Theater Review: Two Plays About Desperate People, Members of the 47%

The questions at stake are good ones and not asked very often in contemporary plays: why do some win and others lose in America? And what are the responsibilities of the haves and the have-nots?

Good People by David Lindsay-Abaire. Directed by Kate Whoriskey. Staged by the Huntington Theatre Company at the BU Theatre, Avenue of the Arts, Boston, MA, through October 14.

The Motherf**ker with the Hat by Stephen Adly Guirgis. Directed by David R. Gammons. Staged by SpeakEasy Stage Company at the Standford Calderwood Pavilion at the Boston Center for the Arts, through October 13.

By Bill Marx

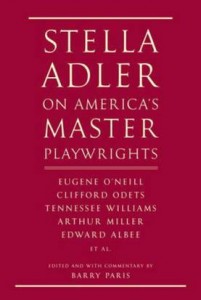

No Fun Being in the Underclass: Johanna Bay as Maggie in the Huntington Theatre Company’s production of GOOD PEOPLE. Photo: T Charles Erickson.

American Theater is usually well behind the times, its creators carefully calibrating rather than challenging popular taste, but the current economic free fall has been so hard for so long on so many that some companies seem to have caught up with the topic. The American Repertory Theater’s satire of the 1% via Marie Antoinette is too much of a lame cartoon to come off as more than a chic spectacle, but David Lindsay-Abaire’s Good People at the Huntington Theater Company and Stephen Adly Guirgis’ The Motherf**ker with a Hat at the Speakeasy Stage Company deal with the struggles of the working poor. And the latter are very much in the news, given that Republican Presidential Candidate Mitt Romney, via a leaked secret recording at a Florida fundraiser thrown to cultivate the well-to-do, proclaimed that 47% of the country does not pay income taxes, thus they are moochers and deadbeats. According to this upper class fantasia, members of the underclass believe themselves to be victims who are entitled to suck permanently on the teat of government support.

To their credit, both scripts, which are receiving fine productions, offer complex rejoinders to the bizarre notion that America’s supreme makers are being ripped off by lazy takers. Lindsay-Abaire and Guirgis generally stay safely away from salt-of-the-earth clichés with their inevitable suggestion that poverty is ennobling. (Still, as we will see, notions about lower class martyrdom have yet to be banished completely.) Neither play idealizes its down market characters or their conflicts; they both pivot (more or less) on the battle to find and keep a job when facing formidable internal as well as external challenges. Set in South Boston, Good People revolves around combustible issues of class warfare and self-image while The Motherf**ker with a Hat follows the efforts of the New York downtrodden to kick drug habits, false pride, and a life of crime. Both explore the lives of the working poor through the lens of dark (albeit often shading into sitcom) comedy, a farce-driven approach that is delightfully audience-friendly but that has its dramatic and political limits.

Good People limns the frazzled life of Margaret, a middle-age mother living in South Boston who, at the beginning of the play, loses her job at a Dollar Store because of habitual lateness, which is often caused by the demands of her mentally handicapped daughter. A high school flame, now a successful doctor, has come back to town, and Maggie figures he might have some sort of a position for her, or know of one. She ends up visiting the guy (who does not want his self-serving rewrites of his adolescent years in South Boston disturbed) and his black wife in their tony home in Chestnut Hill. The meeting leads to a powerful—if somewhat unconvincingly elongated—confrontation that dredges up volatile issues involving race, violence, class, paternity, and the benefits of community. The questions at stake are good ones and not asked very often in contemporary plays: why do some win and others lose in America? And what are the responsibilities of the haves and the have-nots?

Good People provides a vivid response to Romney’s charge that those who excel need thank only their own sturdy boot straps: it takes a village (or in this case a project) to foster individual success. Still, because Maggie restricts her opportunities to leave Southie in order to help another, Lindsay-Abaire turns the character into a sacrificial victim. She gives up on her chances for the good life so that others can succeed.

Bonding at Bingo: Nancy E. Carroll, Johanna Day, and Karen MacDonald in the Huntington Theatre Company’s production GOOD PEOPLE. Photo: T Charles Erickson.

At the same time, Lindsay-Abaire is too talented a dramatist to let Maggie and her friends, landlord Dottie and Jean, come off as working class angels. Intimations of self-hatred and manipulative gamesmanship infuse an undercurrent of bitterness into the hilarious interplay among Maggie, Jean, and Dottie. Of course, the tangy despair never comes close to taking center stage, and Huntington Theatre Company director Kate Whoriskey can’t be blamed for creating such a consistently funny production, given that she has at her command such expert comic actresses as Nancy E. Carroll (Dottie) and Karen MacDonald (Jean). (For the hometown crowd, the references to Boston locations and restaurants provide additional comic mileage.) Carroll’s aging narcissist, in particular, is molded out of a marvelous accumulation of idiosyncratic tics and inflections, droll facial and vocal details that are worth savoring.

As the upper-class couple, Rachael Holmes (the patient-to-the-max wife) and Michael Laurence (the doctor who escaped Southie) are at times pitched too high, drifting into counterpoised caricature. Johanna Day, as Maggie, plays the nimbly aggressive figure with skill; at times she supplies revealing signs of the elemental exhaustion and desperation that the robust laughs of the script and the staging keep at bay (much as the handicapped daughter is kept off-stage). It is that angst in the land of plenty, that vacuum at the heart of the hope that things will somehow get better, that Lindsay-Abaire (and other dramatists) need to face more directly, without one-liners and kitschy, homemade rabbit figures at the ready.

Evelyn Howe (Veronica) and Jaime Carrillo (Jackie) square off in THE SpeakEasy Stage Company’s production of THE MOTHERF**KER WITH THE HAT. Photo: Craig Bailey/Perspective Photo

As for The Motherf**ker with the Hat, I kept thinking about critic Richard Gilman’s line about David Mamet: “Tough talk is not the same as artistic vision.” Replace rough words with obscenity and the notion fits Guirgis’s script, whose frenzies of fornication/pissed off language is pungent, amusing, and at times exhilarating. My admiration for the verbiage is less about the acrobatic permutations it spins on rutting than how wryly the playwright lodges polyglot tidbits into the mix, including words such as ‘conniption.’ About midpoint the novelty of the torrent of curse-words wears off, leaving us with evaluating the dramatic conflict. Is there a point to this thin yarn of the relationship between a recent parolee, Jackie (a tamped-down Jaime Carrillo) and his AA sponsor, Ralph D. (a sharp Maurice Emmanuel Parent, who could exude more smooth, rascally charm). Jackie wants to play it mainstream, and is on his way with a new job and what he thinks is the support of a trustworthy guide until he spots a hat in the apartment of his drug-taking girl friend, Veronica (a fiery Evelyn Howe), and immediately suspects her of playing around. The guy loses his sobriety and stumbles into a series of embarrassing and/or revelatory confrontations, most memorably with Victoria, Ralph D’s disillusioned wife (a spot-on Melinda Lopez), learning, by the end, a valuable lesson in self-knowledge.

So there is something here beyond the off-color jokes, a minor study of the struggle for maturity (a theme in Good People as well—nobody in America seems to have become an adult) among an underclass mired in criminality and dependency. Here is it delivered by way of a retread Mametesque battle between a relative innocence and an American nihilism that, despite selling moral self-improvement, believes that everything is permitted. But as with Good People, The Motherf**ker With the Hat doesn’t take the proceedings too seriously, depending on broad characters, such as Jackie’s cousin Julio (an expertly clownish Alexjandro Simoes) to deliver easy laughs. Tragicomedy may be fashionable (especially on Cable TV), but these plays are content to accent the humor, as if they didn’t want to cause the audience too much upset given the troubling complexities of the social problems they touch on.

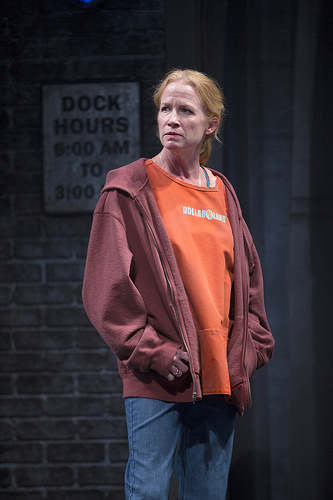

When I saw these plays I happened to have been reading the recently published Stella Adler on America’s Master Playwrights (Edited and with Commentary by Barry Paris, Knopf, 385 pages, $27.95), transcription of the legendary acting teacher’s talks on a number of major dramatists (Eugene O’Neill, Clifford Odets, Tennessee Williams, Arthur Miller, and Edward Albee). It put Guirgis and Lindsay-Abaire’s strengths and limitations into a bracing perspective. You don’t have to agree with her particular judgments (I am not a fan of The Skin of Our Teeth) to be inspired by the romantic ferocity and passion of her belief in the theater’s importance to the health of society: “I’m talking about real playwrights. I’m talking about plays that have in them enough to change the thinking of the world.” Today that iconoclastic mission has degenerated, far too often, into a dedication to conventional thinking, the goal to garner the next grant or win a slew of Tony Awards.

Adler knew Clifford Odets, and there is a chapter that includes her thoughts on how actors should tackle his scripts Waiting for Lefty and Golden Boy. I have never seen the former play, the struggle among union workers to decide to strike, though many critics snicker at the very mention of the title, which has come to signify fist-waving didacticism. (I saw a terrific production of Golden Boy at Trinity Rep, directed by Richard Jenkins, in 1990.) Her description of Waiting for Lefty suggests that it might be possible to write plays about income inequality, the plight of the underclass, and unions (an invisible subject in contemporary theater) in ways that don’t have to hug the rail of comedy for support.

“Every character in the play [Waiting for Lefty] is caught in some situation,” Adler writes. “The situation is forcing them to change the world. What does it mean to fight, to strike, to struggle through to victory? The other side needs to control, to manipulate, to hold you in place…. for the agent, as well as for the industrialists, who need to hold on to their money and authority. That’s the conflict. It’s not a conflict of individuals. It’s bigger.” Odets’s take may very well be antiquated (though it would be fun to see a good production), but aren’t the traumatic rifts in the world economy, the banking meltdown, the mammoth cases of corruption and the fat cat bail outs, the growing wave of strikes throughout Europe, and the political pressures on collective bargaining worth dramatizing in big and complex ways? Must our theater’s focus on the struggle for so many to make a decent living be so small and safe? Eugene O’Neill died before he could complete his epic about Americans as “Possessors Self-Dispossessed” — it is not too late.