Theater Review: “Waiting for Godot” — Dramatizing the Residue of Resilience

This remains a vision of a dystopian universe, but in the hands of these performers “Waiting for Godot”‘s angst exudes as much antic warmth as it does cold angst.

Waiting for Godot, by Samuel Beckett. Directed by Judy Hegarty Lovett. Co-production between Gare St Lazare Ireland and the Dublin Theatre Festival, presented by Arts Emerson at the Paramount main stage, Boston, MA, through November 10.

By Robert Israel

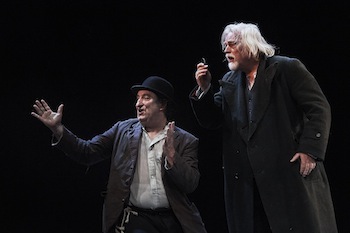

(L to R) Gary Lydon as Estragon and Gavan O’Herlihy as Pozzo in the Gare St. Lazare Players production of “Waiting for Godot.” Photo: Ros Kavanag.

This production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot takes an existential masterpiece of dramatic literature and gives it humanity. Under the direction of Judy Hegarty Lovett, the five member all-male cast brings a fresh perspective to this portrait of lost souls moored on a lunar landscape bathed in full moonlight. Yes, Beckett’s trademark despair emerges, but so does his humor. This is a vision of a dystopian universe, but in the hands of these performers its angst exudes as much antic warmth as it does cold angst.

Sixty years have passed since En Attendant Godot‘s premiere production in Paris. Five years later, Beckett translated his work into English, and the play made its journey to London and, eventually, to New York. The script has since been performed around the world, translated into many languages (including, most recently, Yiddish, where the Yiddish Repertory production in New York was dubbed a “kvetchathon” by the weekly Jewish Forward). An army of famous actors have appeared in Godot, including Bert Lahr, Zero Mostel, Burgess Meredith, Brian Denehy, Steve Martin, Robin Williams, Bill Irwin and F. Murray Abraham. A Broadway production, starring Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart, opens at the Cort Theatre in New York on November 24.

What the Gare St. Lazare Players Ireland bring to the work is its distinct connection to Ireland, Beckett’s ancestral home, which he abandoned. In 1939, the author declared that he preferred “France at war to Ireland at peace.” Yet, like James Joyce, a fellow Irish ex-patriot whom he befriended in Paris, he never completely exorcised his Irish demons. Thanks to this production, moving glimpses of the Old Sod itself flicker through the emptiness.

Beckett’s terse description of the play’s setting is now legend: “A country road. A tree.” As envisaged by set designer Ferdia Murphy, that road is pocked by craters where Vladimir (Conor Lovett) and Estragon (Gary Lydon) spend their days and nights, lost, dazed, displaced. They could be gypsies, one supposes, but they are neither exotic or ethnic; there is no campfire, no women, no music (they can scarce recall the verses to a song). They are refugees from some sort of widespread disaster that has reduced this landscape to dank and dark nothingness, where they squat with garlic breath and stinking feet.

Sixty years ago, audiences could identify with this landscape as the continent of Europe, still recovering from World War II, devastated by incendiary bombs that transformed vast acres of town and country into hellholes. Only a scant eight years before atomic bombs had obliterated Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

(L to R) Gary Lydon as Estragon, Conor Lovett as Vladimir in the Gare St. Lazare Players production of “Waiting for Godot.” Photo: Ros Kavanag.

Memories of that worldwide war are no longer as visceral, but we see images of similar wastelands piped onto our cable television news programs every night. This production alludes to devastation, facing that kind of despair straight on. But it accentuates the aspects of the human spirit that make due with scraps, that survives the unthinkable with a residue of resilience. That is no easy feat, yet through the rhythmic patter of speech, carefully accented to land on our ears with the impact of stripped and bare poetry, we become tantalized. The actors speak to one another, around one another, and through one another. They repeat phrases. They emphasize some words, omit others. There is a an insistent bleat of a beat, but there are also abundant silences where we are forced to replay in our minds what we just heard, to listen to what was said in the form of resonate echoes.

The scenes that introduce us to Pozzo (Gavan O’Herilhy) and his slave Lucky (Tadhg Murphy) are the most unsettling, yet thanks to the ensuing comedic posturing and the clown-like antics we see the absurdity of this sad couple, and perceive its fragilities. They, too, are lost, yet appear more like sadistic escapees from a Hieronymus Bosch painting, hobbling about a forlorn landscape. Their interactions with Vladimir and Estragon add emotional depth to their pathetic gamesmanship, showing us there is humor even in the most abusive of arrangements.

Throughout the production, I kept thinking of my neighbor Anthony, an Irish immigrant now in his seventies, who gets by performing odd jobs (repairing roofs, cutting firewood). He has recently battled cancer, automobile accidents, and uncertain financial upheavals with a sense of spirit I find enviable. Like the strange characters in Beckett’s play, Anthony remains buoyant, even optimistic, and he sees the light amid the darkness. Beckett’s characters are miserable, malodorous, lost, troubled, and despondent. But they are also survivors, like my neighbor Anthony. They carry seeds of humanity into the moonlit world they inhabit. They may not get around to planting them, they don’t expect things to change, they may ponder suicide, but they’ll never follow through with it. Like all of us, they are destined to live and to wait out their hours and days doing the best that they can to endure.

Robert Israel writes about theater, travel and the arts, and is a member of Independent Reviewers of New England (IRNE). He can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com