Classical CD Review: Groundbreaking Bach on the Mandolin

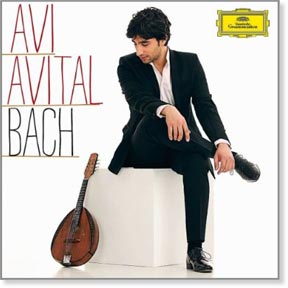

Avi Avital, a young virtuoso determined to expand the repertoire, is the first mandolinist ever to be signed to a contract with Deutsche Grammophone. His recording of Bach for the label is an important milestone for the mandolin.

By Jim Dalton

In the program notes for his debut CD for Deutsche Grammophone, simply entitled Bach, Grammy-nominated mandolinist Avi Avital discusses the ways he challenges his instrument. At one point, he explains that “Bach’s music is full of secrets . . . Using a different instrument allows you to hear its timelessness in a new way.” For this ambitious project, he chose to record four works that Bach composed for other instruments.

Bach, unlike Vivaldi and Handel, never wrote for the mandolin, either solo or in ensembles. Though other mandolinists have performed transcriptions of the Sonatas and Partitas (originally for solo violin), or of the Cello Suites (also solo), few have ventured beyond these compositions. Avital, however, gives us exquisite and idiomatic transcriptions of three concerti (two originally for harpsichord, one for violin) and a sonata (originally for flute) on this album.

The difficulty of transcription lies in producing a version of the piece that sounds effective in its new medium. Ideally, the listeners should lose themselves in the music, oblivious of its origins. Avital accomplishes this, both through his skill as a transcriber and with the sheer musicality of his interpretations.

Avital’s playing proffers a wide range of dynamics and tone that he modulates in an arresting manner. His tone is generally slightly darker than Italian players—though he studied in Italy with Ugo Orlandi. This is partly because of his choice of instruments. The Italians (and most other European mandolinists) play on bowlback mandolins that have a slight cant to the top. Avital’s beautiful instrument, made by Israeli luthier Arik Kerman, has a flat back and top.

For the concerti, the tone of the mandolin blends well with the ensemble in the ritornelli and other tutti passages. It offers just enough of a different timbre and articulation to color these passages without dominating them. In the solo passages he brings the mandolin to the fore without sounding forced.

In the two concerti originally for harpsichord (BWV 1052r and BWV 1056r), the quick decay of the plucked tones of the mandolin naturally resembles the tones of a harpsichord, making these a natural choice for transcription. In the first movement of the D minor concerto (BWV 1052r), there are passages involving repeated pitches (“a” and then “d”) that, when using open strings for those pitches, creates typically idiomatic mandolin phrasing. This type of passage work is also common in Bach’s violin works. (The two instruments share a common tuning.) This may be why some scholars believe the work to be based on a now-lost violin concerto.

Those who only have a passing acquaintance with the mandolin may be struck by the absence of tremolo (rapidly repeating tones played by alternating up-and-down strokes) to simulate long tones. Paul Sparks, a specialist in historical mandolin technique, calls it “the most contentious aspect of mandolin technique . . . . Some regard it as the very soul of the instrument, others as an annoying affectation that prevents the mandolin being taken more seriously by the musical establishment at large.”

Though Avital has, in other performances, used a ravishing tremolo with great control of timbre and dynamics, here he chooses to rely on the natural sustain of the instrument, stylish ornamentation, and on a stunning sense of phrasing, which renders the question of tremolo moot—even on the transcriptions from flute and violin. In fact, the slow movements provide some of the high points of the album. Listen to the well-known Largo of the G minor concerto to experience what effective transcription should be. Between Avital’s lyrical phrasing and his seamless transcriptions, you can easily forget about the harpsichord and oboe versions that you’ve heard before. You start to believe it was originally written for the mandolin.

In the popular Violin Concerto in A minor (BWV 1041), Avital’s impressive technique makes the 32nd-note passages, normally taken in one bow by violinists, seem perfectly phrased—even though each note is individually plucked with the plectrum.

The orchestra for the concerti is Kammerakademie Potsdam with Shalev Ad-El at the harpsichord. The orchestral sound is magnificent throughout, and the interpretations, though not in the purest sense “authentic” (Avital’s mandolin is not a period-style instrument), are informed by a deep knowledge of performance practice. Balance between soloist and ensemble is good overall, and the quality of the recorded sound is up to DG’s usual high standard.

Avi Avital—his playing proffers a wide range of dynamics and tone which he modulates in an arresting manner.

The Sonata in E minor (BWV 1034), originally for flute and continuo, provides a pleasant contrast to the virtuosity of the concerti. It demands a more intimate sound, and this mellowness is enhanced by the excellent choice of theorbo and cello for the continuo, played by Ophira Zakai and Ira Givol, respectively. Zakai’s theorbo provides a lighter touch to the proceedings than a harpsichord would, and this enables Avital to phrase more delicately than he does in the concerti.

For me, one of the high points of the entire program is the third movement (Andante) of the sonata. The use of pizzicato cello and the sensitivity of the three players to each other sets a mood that perfectly contrasts and complements the rest of the sonata.

The four pieces represented in this album are excellent additions to the repertoire. Avital proves to be a fine interpreter of Bach, the instrumentalist’s sensitivity to the timelessness of the composer’s music evidence of a strong sense of “the long line.”

© 2012 Jim Dalton

Jim, I very much appreciate the way you explain how the physical attributes of his instrument and technique create and sustain Avi Avital’s musical decisions. Bach’s compositions, as you know, were often repurposed for other instruments in his own day, and have been passed around in transcription for new or unexpected instrumentation ever since.

DG has uploaded one Youtube promo, that has him speaking over most of the music, which is frustrating (albeit he seems like a charming fellow) and the footage of him playing the Bach Concerto in A Minor in Milano in 2009 is somewhat overwhelmed by the orchestra in this amateur footage, probably taken with a cell phone.