Book Review: Transformation Amid an Egypt in Decay — “The House of Jasmine”

By Roberta Silman

Though written in 1984, The House of Jasmine‘s description of widespread political corruption and social decay in the Sadat era is powerfully relevant to the uprisings of 2011, when Mubarak was ousted, and to those that are still roiling Egypt today.

The House of Jasmine by Ibrahim Abdel Meguid. Translated by Noha Radwan. Interlink Books, 168 pages, $15.

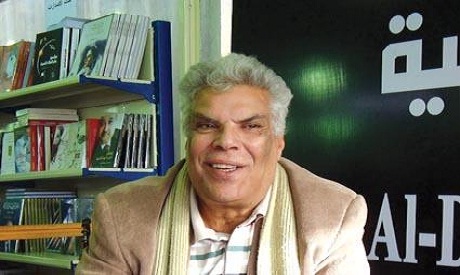

Ibrahim Abdel Medguid is a well-known, Egyptian writer, born in Alexandria in 1946 and winner of the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature in 1996. This interesting, short novel was actually published in Arabic in 1984. but is now being reprinted by Interlink Books in an excellent new translation by Noha Radwan, who has also written a very useful afterword. Indeed, I would recommend reading the afterword before getting into the novel.

Although we all know that nothing ever really changes, here is a fascinating confluence of events: this book, which describes the widespread political corruption and social decay of the Sadat era (1970–1981), is absolutely relevant to the uprisings of 2011 when Mubarak was ousted and to those that are still roiling Egypt today. However, what makes this novel so readable is not the politics but its narrator, Shagara, who works in an Alexandria shipyard and who tells his tale in such an appealing, intimate way.

There are echoes of Camus and Kafka and Beckett and even Jonathan Swift here, but Meguid has a distinct, somewhat quirky voice filled with humor and tenderness and an ability to pull the reader in. He also has a good eye for the absurd, so at times, particularly in the little vignettes that precede each chapter, we feel as if we are in a surreal painting. Yet, when you close this book you also realize that those sometimes hilarious vignettes helped illustrate what was happening in Egypt during the ’70s when nothing seemed to have a rational basis and the people were robbed of everything that they had gained under the socialism of Nasser.

The book begins when Shagara, a low-level worker who is utterly indifferent to politics, is recruited to take a number of workers to cheer at the motorcade for Presidents Nixon and Sadat in July of 1974. Instead of paying the workers the amount agreed to, he pays them half and pockets the rest. Moreover, he excuses them from their duty. So he is not only a thief but a moral bankrupt, someone who hasn’t even tried to fulfill his obligations to his boss. Shagara thinks he will be punished for this; instead, he is rewarded. Other demonstrations ensue, and soon he is as adept at working the system as his landlord, Abdul al-Fakahani, who has to be one of the most exasperating rascals in modern Egyptian fiction. And even when Shagara tries to confess to the three friends he has made in the cafe and who become his family after his mother dies,

. . . they only laughed. Maybe they were just trying to avoid hurting my feelings, but they kept laughing. They never criticized any of what I had done. I said that although I shared their laughter, I felt afraid every day when I went to work. At the very least, the chairman could force me to pay back what I had taken of the workers’ money. In that case, I would have no choice but to return the apartment to ‘Abdul al-Fakahani and become homeless.

Hassanayn said that people quickly forgot scandals, and Magid said that there might even be some people who secretly approved of what I have done.

Still, Shagara cannot be so accepting of his own flaws, and as he matures and the book progresses, he begins to look around him; on his walks to and from the city center, he passes a house that embodies all his dreams—a well-proportioned house surrounding a garden, filled with beautiful people who, though secretive, are clearly happy, cocooned by love. So he begins to realize that even in this city there may be the possibility of a life filled with more meaning than he imagined when he began working in the shipyard.

Novelist Ibrahim Abdel-Meguid — he has a distinct, somewhat quirky voice filled with humor and tenderness.

To someone whose image of Alexandria was based on the city as depicted in Lawrence Durrell’s famous Alexandria Quartet – a languorous, yet formal place filled with wealth and beauty and sex – The House of Jasmine presents a more modern, harsher, far more casual city, much more like the modern Egypt that is now being torn apart. Meguid gives us a real sense of its tattered state:

In winter, when raucous air flows down the roads, blowing paper scraps and screaming through the alleys, when the lights are turned off and you cannot tell the land from the sea, and the cafe becomes cold and wet, we all, without any prior agreement, refrain from going out. On the warmer nights we meet, also without any prior agreement. We go out at around the same time, and slowly walk down the side streets by the old walls, whose colors have faded. One of us may run into another, and we both smile, shake hands, and walk to the cafe together. Didn’t Hassanayn say that we all functioned according to a secret clock? This has become an established rule, and sometimes we manage to meet by chance at other times, too.

In the end, it is Hassanayn who helps Shagara attain some equilibrium, who finds him a wife and the deep connection of a happy marriage that can defy political troubles, even war.

In her afterword, Noha Radwan quotes Stendhal who “once wrote that ‘politics in the middle of things of the imagination is like a pistol shot in the middle of a concert.’” But, in this well-crafted, appealing novel, politics is given its proper place without “disrupting [the novel’s] harmony or detracting from its merit as a work of literature.” And that it remains so relevant, more than 25 years after its original publication, is even more testament to its value.

Roberta Silman is the author of Blood Relations, a story collection; three novels, Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again; and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. She writes regularly for The Arts Fuse and can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: Alexandra, Egypt, Ibrahim Abdel Meguid, Interlink Publishing, The House of Jasmine