Poetry Review: The Dark of Love –The Poetry of Patrizia Cavalli

If Patrizia Cavalli’s poetry is egocentric, even probably autobiographical, its narrator shows a detachment enabling her to observe herself from one remove, even when she describes herself in the élans of attraction.

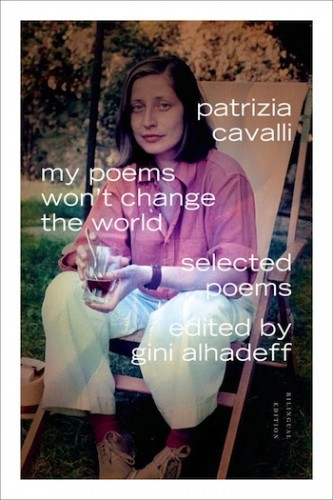

My Poems Won’t Change the World: Selected Poems by Patrizia Cavalli, edited by Gini Alhadeff, translated from the Italian by Gini Alhadeff and others, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $30 (cloth).

By John Taylor

How invigorating to have so much poetry by Patrizia Cavalli (b. 1947) now available in English. Although some of her work has previously appeared in translation, notably in a selection similarly entitled My Poems Will Not Change the World (Exile Editions, 1998), this new gathering goes well beyond that pioneering volume. Besides poems chosen from her title collection, which was first published in Italian in 1974 as Le mie poesie non combieranno il mondo, here are many more samples from The Sky (1981) and The All Mine Singular I (1992), as well as more recent verse from Forever Open Theater (1999) and Lazy Gods, Lazy Fate (2006).

Modern Italian poetry, long dominated by outstanding Hermetic Poets (the best-known of whom is Eugenio Montale, which is by no means to forget Mario Luzi, Giuseppe Ungaretti, Leonardo Sinisgalli, Salvatore Quasimodo, and others), often gives an impression of lyric intellectuality. Or should one perhaps say “intellectual lyricism”? There is definitely music in such verse, while the imagery can be intricate, even difficult to the point of obscurity; in a word: hermetic. Much of this Italian hermetic verse is fascinating to read because it reflects outside reality as it passes through subjective filters in unusual ways.

As the title of the collection The All Mine Singular I boldly states, subjectivity also lies at the heart of Cavalli’s poetics. Yet in comparison to Montale’s poetic use of the ego, she explores the sensibility of the “I” in a less flamboyant, more meditative mode.

In his important essay (2006) on her, the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben first distinguishes the two “opposing tensions” of poetry considered as a “force field”: “the hymn, whose contents consist of celebration, and the elegy, whose contents consist of lamentation.” Agamben argues that twentieth-century Italian poetry is mostly elegiac and emphasizes the preeminence of the “elegiac orthodoxy” associated with Montale.

Underscoring Cavalli’s “incomparable mastery” in regard to caesuras, internal rhymes, and enjambments, and praising her “stupefying” prosodic know-how, the philosopher adds that her poetic language is perhaps “the most fluid, continuous, and colloquial in twentieth-century Italian poetry.” He concludes that hymn and elegy blend in her verse, the celebrative aspects “liquefying” into lamentation and the lamentation “immediately becoming hymn-like.” To his mind, this is what is original in her writing, in both its music and meaning, in regard to the Hermetics.

This dichotomy can indeed be kept in mind when reading such deceptively simple poems as this two-liner:

Thinking about you

might let me forget you, my love.

Penso che forse a forza di pensarti

potrò dimenticarti, amore mio.

Among subtle effects of assonance, here is an internal rhyme (“pensarti” / “dimenticarti”) that becomes a repeated “you” in Mark Strand’s version. Above all, an elegiac potential emerges at the onset when the narrator declares that she is “thinking” about this “you” (who is therefore distant, unreachable) and then raises the question of “forgetting” him or her. Yet these elegiac contents are then swept up, enveloped as it were, in the celebrative invocation “my love.”

The psychological insight informing these lines is stunning. Thinking about a loved one implies forming mental images that run the risk of oversimplifying, falsifying or even essentially effacing the genuine, living, vibrant, evolving “you.” There is a danger that the real “you” can be mused away into oblivion. Images can lose their substance, becoming Platonic shadows on the cave wall, but they retain their mesmerizing qualities. In the process, fascination can lead to forgetting. The invocation at the end reestablishes the beloved “you,” even substantially, yet it implies the existence of a “force field” — to borrow Agamben’s useful expression — of amorous tension engaging both lucidity and longing, realism and idealism.

In a state of amorous apartness, such are the intricacies of love — and Cavalli is at her poetic best when she evokes this topic. Her distich pinpoints an all-too-real ambivalence. To state the matter analogously, consider the English expression “absence makes the heart grow fonder” as coexisting with the Italian expression “far from the eyes, far from the heart.” Are not these two contradictory possibilities in fact often equally at work in us when we, ensconced in our solitude, love someone from afar? It follows that we can think of and at the very same moment forget our distant lover.

Cavalli’s love poetry, which formulates such complex psychological realities in limpid everyday language, often gives pause like this. Her verse is also sensual in refined ways. To wit, this untitled poem rendered by Geoffrey Brock:

But first we must free ourselves

from the strict stinginess that produces us,

that produces me on this chair

in the corner of a café

awaiting with the ardor of a clerk

the very moment in which

the small blue flames of the eyes

across from me, eyes familiar

with risk, will, having taken aim,

lay claim to a blush

from my face. Which blush they will obtain.

Cavalli not only captures an intense moment of encounter, but also offers a suggestive glimpse at the active as well as the passive aspects of the self in a state of desire. Her imagery is vivid, yet it incites the reader to think about it more abstractly as well. Equally memorable is another bar scene, as translated by J. D. McClatchy:

Very simple love that believes in words,

since I cannot do what I want to do,

can neither hug nor kiss you,

my pleasure lies in my words

and when I can I speak to you of love.

So, sitting with a drink in front of me,

the place filled with people,

if your forehead quickly creases

in the heart of the moment I speak too loudly

and you never say don’t be so loud,

let them think whatever they want

I draw closer melting with languor

and you eyes are so sweetly veiled

I don’t reach for you, no, not even the softest touch

but in your body I feel I am swimming,

and the couch in the bar’s lounge

when we get up looks like an unmade bed.

Time and again, Cavalli creates a deft, sometimes ironic, self-portrait. As she studies the self, that is to say “herself,” she simultaneously raises the issue of the beloved Other’s impact on the self. She ponders selflessness or, more specifically, an inclination to “de-self” or to be “de-selfed,” as one might call it. One of her poems concludes with the wish to be “free of being [herself].” In a three-liner rendered by Gini Alhadeff, she admits to a kind of inner emptiness, but the tone is serene and relaxed:

O loves—true or false

be loves, move happily

in the void I offer you.

If Cavalli’s poetry is egocentric, even probably autobiographical, its narrator shows a detachment enabling her to observe herself from one remove, even when she describes herself in the élans of attraction.

What Alhadeff’s Introduction does not state, and what no translator here reveals in poems which are addressed to a “you” and in which a mere suffix — an “a” instead of an “o” — specifies the “you’s” gender, is that Cavalli’s love poetry is implicitly and at times explicitly lesbian in orientation. In English, only context can sexualize the second person singular, whereas Italian grammar reveals gender in, for example, the suffix of an adjective or a past participle that qualifies a subject. In an untitled poem that begins “Love not mine not yours, / but the fenced-in field that we entered / from which you soon moved out,” the protagonist who has “soon moved out” is necessarily a woman because of the “a” in the “riuscita” of “poco dopo sei riuscita.”

As in C. P. Cavafy’s Greek verse, which some of these love poems recall, Cavalli rarely uses grammatical markers in this specific unambiguous manner — at least in the pieces chosen for this American selection. A reader coming across a poem such as the one just cited might make him or her wish to reread, differently, Cavalli’s love poetry.

But to what extent does one reread “differently” and is such refocus necessary? The contents of these poems are much less marked by homosexuality per se than by the poet’s distillation of essential elements of any human love, whatever the form: the characteristic signs and gestures of attraction, affection, attachment (or dis-attachment), and sexual desire. As in the verse of the Italian poet Sandro Penna, to mention an additional model, Cavalli’s verse exists at a level on which amorously connoted particulars evoke universal situations and states of mind. One also thinks of the Greek poet Dinos Christianopoulos, but his short, sometimes similarly aphoristic, erotic verse is harsher, more biting. Cavalli, who has also written an exceptional long-poem, “The Keeper,” has a gentler touch, is engagingly self-reflective, and even droll.

Poet Patrizia Cavalli — she distills the essential elements of any human love, whatever the form: the characteristic signs and gestures of attraction, affection, attachment (or dis-attachment), and sexual desire.

This book has been edited and introduced by Alhadeff, who has also translated many of its poems. Other poems have been rendered by thirteen additional translators, sometimes working in tandem: the aforementioned Strand, Brock and McClatchy, as well as Judith Baumel, Moria Egan, Damiano Abeni, Jonathan Galassi, Jorie Graham, Kenneth Koch, David Shapiro, Susan Stewart, Bruenlla Antomarini, and Rosanna Warren.

Graham’s translation philosophy differs markedly from that of her fellow translators. The other translators have produced fluid, accurate versions that formally resemble the originals; and some translated poems show discreet meters and rhymes that suggest those of the Italian poems. In contrast, Graham’s translations tend to be verbose in that she sometimes adds words or employs two or three words to render a single one in Italian.

Graham justifies her translation philosophy as follows. “[The poems] are not at all as simple to do as it seems,” she begins (as quoted by Alhadeff), “one wants to make them flow in this other language.” And she continues:

There is a rate of speed that English will render as almost a platitude. I have tried to retain the richness of multiple meanings over the speed of transfer. And Cavalli’s Italian is so effortlessly, naturally idiomatic, and idiom is clipped, whereas in American we would have to choose a specific idiom, and that risks sounding phony and betraying their easy universality of tone. So I am privileging voice and speed of image, and also, as much as possible, trying to replicate in some manner their sonic properties — even if it is with other sonic properties.

Graham errs here, despite her good intentions. “Richness of multiple meanings” is a key phrase, for it designates a problem that English-language translators often experience when faced with poetry written in a Romance language. To state the matter roughly: English is an exceedingly concrete language with lots of precise words, but more potential metaphorical or semantic resonance tends to inhabit a single Italian (French, etc.) word or phrase than its given English “equivalent.”

As a general rule, the translator of Romance languages seeks an English word that suggests some of this semantic resonance along with the primary meaning. This task is not always easy and is sometimes impossible. Yet the alternative — using two or three words in an attempt to cover much more of the semantic field of a single Italian word — involves the risk, not only of verbosity, but also of creating less resonance. This is no paradox in that English words, often so concrete in meaning, do not work together in the same fashion as do Italian words.

Let me give a few examples, from a single strophe of a single poem, from among the several other poems that Graham has translated according to her methodology. Cavalli begins one untitled poem from The Sky with these lines:

Quando si è colti all’improvviso da salute

lo sguardo non inciampa, no resta appiccicato,

ma lievemente si incanta sulle cose ferme

e sul fermento e le immagini sono risucchiate

e scivolano dentro

come nel gatto che socchiudendo gli occhi mi saluta.

With increasing wordiness, these lines are rendered by Graham as follows:

When one finds one’s self unexpectedly selected by health,

one’s gaze does not trip, won’t inadvertently stick,

but faintly wondrously grows attached

to hard matter, still matter, that leavening,

where images are swallowed up, where they slip down into one, easy,

as into this cat which clenches its eyes just now to greet me.

There is no question of one’s “self” in the original. And although this word, as well as “selected,” help Graham create some assonance with “health,” “selected” is actually rather abstract for the “caught” or “seized” that might more graphically have rendered the Italian original. “Lievemente” is translated as “faintly wondrously” and “cose ferme” becomes both “hard matter” and “still matter.”

Let’s dwell on “lievemente.” I would argue that “faintly” and “wondrously” are two separate notions, whereas the Italian word is a bundle of interconnected significations including “faintly” and “wondrously” perhaps, but also, more straightforwardly, “lightly” and especially “gently.” It occurs to me that this latter adverb, with its various connotations, provides some of that needed semantic resonance.

As to the last line, “just now” is not in the original and, moreover, is redundant since the verb “clenches” is in the present tense. In the line preceding that one, “le immagini sono risucchiate / e scivolano dentro” expands into “where images are swallowed up, where they slip down into one, easy.” Here, the “one” of “down into one” (the Italian “dentro” means “inside”) and “easy” are added by the translator.

Personally, this kind of translation practice is not to my liking. Perhaps other readers will appreciate Graham’s self-avowed attempt to produce an adequate colloquial idiom for what Italian readers admire in Cavalli’s own style. But to my ear, it’s the more sober versions made by the other translators that often capture the tone best. In any event, let me stop here, with these quibbles about a handful of translations in an otherwise welcome edition. This generous representative selection deserves many thoughtful readers, for who has not herself or himself been sometimes lost in what Cavalli calls “il buio dell’amore,” “the dark of love”?

John Taylor is the author of the three-volume essay collection Paths to Contemporary French Literature (2004, 2007, 2011) as well as Into the Heart of European Poetry (2008). He has recently translated works by Philippe Jaccottet, Pierre-Albert Jourdan, Louis Calaferte, and Jacques Dupin. He has just won the Raiziss-de Palchi Fellowship for his project to translate the Italian poet Lorenzo Calogero. His most recent collection of short prose is If Night is Falling (2012).

Tagged: Gini Alhadeff, Italian Poetry, My Poems Won’t Change the World: Selected Poems, Patrizia Cavalli

For such a distinguished translator, it is disappointing that Mr. Taylor resorts to linguistic absurdities such as the following: “English is an exceedingly concrete language with lots of precise words, but more potential metaphorical or semantic resonance tends to inhabit a single Italian (French, etc.) word or phrase than its given English “equivalent.” This doesn’t even make sense: find me a linguist who would support the notion of one language being more “concrete” than the other and I’ll give you a hundred bucks.

I maintain what I have written here—briefly, albeit, but I have expanded upon this perception in other essays about translating French poetry. I have also tried to show how William Carlos Williams’ maxim “no ideas but in things” could hardly win favor with most French poets, at least as a starting point for writing a poem. The ways in which poets form images is affected by lots of different factors, including the history of style, literary taste, and the evolving grammatical, syntactic, and lexical history of the language in question. The ways language is taught and style is “received” are also important. The French poet Yves Bonnefoy has written deeply on this question—the fundamental differences between English and French— in his essays about his own experiences as a translator of Shakespeare. Indeed, a good way of thinking about this question is to consider the centuries-old debate “Racine vs. Shakespeare.” What I am saying is that languages can have respectively different tendencies, informing perception and evocation, and that the translator must deal with them.

Hi, I was hoping you could quote the titles of the poem extract (the bar scene poem translation)