Book Review: “Second Person Singular”—A Powerful Look at Israel’s Tangled Issues of Identity

In his novel, Sayed Kashua paints such a vivid picture of modern Jerusalem that I found myself longing to see that city again; he also portrays a whole spectrum of Arab life in Israel—from the poor families visited by the social workers to the ambitious Arab mothers and their sometimes feckless sons—with empathy and humor.

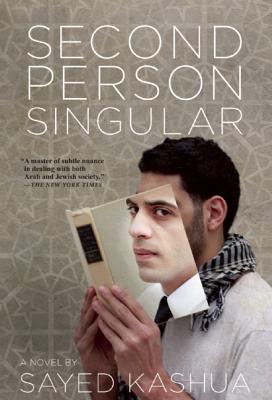

Second Person Singular by Sayed Kashua. Translated from the Hebrew by Mitch Ginsburg. Grove Press, 352 pages, $25.

By Roberta Silman

I had never heard of Sayed Kashua, but I was immediately interested when I learned that he is a young Palestinian, born in 1975, who writes in Hebrew. There’s an interesting identity for a modern writer, I thought, and wanted to know more. And since Second Person Singular was originally published in Hebrew in 2010 and is only now published in English—in a strong and accessible translation by Mitch Ginsburg—there was plenty of information about Kashua on the Web. He is the author of two previous novels that have received several prestigious prizes, but critics feel that this new one is his best. He is also the creator of a popular, Israeli sitcom called Arab Labor.

Second Person Singular is many things: a psychological mystery reminiscent of Nabokov; a touching examination of what it means to be Arab in a Jewish state, where, to the average American reader, identities would seem to be unalterably fixed and where no Arab would ever want to be mistaken for a Jew; a family comedy that involves all sorts of delusions and secrets and lies; a family tragedy about a young, paralyzed, Jewish man; and, finally, a triumphant escape from one identity into another.

What makes this book so appealing is that its serious themes sneak up on the reader. It begins with a look into the life of a classic nouveau riche identified only as “the lawyer,” who has a social worker wife, Leila, and two children, who is so persistent in his desire to play the part of the successful Arab in Jerusalem that he becomes a comic universal figure, emphasized by his lack of name, a la Gogol. He sleeps alone in his daughter’s room on a mattress plopped onto a Winnie The Pooh rug, surrounded by the stuffed animals and pink accessories normal to a six-year-old girl; his wife sleeps in their queen bed with his daughter within reaching distance of the newborn baby boy’s crib. He and his wife “visit” each other regularly, but no one in his right mind would ever say that this is a particularly affectionate or passionate marriage. But the lawyer is, with all his flaws and concern for appearances, an affecting character. Here he is thinking about his children:

After all, the decision. . . to send off their children to study with Jews, the lawyer thought, was not borne of shared ideals or a dedication to coexistence, as the brochures claimed and the philanthropists believed; the Arab parents simple wanted their children to soak up Western culture, for their children to learn from the Jews that which they themselves could not provide. All of a sudden the lawyer started to feel that they were sending their children like spies into the heart of a foreign culture. It will be interesting to see what type of insights they come back with, the thought, whether they return as double agents.

So you find yourself rooting for him even when he is most intent on paying for all the things he thinks he needs—like his Mercedes-Benz—and not shaming his wife when they go to their monthly meetings of their book club. The book club is key, because when he goes to his favorite bookstore and buys a second-hand copy of Tolstoy’s The Kreutzer Sonata in an effort to impress his friends and wife, the most terrible time in the lawyer’s life begins.

After the hilarious meeting of the book club, the lawyer leafs through the novel that he is, of course, too tired to read, when a note drops out, written in Arabic in what he is convinced is his wife’s hand: “I waited for you, but you didn’t come. I hope everything’s all right. I wanted to thank you for last night. It was wonderful. Call me tomorrow?” And at the end of that part, he finds the name of the previous owner “written in a thin, delicate hand, in blue ink: Yonatan.” Thus begins his almost picaresque search for Yonatan that leads to murderous feelings for his wife because he is absolutely convinced she is having an affair, their misunderstandings when they do come together, and his fevered musings about his own sexual naivete, their short courtship, and marriage. Here is an example of how jangled his thoughts have become:

Only now, for the first time in his life, did he understand what honor meant. He, who spoke out against and even lectured now and again about honor killings, he, who opposed the phenomenon and labeled it barbaric, only now saw the error of his ways. He wished someone from her family would kill her. But who would do it? Which of her brothers would risk arrest and a life of destitution for his children? He wished she was dead. But what about the kids, he wondered, and his heart broke at the thought of them mourning for their mother.

Because Kashua is an unusually ambitious and gifted writer, his creation of the “second story” in which Yonatan becomes the linchpin of the novel yields surprising and touching results. Yonatan becomes not only a clue to the lawyer’s search but also key to another story about an Arab in Jerusalem—this time a poor social worker, named Amir, who is 28 years old and is now Yonatan’s caretaker. Unlike the lawyer, who is obviously at the mercy of Kashua’s talent for satire, Amir tells his own story in the first person: How he left his small, Arab village where he had somehow been cheated out of his father’s land, how he came to Jerusalem to be educated, how he found his first flat and job and had a fleeting attraction for a woman, how he became the caretaker of a young, Jewish man, Yonatan, who is unable to move or speak, and, most amazing, how he became interested in Yonatan’s photographic equipment and befriended Yonatan’s mother, Ruchaleh.

Sayed Kashua — his exploration of the complexity of identity in Israel makes his novel remarkable. Photo: Dan Porges

It would be unfair to give away the second half of this book, which is as intricately wrought as a difficult jigsaw puzzle, and although I didn’t believe in every last detail, I wanted to see how all this chaos would somehow be resolved. As important as the plot is the setting. Kashua paints such a vivid picture of modern Jerusalem that I found myself longing to see that city again; he also portrays a whole spectrum of Arab life in Israel—from the poor families visited by the social workers to the ambitious Arab mothers and their sometimes feckless sons—with empathy and humor.

But it is the theme of identity that makes this novel so outstanding. Despite its light touch, this novel gets to the heart of that matter. And what Amir manages to do with his own identity is remarkable and will surely provoke discussions in lots of book clubs for years to come. After I closed Second Person Singular, I went back to Cynthia Ozick’s essay about Isaac Babel and found a passage I had marked in Fame & Folly:

It may be that the habit of impersonation, the habit of deception, the habit of the mask, will in the end lead a man to become what he impersonates. Or it may be that the force of ‘I am an outsider’ overwhelms the secret gratification of having got rid of a fixed identity.

It is clear that Kashua is struggling with these questions. That he has created such a complicated and fascinating piece of fiction as part of that struggle should not only give comfort to all of us who are concerned about the fate of Israel but provides reassurance that the imagination can find possibilities for understanding in what appears to be the most intractable conflicts.

Roberta Silman is the author of Blood Relations, a story collection; three novels, Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again; and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. She writes regular for The Arts Fuse and can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: fiction-in-translation, Hebrew, Mitch Ginsburg, Sayed Kashua