid 40’s, both actresses were in their late ’30s, had been major movie stars for years, and had won Academy Awards for Best Actress (Hepburn in 1931/32: Davis in 1935). Although an unknown Bette Davis performed at the New York Provincetown Playhouse in 1929, just before the stock market crash shut the theater down, any appearance near a theater much later than that by either legend would have attracted a mob of fans.

Nature writer Henry Beston did not describe, in his classic The Outermost House, “the vast ocean’s healing powers” from a rented “one-room shack on the outer beach not far from Mable Dodge’s abandoned coast guard house.” Instead, in 1925, Beston purchased fifty acres of dunes in Eastham, about twenty-four miles south of Provincetown, where he designed and had built a small but comfortable two-room cottage he called the Fo’castle, There he took the notes that eventually became the book, published in 1928. Although Beston moved to Maine with his wife soon after the The Outermost House appeared, he owned the house until 1960, when he gave it to the Massachusetts Audubon Society. After being moved back twice from the eroding shore, the much honored literary landmark was swept out to sea by a hurricane in the winter of 1978.

Unfortunately, factual errors are like cockroaches. When you spot two or three without even looking, there are probably many more hiding in the woodwork.

The Shores of Bohemia is clearly a labor of love, and a worthy one. But Williams’ idea of “a group portrait,” however attractive, warm-hearted, and nostalgic for a lost world, proves impossible to pull off. There is too little room and too many figures to do justice to their rich and complicated lives. Inevitably, Ike’s bohemians fade into the fuzzy grays of those old-time team photographs or a faded snapshot of a long ago beach party.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.

The photograph of “The Provincetown Playhouse” is the theater in Greenwich Village where the Provincetown group relocated.