Fuse News Film Review: “The Gatekeepers” — Full of a Sense of History

By Harvey Blume.

Saw the Israeli documentary The Gatekeepers, finally. Had put off doing so because I thought I knew what to expect. But the movie (directed by Dror Moreh) was better, richer, than expected.

My views have long since been that Israel’s occupation of the West Bank is not just bad for the occupied but also for the occupiers. How nice, but how facile, for me, in the United States, to hold to such a fine and principled conclusion. It’s another thing entirely when four pillars of the Israeli defense establishment, four ex-chiefs of the Shin Bet, Israel’s major security organization, affirm the same thing, as they do, in this film.

All four have bloody hands, all have done what they felt necessary to protect Israeli lives. Israel is their country. It isn’t mine. I’m not an Israeli patriot. I’m an American Jew. These men had to make dire decisions about how to stop terrorists from planting bombs on buses in Tel Aviv, for instance, with horrific results the camera neither flees from nor dwells upon. In one case, these men had to decide how to neutralize, if that is the proper euphemism—not that the interviewees resort to euphemisms—a bomb-making genius under cover in Gaza. In one attempt to get at this engineer of havoc, innocents, including children, were killed. There had been faulty intelligence and too much ordinance. In another attempt, there had been too little ordinance, and the savant escaped.

The movie is full of a sense of history. It brings you back to the great gasp of hope occasioned by the Oslo Accords—that unforeseen handshake between Yitzhak Rabin and Yasser Arafat. As per those accords, Rabin acknowledged the right of the Palestinian people to a state of their own. This was an entirely new avowal to come from an Israeli leader. Arafat, at least formally, foreswore terrorism, an equally original idea for a Palestinian movement that had seemed bereft of any other thought.

Rabin is seen by these masters of Israeli security as the exemplary figure and is mourned as such by the retired elders of the Shin Bet. Rabin was the prime minister who pledged to pursue the peace process as if there were no terrorism and to combat terrorism as if there were no peace process. It’s bracing to recall that at the time there was an active, plausible peace process, as distinct from the increasingly wistful and forlorn references to such now.

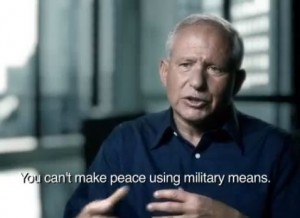

Ruminating on his career, one of the principles interviewed in this film says, “The Palestinians wanted a state. We gave them settlements. We wanted security. They gave us terrorism.”

That anti-peace dialectic continues.

For me, the most memorable, most frightening parts of the film have to do not with the bus bombings or other results of terror but with the massive, crazed Israeli demonstrations against Rabin, equating him with Hitler for coming to an accord with Arafat. Israel has genuine enemies without, to be sure. But The Gatekeepers leaves the impression that it has no less mortal an enemy within, a rabbinic establishment that furnished Yigal Amir, Rabin’s assassin—and therefore, it can be argued, the chief assassin of the peace process—with his certainties and his ideas.