Book Commentary/Review: Imagine There Are No Negative Reviews — It’s Not So Easy If You Try

Who has taken criticism out of the hands of the “true critics”? Is someone making me read rancid Amazon reader reviews? Where do we look for the “true critics”?

By Bill Marx

The current flap about the value of negative reviews has kicked up a surprising amount of dust at Salon, The Awl, and elsewhere (including The Arts Fuse), with just about everybody commenting on the fracas trying to scramble onto a plot of non-existent high ground. Daniel Mendelsohn’s A Critic’s Manifesto at the New Yorker blog proffers an admirably trenchant justification of negative reviews as an inevitable part of any serious conception of independent, intellectually responsible cultural criticism. For Mendelsohn, reviews are less about the judgments than they are an educative means to stimulate thought about the arts through the lively articulation of how the reviewers came to their verdicts. As the great dance critic Edwin Denby put it, “An intelligent reader learns from a critic not what to think about a piece but how to think about it: he finds a way he hadn’t thought of using.”

About the New Yorker critics he loved as an adolescent, Mendelsohn writes that “the example that they set, week after week, was to recreate on the page the drama of how they had arrived at their judgments. (The word critic, as I learned much later, comes from the Greek word for ‘judge.’)” From that elemental insight stems the rest of Mendelsohn’s solid argument, and his reference to dramatic tension within reviews is particularly apt. Critics pay homage to the love they have for the arts, and also serve an important cultural role, by asserting standards of discrimination. They do this by writing with expertise, sometimes in admiration, sometimes not, more often than not finding themselves having to calibrate between the two extremes. Revered Boston theater critic Arthur Friedman used to say that you know when a critic is burnt out when he or she only writes raves or pans—it takes time and patience to modulate between what works and what doesn’t. When the job has soured, making a judgment becomes the bottom line rather than triggering an obligation for detailed reaction and analysis.

I recommend Mendelsohn’s piece wholeheartedly, though I have a reservation that is worth making because I think this misstep undercuts the strengths of his clear-eyed description of first-rate criticism. He is right to see that the controversy about negative reviews is about more than the kerfuffle over a few recent put-downs in prominent mainstream publications:

The storm is a good thing: at no point since the invention of the printing press, perhaps, has the nature of literary culture, and the activities of its practitioners—authors, critics, publishers—been in such a state of flux. The flux is both fascinating and destabilizing, for those of us who grew up in the waning days of “old” literary culture, and the changes resulting from are it likely to be permanent and far-ranging

He is correct about the confusion, and the current debate should bring us back, as Mendelsohn’s piece does, to consider what arts criticism is supposed to be. What’s in flux is the definition of arts criticism, and that is under attack from a number of different quarters—marketing, technology, academia, and editorial. The problem isn’t just that the powers-that-be in these areas think that criticism should just be another form of publicity—that is an old, old threat. But that editors at major newspapers and magazines and in journalism schools don’t seem to know or care that the craft of criticism is rooted in the need to make a judgment backed up by reasons and analysis. The dumbing down of reviews into opinions, snark, YouTube screeds, etc, is across the board—frankly, it is not just in the “reviewers” pages at Amazon—but in the very august places (yes, even in The New Yorker), where genuine criticism of the arts should be protected and defended. If generations of readers don’t see “the real thing,” than the watered-down facsimile will become the unquestioned expectation.

The future of arts criticism is being shaped now — we need to look at the past to get an idea of what criticism at its finest has been. Mendelsohn does this when he talks about how inspiring it was for him as an adolescent following the superb critics in the New Yorker. But criticism goes beyond the precincts of The New Yorker and further back than Mendelsohn’s salad days. (Over a hundred years ago, Edgar Allan Poe, trying to make a living as a critic, was battling some of the same issues bedeviling criticism now, from anonymous reviews to free-falling editorial standards.) Here is where Mendelsohn doesn’t go far enough. Yes, critics must love the arts, but they must also care for and serve the craft of criticism. The wanna-bees on the Internet are only part of the debasement: fewer and fewer editors, journalism professors, and critics are familiar with what criticism should be. Let’s assert, with passion and know-how, what can be saved from “old literary culture,” rather than give up without a fight. When they saw arts criticism in crisis, reviewers from Poe to Henry James and Edmund Wilson found ways to bring the best of the past into the future.

Thus Mendelsohn’s wrap-up, somewhat congratulatory in tone, begs the question about the future of arts criticism his admirable manifesto raises:

I wonder whether the recent storm of discussion about criticism, the flurry of anxiety and debate about the proper place of positive and negative reviewing in the literary world, isn’t a by-product of the fact that criticism, in a way unimaginable even twenty years ago, has been taken out of the hands of the people who should be practicing it: true critics, people who, on the whole, know precisely how to wield a deadly zinger, and to what uses it is properly put.

Who has taken criticism out of the hands of the “true critics”? Is someone making me read Amazon comments? Where do we look for the “true critics”? Anyone can carefully study the writings of the arts critics that Mendelsohn adores and then take a crack at writing thoughtful reviews. Arts criticism is not an aristocratic enterprise, reserved to those few who are born with the proper taste and intellect. There is something resolutely, delightfully democratic about criticism—whoever can write the most stylish, most convincing, most analytical review meets the exacting standards of the craft. Some excel at articulating the reasons behind their aesthetic responses, others do not.

The truth is, those selected to pick the critical gatekeepers (editors and publishers) are pretty much at fault for the current “flurry of anxiety and debate” because they will not or cannot discern the difference between arts criticism done poorly and criticism done right. The problem that Mendelsohn, perhaps for diplomatic reasons, ignores is that the standards for arts criticism (which have always been in flux) have become debased all along the line, online and off. Frankly, criticism has far more to fear from its supposed friends than its easy-to-identify enemies.

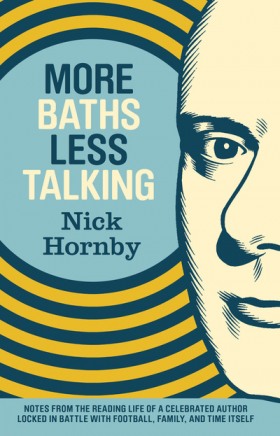

What would a literary world without critical pans be like? “Imagine there are no negative book reviews,” sings John Lennon. “It’s easy if you try.” Well, maybe it’s not that easy. Editors at the Believer magazine are on a self-proclaimed mission do away with discouraging words about contemporary books and authors, and they have enlisted novelist Nick Hornby to play nice in his monthly column “Stuff I’ve been Reading.” The third gathering of these monthly pieces, More Baths Less Talking, suggests that Hornby wants to cooperate, but to his credit he chafes at the zinger ban. After quoting a put down from New Yorker critic Robert Benchley, Hornby sighs: “You are not allowed to write cruel lines like that in this magazine, which is the only reason why I don’t.” Please, Believer, let Hornby get down and dirty. When it comes to literary criticism, cleanliness isn’t necessarily next to godliness—it tends to rub shoulders with the sanctimonious.

In that sense, the book provides indirect but powerful proof of Mendelsohn’s contention that the critic shows his love for the arts by venturing beyond making recommendations but by providing the theatrics, emotional and analytical, behind his verdicts. By justifying their fault-finding and praise, critics both establish credibility with readers and stimulate meaningful talk about the arts. Hornby is a best-selling novelist, but that doesn’t automatically make him a first rate critic—he has to persuade me with his reasoning and evidence. More Baths Less Talking convinces me that Hornby is an entertainingly opinionated member of the chattering classes, lacing his usually solid book selections with personal anecdotes, questionable generalizations, self-deprecating jokes, and occasional insights into the film and book circles he frequents.

Each column for the month includes a list of books Hornby bought and those he read. His tone about the volumes he cherry picks is generally comic and casual, his focus on triumphant new books (a lot of non-fiction this time around, which he remarks on), and he swerves, sometimes too easily, into talking about his domestic life and/or current projects, which includes writing a screenplay for Colm Tóibín’s novel Brooklyn. Along the way, he makes a compelling argument for reading short rather than long books, discovers Muriel Spark (I envy him the delight of reading her Memento Mori for the first time) and admits that now, in his early fifties, he has “discovered that some of the old shit isn’t so bad.” He has always been an admirer of Dickens and Shakespeare and stimulated by his enthusiasm for Sarah Bakewell’s superb book on Montaigne, he shows some grudging signs of affection for the French classic. Some other books that Hornby gives a blurb-ready thumbs up: Austerity Britain (“a major work of social history: readable, brilliantly researched, informative, and gripping”), his friend Sarah Vowell’s Unfamiliar Fishes, his brother-in-law’s novel The Fear Index, and Nicholson Baker’s The Anthologist (“It’s a wonderful novel, I think, unusual, generous, educational, funny”).

There is an appetite for this kind of easy, breezy, log-rolling writing about books, punctuated by polemical shout-outs about reading for pleasure rather than as a duty. Hornby has critical fans at Salon, NPR, and The Guardian, and anything that brings comic pizazz to spreading the word about reading good books should be encouraged. At times the column’s punch lines are canned—why would Hornby take a 1976 John Updike novel (Marry Me: A Romance) about the pains of matrimony off the shelf unless he’s planning to use it to generate Henny Youngman laugh lines comparing the sex antics in the book with what goes on (and doesn’t) in the Hornby bedroom. But despite the transparent set-ups, More Baths Less Talking provides plenty of pointed, if at times self-serving, fun.

The critical component of Hornby’s performance, however, suffers from laziness, and not only because he has been ordered to only write about books he likes. He occasionally emits the kind of grumpy or bubble-headed pronouncements of a popular writer who, after a few too many drinks, wants to blow off steam. Here are a few of the gusts:

. . . those who invest heavily in cultural capital don’t like art that can’t exclude: it’s confusing, and it doesn’t help us to meet attractive people of the opposite sex who think the same way we do.

As we know around these parts, only Great Literature can save your soul, which is why all English professors are morally impeachable human beings, completely free from vanity, envy, sloth, lust, and so on.

And did you know that the whole highbrow/lowbrow thing came from nineteenth century phrenology and has racist connotations?

Great writing is going on all around us, always has done, always will.

Take away the historical fiction, and the genre fiction, and the postmodern fiction, and the self-important attention-seeking fiction, and there really isn’t an awful lot left.

Great writing is rare, so it is not very difficult to come up with plenty of “lost” decades—any great American plays before the scripts of Eugene O’Neill? Surely we are beyond the moldy, cartoon battles of the common reader versus the elitist eggheads? You can argue for the pleasures of reading without conjuring up pointy-headed straw men, the killjoys of yore out to squash the wide-eyed party of the vox populi. Books need all the champions they can get—why turn anyone away from reading what they find satisfying?

When it comes to aesthetic standards, Hornby is all over the map, sometimes arguing for a complete acceptance of the market-driven virtues of the monoculture—read and let read, different strokes for different folks, let a thousand volumes bloom in the bookstores, and so on. But if that is true, than who are those mangy postmodernists and genre writers that aren’t worth bothering with? Name names. Some critics argue that Tóibín produces the kind of “self-important attention-getting” fiction that Hornby dislikes.

Of course, there are plenty of bad, overpraised books out there, but aren’t they outside the perimeters of the column? Sweeping negative potshots are presumably off-limits as well, unless Hornby is willing to roll up his sleeves, do the work of a genuine critic, and explain why these authors are mediocre. Editors of the Believer take note—your man is in danger of going off the happy talk reservation.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of the Arts Fuse. For just over four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: A Critic's Manifesto, Daniel Mendelsohn, More Baths Less Talking

Yes. A “comic and casual” tone is right for 99% of what’s written, but it will fail utterly with real literature.

I agree with what Bill Marx says 100%. I reject the use of Daniel Mendelsohn as a model. He represents erudition without wisdom. I will never forget the revolting exchange between Mendelsohn and Tom Stoppard over “The Invention of Love” in the New York Review. Mendelsohn went way beyond criticism of the play or the performance and presumed to tell Stoppard how he should have written the play. He told Stoppard that the playwright misunderstood his own play. With each new response Mendelsohn’s overreaching and self-serving self-love became more apparent. The fawning over him by certain older academics suggests more the cup of Ganymede being passed than a torch. Mendelsohn’s arrogance, redundancy, and self-absorption are abhorrent. I am so disturbed by his critical narcissism that I freely admit the impossibility of objectivity. For a balanced assessment of his limitations see, https://forward.com/culture/432863/the-classical-trouble-with-daniel-mendelsohn/