Book Review: “Hot Maroc” — A Moroccan Walter Mitty as Internet Troll

By David Mehegan

Hot Maroc is more of a three-ring circus than a drama, with a high-wire act at one end, tigers and elephants at the other, and scurrying clowns in the middle.

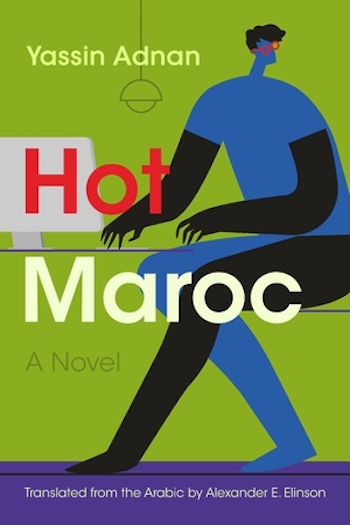

Hot Maroc by Yassin Adnan. Translated, from the Arabic, by Alexander E. Elinson. Middle East Literature in Translation. Syracuse University Press. Paper (available as an e-book). 409 pp. $29.95.

Morocco is in the northwest corner of Africa, not the Middle East, but this sad, pathetic, funny, tragic, thinly plotted, and madcap novel presumably fits with the Syracuse Press series because it is written in Arabic with a mostly Muslim cast. Set in the 1990s into the early 2000s, the narrative centers on Rahhal Laâouina, a timorous youth in Marrakech who blunders into the exercise of power that he enjoys but cannot control.

Morocco is in the northwest corner of Africa, not the Middle East, but this sad, pathetic, funny, tragic, thinly plotted, and madcap novel presumably fits with the Syracuse Press series because it is written in Arabic with a mostly Muslim cast. Set in the 1990s into the early 2000s, the narrative centers on Rahhal Laâouina, a timorous youth in Marrakech who blunders into the exercise of power that he enjoys but cannot control.

As the story begins, Rahhal, the only child of unhappily married Halima and husband Abdeslam, is a student of pre-Islamic Arabic poetry at Marrakech University. Too shy and passive to choose a topic for a senior thesis, he is paired by default with Hassaniya Ben Mymoune, a female classmate, to present a paper on an ancient poet. Although he is knowledgeable, at her initiative the paper they put together is largely plagiarized. She is disagreeable and bossy, yet after college they marry (her idea, though she shows no sign of feeling for Rahhal) and both begin to work at a small private school in Marrakech, the Atlas Baby Cubs Private Elementary School — she as an administrator and he as a typist and all-around fixer.

This might be the sort of job a person like Rahhal would keep for life, but the owners of the school, Emad Qatifa and his wife, Hiyam, decide to set up a cybercafé on one floor, open to the public for an hourly fee. In a place and time where hardly anybody has personal access to the Internet, the café becomes a magnet for the menagerie of characters that populate the book. Rahhal becomes the manager, and soon is fascinated with Hot Maroc, a news website on which anyone can post any sort of comment on the content, and later even more fascinated when Facebook appears.

Rahhal is a Moroccan Walter Mitty, who dreams of violently demolishing his tormentors and competitors and conquering the women he craves. Like Mitty, he has almost no life outside the café. Even his wife disdains and ignores him. On Hot Maroc and Facebook, Rahhal creates a number of personae (Son of the People, Abu Qatada, Mounir Raji, 24/7 Samir, even a sexy woman named Hiyam) and sometimes uses these figures to slander or destroy his enemies — or just those he dislikes, such as the harmless poet Wafiq Daraai, whose success and reputation he resents, or Fouad Wardi, the former classmate who suspected his plagiarism. He never writes under his own name. Along with his own writings, he snoops in the personal accounts of all the other customers in the café.

Some of his outspoken avatars, unfortunately, run afoul of shadowy political powers, including the state security and police. They haul Rahhal in and demand to know the real identities of some of the writers, not suspecting that he is them. Son of the People is regarded as especially dangerous. Rahhal manages to weasel out of their pressure, but then comes a switch — they tell him that he must write what they want him to write, denounce and praise whomever they wish, and in return he will be on a mysterious payroll. He eagerly accepts the offer, and begins to salt away cash, without telling Hassaniya, of course.

Although Rahhal is the protagonist, he is not necessarily the most important or interesting character. He serves mainly as the eyes through which we watch the other characters, all of whom connect with the cybercafé, although the majority of their affairs occur outside it.

I’ve given here the lightest possible plotline, but then Hot Maroc doesn’t really have a thoroughgoing, spinal plot that resolves itself in the end. It’s more of a three-ring circus than a drama, with a high-wire act at one end, tigers and elephants at the other, and scurrying clowns in the middle. Although an enormous amount of action occurs between and among characters, scheming and counterscheming, amid intricate analyses of motivations and relationships, you might find yourself, hundreds of pages in, wondering, “Where is all this going?”

More than anything, Hot Maroc is a total-immersion report on Moroccan society, culture, and politics around the last century-turn. Not all of society, however; rather, the urbanized, middle-class, relatively well-educated society. This is a city book. The rural poor of Morocco are not in evidence. Although there is a great deal of politics in the book, mostly in the form of the rhetoric and clashing machinations of political parties, actual government never appears. The bulk of the action, as I said, involves quarrels, resentments, petty attacks and counterattacks of the various characters. There seems to be no unity, no solidarity, and no idea of common ground. To paraphrase Tip O’Neill, in this book all politics is personal. And what an unself-critical, small-minded crew! There are a few admirable characters — or possibly only one, the goodhearted Nigerian café customer named Yacabou. Not a Moroccan, but a foreigner.

I found Hot Maroc to be a hard book to read. It has an enormous cast. I counted close to 40 active characters, and many others on the fringes. It is difficult to get a grip on many of these figures because they are given the lightest possible descriptions, and their characters are announced, rather than revealed, by the narrator. There is also little attention or interest in the mise-en-scene. Marrakech must be as colorful, teeming, and fragrant as any North African city, but Adnan is not much interested in that which is outside the brains, voices, and antics of his characters. We might as well be in Cleveland.

The book has three named parts and 88 chapters. Most are two or three pages in length, five at the most. Only rarely does one follow another in action or setting. Most start with a new situation or character (or one who last appeared earlier in the book), leading one repeatedly to ask, “OK, where am I now? Who is this again?” Perhaps the right word is not “chapter” but “vignette.” For the reader it is not a matter of following a stream or street, but more like a game of hopscotch. As soon as you get some forward motion, you’re cut short and sent to another person and situation. Much of the action is taken up with petty feuds and score-settling, by Rahhal and others.

A character list at the beginning would have shown consideration for the English reader; I resorted to making my own. As noted, some of Rahhal’s Internet personae have the names of real people, so there is Hiyam the real person, and Hiyam the invented. The avatar Abu Qatada is taken from a real character, but that sobriquet is actually a sneering nickname for a Muslim fanatic at the café whose real name is Mahjoub Didi. There are generational echoes: Emad Qatifa and his father, Hajj Emad, Shihab Eddine Assuyuti, the father of Qatar Eddine (oh, and Qatar Eddine also has a nickname: Abdelmissih), and Oum Hassaniya, mother of Hassaniya. Alexander E. Elinson announces in his translator’s note that he decided not to bother with a glossary, so we are left to guess (or discover with an online search) that “Oum” is an Arabic honorific for a mother, “Hajj” is an honorific for one who has made the pilgrimage to Mecca, and “caid” is a local or tribal head-man or leader.

Then there are the animals. Rahhal believes that every person has an animal analogue. Once he assigns an animal name to a person, he (and the narrator) uses it interchangeably with the actual name. We’re told that people see Rahhal as a rat. However, he sees himself as the Squirrel. His mother is the Pelican, his father is the Mantis, a female college classmate is the Cow, Hassaniya is the Hedgehog, a sexy waitress at the Milano Café is the Lioness. The hyena, the greyhound, the lizard, the gerbil, etc. The Lioness, by the way, is Rahhal’s mental model for his online avatar Hiyam. Meanwhile, he has a secret lust for the real Hiyam, has fantasies of eliminating Emad, her husband, and gets himself in trouble by whispering her name during sex with the Hedgehog. (Ouch.) Is this all clear?

I am not qualified to judge the accuracy or quality of Elinson’s translation, but found his use of American cliché phrases distracting: “from the get-go,” “hone in,” “wannabe,” “the rest is history,” putting in “his two cents worth.” Is there some reason we need to hear these people in American-style voices? Arabic is doubtless as beautiful and wonderful as Elinson says it is, so why these irritating clinkers?

The book has relatively little dialogue. Mostly we get the relentless arch voice of the narrator in long paragraphs, often a page or more in length. Sentences, too, tend to be extended and elaborate. Perhaps this is the nature of Moroccan Arabic, but it makes for page upon page of formidable walls of type.

The narrator is a mysterious figure. He abhors Rahhal, a sneaky coward who “only destroyed his adversaries and opponents in his dreams.” Hot Maroc “was more than just a news site to Rahhal. It was a space for him to express himself and defame others.” The narrator sometimes slips into the present tense to abuse Rahhal, as if the squirrel were able to hear him. “Picture, Rahhal, that you had children. Would you give mankind a wonder of a little angel with a sweet smile? Would your baby be like the child in the Dalaa and Pampers ads? No doubt you’ll give birth to a rat that looks like you. An indistinguishable squirrel with ratlike eyes, running and howling behind you.”

Author Yassin Adnan. Photo: courtesy of the artist

On Rahhal’s conduct in the cybercafe: “Yeah, Rahhal. You see them [the customers] moving in front of you like puppets. None of them knows that they’re in your pocket. Their real and made-up names. Their interior and exterior lives. Their dreams and their delusions. Their ruses and their wild, made-up tales. Their innocent virtual friendships and their illicit electronic adventures. Everything is in your pocket, Rahhal, but you’ve got to be smart about it. Be extremely careful that these secrets remain hidden. Keep them to yourself, you scrawny squirrel…. So Rahhal enjoyed spying on the members of his new family with just enough care to give each one of them a feeling of total safety.”

Who is this overbearing narrator? The author? Why would he execrate a character he has invented? The narrator could not be an unidentified character, because he is omniscient and knows what is in everybody else’s mind and past, as no member of the cast could be. Is it Rahhal himself, speaking to and of himself? Unlikely, because he shows no moral self-insight or eloquence. The interjections of this one-person Greek chorus, whoever it is, suggests that the author cannot forebear to break in and vent his fury at the despicable behavior of his characters.

Syracuse Press’s flap copy tells us that Hot Maroc is “an infectious blend of humor, satire, and biting social commentary … a portrait of contemporary Morocco.” Perhaps Moroccans and other Arabic-speakers were in stitches, but I confess I did not laugh much. It’s mostly a depressing scene, filled with ignorance, small-minded malice, cruelty, and religious hypocrisy. And yet, as with any novel, an undertone can be heard by anyone, from any society, if one steps back from the maelstrom of characters, motivations, and subplots, and shuts out the intrusive narrative voice. It is an undertone of pained longing for honesty, decency, and perhaps authentic selfless patriotism.

Over the course of this long book, Rahhal never grows, changes, reflects, or does anything to elicit our sympathy — he is a Machiavellian cipher. Are we to take this as the state of Moroccan society? But at the very end of the tale, real life and death break in unexpectedly upon him and there seems a chance — small to be sure — that he will find something finer in himself. If such a creep can have an awakening, there must likewise be hope, in Yassin Adnan’s mind, for the world he lives in.

David Mehegan last reviewed Mario Vargas Llosa’s Harsh Times for Arts Fuse. He is the former book editor and literary writer for the Boston Globe. He may be reached at djmehegan@comcast.net.

Tagged: Alexander E. Elinson, David Mehegan, Hot Maroc, Syracuse University Press