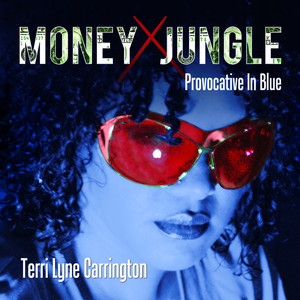

Fuse Jazz Review: Terri Lyne Carrington Takes on the “Money Jungle”

No one would say that Terri Lyne Carrington’s versions of Ellington’s pieces are definitive, but they extend the legendary composer’s legacy in a personal and significant way.

Terri Lyne Carrington’s Money Jungle: Provocative in Blue, featuring Gerald Clayton, piano. At the Berklee Performance Center, Boston, MA, February 14.

By Michael Ullman.

Drummer Terri Lyne Carrington’s concert on Thursday night was a celebration of her new disc, Money Jungle: Provocative in Blue (Concord Jazz). Her latest project (after her Grammy Award-winning disc, Mosaic) is a tribute to, as well as a redefinition of, a unique recording session made 50 years ago by Duke Ellington, bassist Charles Mingus, and drummer Max Roach.

The original Money Jungle was, according to Mingus, a stressful date. In his memoir Beneath the Underdog, Mingus talks about threatening to walk out of the studio. He told Ellington that he couldn’t play with “that drummer,” though he had, of course, performed with Max Roach dozens of times before. Ellington sweet-talked Mingus back into the room. The recording session continued and became known for, among other things, what it teaches us about Ellington’s capabilities as a solo pianist. And, of course, as another example of the way Ellington was able to get the best out of the different musical personalities he led.

During most of her concert at the Berklee Performance Center, Carrington projected on a screen a telling photo from the session: Ellington is seen playing at the piano while Max Roach hovers over him anxiously, looking as if trying to figure out what the older musician is doing. Meanwhile, behind them, apparently totally absorbed, Mingus is playing along, probably intuiting what Roach had to see for himself. The tension is palpable on the original recording.

The opening number of both discs, and of Carrington’s concert, was the title tune, “Money Jungle.” In the Ellington version, it begins with fierce strumming by Mingus, who is almost immediately joined, or perhaps opposed, by Roach, who enters full throttle. Ellington then plays a thunderous, dissonant chord that is the beginning of his theme. It’s a kind of harsh announcement as well as the first notes of the melody. “That’s the Negro’s life!” Ellington once said. “Dissonance is our way of life in America. We are something apart, yet an integral part.” Throughout the piece, its composer plays in a tart and jagged style, drawing on a fury few would ordinarily attribute to him.

Appropriately, in concert Carrington replaced Mingus’s part with a drum solo, mostly on tom-toms. Her melodic and yet driving style proves that she is a a worthy descendant of Roach. With a series of voice-overs about economic injustice (“People are basically just vehicles to create money”), she also made the political tension behind “Money Jungle” explicit. Ellington probably meant the tune as a comment on the commercial side of the music business, but Carrington’s desire to make a statement deviates from the practices of the always wary Ellington. In one of his relatively rare self-satisfied statements, Ellington said about his musical My People that “it was well done because we included everything we wanted to say without saying it.” Carrington says it, with quotations by Martin Luther King, Bill Clinton, and a crowd of others. Her goal, it would seem, was to educate the audience; she introduced a drum feature, for instance, with some information about Roach’s contributions to music.

Terri Lyne Carrington — a thinker as well as a stunning percussionist, an original even when she’s honoring others. Photo: Tracy Love

Performing with a band largely composed of able students, Carrington re-arranged the order of Ellington’s presentation and sometimes changed the tone of the music. (She didn’t play any of Ellington’s standards.) The amusingly titled “Backward Country Boy Blues,” which on the Ellington record begins with an improvised blues line by Mingus, started in concert with a recorded acoustic guitar and voice, over which vocalist Joanna Teters improvised hauntingly. The fast blues “Very Special,” another melodic line that sounds as if Ellington improvised it on the spot, was largely given over to pianist Gerald Clayton, who was also featured on his re-working of Ellington’s “Solitude,” here called “Cut Off.” Bassist Zach Brown had the unenviable job of playing Mingus’s parts. He held his own both soloing and in providing lines for the soloists, on the blues and on such playful, rhythmically complex numbers as “Wig Wise,” which Carrington somehow turned around mid-performance to pay tribute to Indian music in honor of the late Ravi Shankar. Carrington decorated “Rem Blues” with a poem by Ellington in which he compares music to, among other things, the woman you always wanted to find. I’m not sure the poem fit.

Still, Carrington has again proven herself a thinker as well as a stunning percussionist, an original even when she’s honoring others. Carrington has said that the music of Money Jungle haunted her for years. She is using it in Money Jungle: Provocative in Blue to make her own politically powerful, musically savvy statements. Clark Terry, whose recorded voice is heard on Carrington’s disc, said of Ellington that he “wants life and music to be in a state of becoming. He doesn’t even like to write definitive endings to a piece.” No one would say that Carrington’s versions of these pieces are definitive, but they extend Ellington’s legacy in a personal and significant way.