World Books Interview: Daddy Colossus

By Bill Marx

Sigmund Freud sets out a weirdly Brobdingnagian survival scenario for kids. Young children rely on their parents, dependent on the intimidating bounty and emotional whims of “adult” giants who could easily dish out too much smothering love or unconscious hostility.

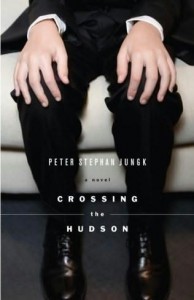

Novelist Peter Stephan Jungk weaves a playfully tragicomic variation on this primal generational dilemma in his fantastical “road trip” novel “Crossing the Hudson” (translated from the German by David Dollenmeyer, Other Press, 232 pages).

Author Peter Stephan Jungk” title=”psj-19408″ width=”300″ height=”200″ class=”size-medium wp-image-871″ />

Author Peter Stephan Jungk” title=”psj-19408″ width=”300″ height=”200″ class=”size-medium wp-image-871″ />Author Peter Stephan Jungk

The melancholic Gustav Rubin, with his virago of a mother, Rosa, in the car, becomes mired in an epic traffic jam on the Tappan Zee Bridge. The astonished pair spy the giant body of the deceased Rubin patriarch — the famed scientific genius Ludwig — stretched out on the Hudson River below.

Gustav’s confrontation with a corpse the size of a Macy’s Day Parade balloon (at one point, like a surreal mountain climber, he climbs up on the body) not only raises issues about the deep but haunting bond between a charismatic father and his bedeviled son, but explores the intricacies of mourning and the ambiguities of a Jewish family’s thorny past.

Jungk has written eight books in German, including the critically acclaimed biography “Franz Werfel: A Life in Prague.” Handsel Books has published English translations of two of his novels, “Tiger” and “Perfect American,” the latter, a fictionalized biography of the last years of Walt Disney, is being adapted into an opera by Philip Glass.

Via email I sent Jungk some questions about “Crossing the Hudson.” An admiring reviewer in the Times Literary Supplement suggested that the works of Franz Kafka and Philip Roth influenced Jungk’s tale of a giant Jewish father who won’t stay small or buried. I tossed in, for good measure, Donald Bartheleme’s study of bewildered sons confronting a bossy and undying dad, “The Dead Father.” As you can read below, Jungk sees this dadaesque dream as very much his own.

World Books: In what ways does the novel’s exploration of the complexities of the father/son bond build on ideas in your previous books?

Peter Stephan Jungk: It doesn’t

World Books: The novel’s surreal central image — the father’s giant body — suggests parable and parody. Is it one or the other?

Peter Stephan Jungk: It is always difficult for a writer to explore the reasons for his or her choice of images, ideas, situations. But I did feel – strongly even – that the image of the giant Father is a metaphor, a parable. Definitely not a parody! A clear metaphor for an overbearing, a powerful, famous, all-consuming father-figure. A father whose pride to be who he is surmounts that of his son by miles, by light years. He is “larger than life,” his intensity and his intelligence go far beyond his son’s capacities.

The image came to my mind one morning, 10 years after my own father’s death, lying awake one morning at 5 am … I saw the bridge, I saw the golem-like giant lying under it … and I knew I had to find out more about this strange image. And then one step lead to the next …

World Books: Donald Barthelme’s black comic novel “The Dead Father” features a grieving son who is left with “an inner voice commanding, haranguing, yes-ing and no-ing – yes no yes no yes no yes no, governing your every, your slightest movement, mental or physical. At what point do you become yourself?” Is this also the crux of Gustav’s predicament?

Peter Stephan Jungk: No

World Books: Did you set out to reexamine the images of Oedipal conflict presented by Jewish fathers and sons in Franz Kafka and Philip Roth?

Peter Stephan Jungk: No

World Books: What does the charged relationship between Gustav and his famous physicist father say about the gulf between those whose lives were directly touched by the Holocaust and their children?

Peter Stephan Jungk: I think many parents who lived through those terrible times preferred to spare their children the hardship(s) of being Jewish. They often downplayed or outright denied their Judaism, especially in Germany, Austria, and Poland. In the case of religious Jews it may be different, but the “free” ones tend to try to keep their children as untouched, as unfazed as possible.

In the case of Gustav and his father Ludwig, I guess that the son feels a longing for the roots of his forefathers. He even turns religious, keeping Shabbat, marrying a religious wife. His parents are quite shocked about this … their son going in the opposite direction they had chosen for him …

World Books: Please talk about the challenge of arriving at the novel’s tone, which combines the comic and the fearful.

Peter Stephan Jungk: Combining the comic and the fearful wasn’t something I planned or tried to achieve consciously. As so often in writing, an unidentifiable force takes over and decides what happens … decides what happens to the characters and decides what happens to the style. And to the writer himself …! I was rather surprised how funny the novel actually read in the end. This fascinates me most about the “art” of writing fiction: how the writer becomes a listener, a vessel for inspiration …

World Books: Why did you decide to set most of the novel during a traffic jam on the Tappan Zee Bridge? Why that bridge?

Peter Stephan Jungk: I feel bridges are close to our dreams. Especially bridges in the United States…they are so enormous, yet so appealing at the same time. The Tappan Zee seemed the right location for my novel since it’s the longest bridge spanning the Hudson…and because I know it so well, spending my summers not far away at a lake house, just like Gustav Rubin. But it’s not the lake mentioned in the book!

World Books: Jewish motherhood, in the form of Gustav’s hectoring mother and hysterical wife, doesn’t come off particularly well in the novel. Why?

Peter Stephan Jungk: Rosa, Gustav’s mother, just speaks the way she must. And so does Gustav’s slightly hysterical wife. I didn’t intentionally plan to denounce Jewish womanhood. But yes, I have personally suffered from the amazing powers and frightening manipulations of a Jewish mother …

Tagged: Crossing the Hudson, Featured, Other Press, Peter Stephan Jungk, book-reviews