Film Review: “On Broadway” — A Love Letter to the Return to Normal

By David Greenham

If the theater really mirrors life, then you can bet we’re in for some drastic changes and adjustments, even on Broadway.

On Broadway, produced and directed by Oren Jacoby. Opening on September 3 at the Coolidge Corner Theatre, Brookline, MA.

New York’s Theater Row. Photo: Kino Lorber.

“The whole concept of Broadway,” Tony-award winner (The Audience) Helen Mirren says, “has this very romantic, very heroic, very legendary kind of feel to it.” That’s the premise of On Broadway, Oren Jacoby’s love letter to New York’s commercial theater.

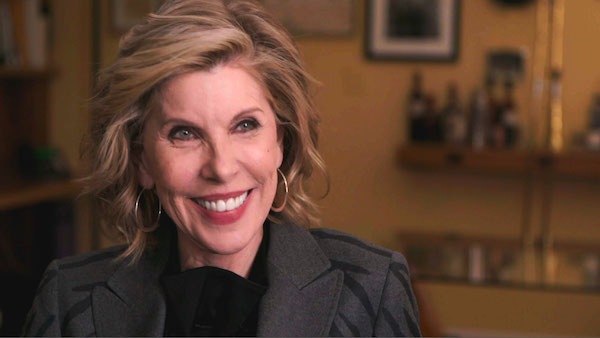

In the 85-minute documentary, Mirren is part of a talkfest made up of a who’s who of Broadway royalty, including George C. Wolfe, Lynne Meadow, James Corden, David Henry Hwang, Tommy Tune, Ian McKellen, Hal Prince, Christine Baranski, Michael Eisner, Cameron Mackintosh, Oskar Eustis, Jack O’Brien, and many others, including Gianni Felidi, maître d’ at Sardi’s.

The documentary was made during the 2018-19 season in which 38 shows opened. The odds were that 75 percent of them would fail. In addition to interviewing an army, director Oren Jacoby takes a deep dive into the staging of Richard Bean’s comedy The Nap, which is about the game of snooker. The doc plays particular attention to the fact that the cast included transgender actor Alexandra Billings. The production opened on Sept 27, 2018, and closed six weeks later.

For Broadway fans, the documentary includes an overview of commercial theater history, from the mid-20th century on. That invites some excellent clips of productions and interviews with past stars. Best among these short milestone tales is the story of the development of A Chorus Line, as well as the brilliance of dramatist August Wilson and his Pittsburgh plays. Jacoby and his team manage to make the 1982 battle over the destruction of theaters on 45th and 46th street and Broadway still seem raw. The victims included the Morosco Theatre, which hosted the original productions of Our Town, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, and Death of a Salesman; the Helen Hayes (formerly the Fulton), which had hosted the original productions of Abie’s Irish Rose, Arsenic and Old Lace, and Long Day’s Journey Into Night; and three historic movie houses: The Bijou, The Victoria (formerly The Gaiety), and the oldest of the five, The Astor. They were all torn down to make way for the Marriot Marquis hotel and theater.

Ian McKellen, one of the talking heads in On Broadway. Photo: Kino Lorber

The documentary doesn’t reference The Theatrical Syndicate’s early commercial control of nearly all the major theaters in New York and across the country at the turn of the 20th century, but there are references to the current cabal that is controlling the Great White Way: the Shubert Organization (the family that helped break up the syndicate in the ’20s and now operates the most Broadway theaters), The Nederlander Organization, Jujamcyn Theaters, and the new corporate mouse on the block, Disney. Is anyone surprised that — then and now — money (especially profits for fat-cat backers) is the most important measure of “making it” on Broadway? As one producer points out in a voice-over, “Success is a funny thing. The exhilaration of theater is challenging as well as entertaining. What makes money and what represents the craft at its highest art form are not always the same thing.”

There are also bouquets delivered to nonprofits, such as Joe Papp’s Public Theater and The Manhattan Theater Club. Credit is also given to the role Broadway played in the recovery of New York City in the I Love NY campaign during the ’80s.

But Broadway’s resurgence inevitably calls for more investment, which raises expectations regarding the size of profits. It is suggested that Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Cats marked an important milestone when it came to funding and excess. In 1980, the Shubert-owned Winter Garden Theatre at Broadway and 50th had just undergone a renovation. An agreement to bring Cats from London required the interior to be gutted (again!) and redesigned in order to accommodate the junkyard setting for Andrew Lloyd-Webber’s smash hit.

George C. Wolfe notes that it is the moment where Broadway started pricing itself out of accessibility. He calls the era of British spectacle “the pageant stage.”

But the documentary also notes a creative split during the same period. Veteran writers and newcomers offered fresh perspectives. As the AIDS epidemic devastated New York, especially the cultural community, dramatists such as Neil Simon began writing different kinds of plays, and the challenging works of August Wilson, Athol Fugard, and Tony Kushner were welcomed by eager audiences.

The late dramatist August Wilson in On Broadway. Photo: Kino Lorber

Producer Manny Azenberg was one of the financial leaders of the new play movement of the period. He explains that “the theater, for some of us, is where, instead of going to the church or the synagogue, we felt that you had a social, political responsibility; plays had to be about something.”

As the New York City renaissance continued to grow, the effort to “clean up” Times Square gained momentum. The 42nd Street development project moved 400 businesses in order to make way for something new. Disney’s CEO, Michael Eisner, saw an opportunity to make even more money. With the help of tax breaks from the city, Disney created a new commercial juggernaut on Broadway; the corporation took over one theater and rented others, filling the stages with adaptations of their popular films. The transformation of Broadway into a perpetual spectacle, part of a nonstop branding campaign, was complete. Jack O’Brien sums it up: “We’re like Las Vegas now.

On Broadway acknowledges that the rising cost of tickets continues to be an obstacle. Tommy Tune quips that when he first came to New York in 1976 the top ticket price was $9.90 ($47.50 in today’s dollars). No one mentions that the average ticket price for the mega-hit Hamilton at the end of the 2018-19 season was $375.

When it opened in 1996, Rent charged $20 a ticket for the first two rows of seats. Young people slept outside the theater to have their shot. In-person and online lotteries have become commonplace. The Theatre Development Fund’s TKTS venues work with theaters to sell last-minute discount tickets. Hamilton comes in for praise: once a month, prior to the pandemic, the show’s entire house was made available to inner-city kids for a Hamilton ($10).

But the outlier discount ticket efforts are too few and halfhearted to combat rising costs and mounting desires for more profit. Most of those interviewed in On Broadway recognize the problem but offer few solutions.

“If we don’t have a big tent, we’re not going to have a theater that matters to America,” offers Public Theatre head Oscar Eustis. Tony-winning producer Robert Fox goes further: “I find gouging people unappealing, and I think people are being gouged. But it’s not called show charity, it’s called show business.”

Christine Baranski in On Broadway. Photo: Kino Lorber

Ultimately, and with pride, the documentary points out that 2018-19 was the most successful year in Broadway history for both attendance and gross profit. Still, there is a dark side to the huzzah. Azenburg proclaims that “we are now evolving into something that looks much more like a theme park than a cultural center.”

Perhaps, in the post-Covid world, whenever that arrives, changes will come, a balance will be found, and Broadway will once again thrive as art rather than big business. Who knows? Whatever happens, it seems unlikely that it’ll be exactly the same as it was. On Broadway effectively points out that circumstances are always changing — norms are rejected, adaptations accepted. If the theater really mirrors life, then you can bet we’re in for some drastic changes and adjustments, even on Broadway.

Let’s hope that, amid the transformations to come, one experience will remain: the promise made by Broadway, film, and television star Christine Baranski: “When you see a great performance, it is a spiritual experience.”

David Greenham is an adjunct lecturer of Drama at the University of Maine at Augusta, and is the executive director of the Maine Arts Commission. He has been a theater artist and arts administrator in Maine for more than 30 years.