Fuse Book Review: “Country of Ash” — Another Essential Holocaust Memoir

We become increasingly aware that we are in the mind of a doctor who has taught himself to observe carefully, who has an amazingly strong will to survive, and who chooses not to waste precious time and energy on anger or revenge.

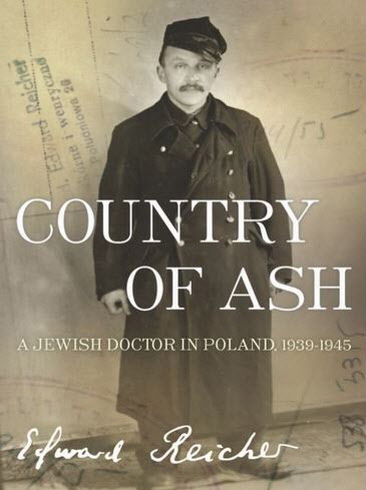

Country of Ash: A Jewish Doctor in Poland, 1939-1945 by Edward Reicher. Bellevue Literary Press, Paperback, 256 pages, $16.95.

By Roberta Silman

Do we need to read another book or see another play or movie about the devastation of the human spirit by the events of the Holocaust? That is the question you may well be asking yourself as you start to read this review. It is a question I have asked myself many times, and each time, as I weigh its pros and cons, I realize how impoverished my life would be if I had not read Primo Levi or Paul Celan or Nelly Sachs or Imre Kertesz, if I had not seen Shoah. Or if I had not seen the anguish of our fabulous guide in Budapest as she recently described the brutal slaughter of almost a half million (the number could be even more) Hungarian Jews in the last three months of the Second World War. For each story has its own uniqueness, its own voice, its own insights. And each story is a reminder of the capriciousness of history, the unfathomable human penchant for cruelty, and also the daring of those who insist on justice and goodness despite incredible obstacles. For these are stories that get to the core of what it means to be human – that is why we are so drawn to them, and why the answer to my question is: Yes.

In his wonderful memoir The World of Yesterday, Stefan Zweig describes life in late 19th century Vienna as:

a world without haste, [a world where] people no more believed in the possibility of barbaric relapses, such as wars between the nations of Europe, than they believed in ghosts and witches; our fathers were doggedly convinced of the infallibly binding power of tolerance and conciliation. They honestly thought that divergences between nations and religious faiths would gradually flow into a sense of common humanity, so that peace and security, the greatest of goods, would come to all mankind.

With the First World War all that was called into question, and by the end of the Second World War such ideas were shattered forever. And now, in light of what has happened in our new century the ideas of security (in its old sense) and peace seems almost laughable.

Still, it is also human to hope. So that is why we read, hoping that if we know as much of the story as we can, we can at least pay homage to those who suffered and lived to tell it. And, perhaps, somehow prevent it from happening again, somehow make the world a more humane place.

Edward Reicher was born in Lodz, Poland in 1900, and became a doctor, lucky not only in his profession, which he loved, but also in his personal life which was more than comfortable and filled with the joys of family life with his wife Pola and small daughter Elisabeth. That not only he, but his wife and daughter survived, first the Lodz ghetto and then the Warsaw ghetto and then for a time passing as Aryans before they were free, is nothing short of a miracle. Beginning in 1944 he kept a diary and in the 1960s he “reconstructed it.” When his daughter found it after his death in 1975, she decided to publish it, and it has come out in Polish and French, and now in English, translated from the French by the well-known writer and translator, Magda Bogin, who refers to Elisabeth’s reasons for preserving the past in her beautiful Foreword:

“Assimilation may overlap with an effort to adapt in order to survive,” [Elizabeth] wrote in the psychoanalytic journal Controverses. “But pain left unexpressed is a mute witness, like a burning ember ready to flare up again. That witness, like a transfusion, is transmitted from parents to children.”

The book is plainly written and filled with facts rather than feelings. Starting with his admission that “the outbreak of war caught me entirely by surprise,” Reicher tells his story almost as if it was happening to someone else. There is weather, there are guns and sirens and filth and pain, there is typhus, the scourge of all ghettos, there is humor and sarcasm, there is music and beauty, there is love and loyalty, there are kind strangers and brutal ones, there are former friends and colleagues who help him, and some who are cruel beyond imagining. But with every observation Reicher shares with us, we become increasingly aware that we are in the mind of a doctor who has taught himself to observe carefully, who has an amazingly strong will to survive, and who chooses not to waste precious time and energy on anger or revenge.

But we also see that very mind expanding to accommodate things he would never have believed, like the madness of Chaim Rumkowski, the “King of the Jews” in the Lodz ghetto, or the bravery and ingenuity of those who tried to save the beautiful Yola Glicenstein in the Warsaw ghetto (which could be regarded as a rehearsal for the uprising there in 1944), or the incredible delusions of Leon, the barber who cut the hair of the Gestapo yet truly believed they would find a place for him on the French Riviera at the end of the war.

What makes this diary so powerful is that Reicher dwells on very little – for it is all so crazy – and tells the facts and his story with dispatch, so that we are so caught up in events that we begin to feel as if we are living them with him, that we have somehow been dropped into a Beckett or Ionesco play where absurdity at its most extreme is reality. Nothing makes sense or is predictable – people he thought he could count on disappoint, others he barely knew surprise him and come to his aid. And always there is the eternal problem of the haves and have nots – those with money (like Reicher) have a better chance at survival, and he does not forget it and pays when he has to. But no amount of money can circumvent the deep-seated hatred of Jews that propels everything, during the war and even after when he returns to Poland.

Through it all Reicher maintains his dignity and refuses to become like his enemies. For if someone like Reicher had fallen into the trap of fighting bestiality with his own beastly feelings, he never would have lived. But surviving had its price – as we well know from the suicides of Levi and Celan and Stefan Zweig – and it is clear as the book progresses that Reicher is, before our very eyes, teaching himself not to feel so much, because he knows that too much feeling could lead to his own and his family’s downfall.

In some ways the saddest part of this book occurs towards the end. There, at the close of 1944, after the Warsaw ghetto uprising had been crushed, but where people knew the Germans were losing, Reicher is being treated at the hospital in Piastow for wounds suffered in a bombing in Warsaw and posing as Jan Szewczak “with a huge mustache, a dirty black [railwayman’s] uniform, and a battered railwayman’s cap.” Listening to his fellow patients, Reicher observes that little in his native country has changed.

The Jews were to blame for everything. From poisoning wells to committing ritual murder, nothing had changed since the Middle Ages. In the minds of many of the patients on my ward, the Jews were like evil spirits who wandered the earth with the intention of bringing misfortune on humanity. If there were no Jews, the world would be carefree and happy. There would be no murder, crime, war, or disease.

Still, even after hearing Jews defamed and also defended, he and his family choose to return to Lodz when they are freed by the Russians. But that proves even sadder. The concierge of their building wants money for “protecting” their apartment even though he has sold everything in it. And when he goes back to his childhood home:

The naked walls of my father’s house stared back at me. Nothing remained but memories. My parents’ bed was still in their room. This was where my bedridden mother had spent seven years until her death. I saw it with the eyes of my soul, because this vast apartment was now cold and impersonal. I was lost in the vibrant, piercing past. The present was empty.

And after the pogrom in Kielce in 1946 when surviving Jews were massacred by Poles, Reicher finally decides to leave Poland: “I sold my house in Ruda Pabianicka for a fraction of what it was worth. I had spent my best years there, and during the dark days of the occupation I had dreamed of spending the rest of my life there. It was only a dream.”

After being foiled for years in his attempt to emigrate, Reicher and his family finally leave Poland in 1960 and settle in Germany. Irony of ironies, but where Imre Kertesz also lives. There he became a dermatologist again, tried to live as normally as possible, but, I think, knew he had to somehow leave something tangible that would reveal all he had gone through. In 1961 he was a witness for the prosecution in the war trial of Hermann Höfle, chief of Operation Reinhard in the Warsaw Ghetto and one of the worst murderers in the Nazi war machine. After that he decided to “reconstruct” his diary into what has become this small but important book.

When I closed it, I felt I had to go back to Reicher’s Introduction which really best expresses the essence of this noble man:

It isn’t hard to die, but it is hard to live while fighting evil. I have forgiven those I met after the war who dealt me the fiercest blows during that lawless time. To this day, some of them still walk freely in the world. If I forgave, it was at the request of sincere Christians, those who saved me. They all had faith in another justice that would one day punish the criminals. . . .

The man who has written this memoir has aged; his hopes no longer belong to him. He has entrusted them to the next generation, for only they can attempt to overcome the vile actions of the past.

Only the young can choose to do what whole generations of their forebears failed to do: embark on the path of a true and just humanism.

In that spirit we can give thanks to all who worked to bring Country of Ash into our lives, then read it with care, and heed its warnings.

Roberta Silman is the author of Blood Relations, a story collection now available as an ebook; three novels, Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again; and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. She writes regularly for The Arts Fuse and can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: A Jewish Doctor in Poland, Country of Ash, Edward Reicher