Concert Review: Concord Chamber Players and Jessica Zhou

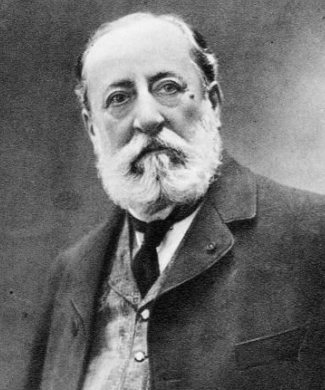

In a nice twist, no piece on the Concord Chamber Players program was written before 1907, and that oldest piece came from a fine composer, Camille Saint-Saëns, whose music has fallen somewhat by the wayside since his death in 1922.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

What do a bitterly cold winter’s day, professional football, and 20th-(and 21st-) century, classical music have in common? Well, on the surface, not much. But last Sunday afternoon, a large and enthusiastic audience braved the Arctic chill to hear a thoughtfully varied program by the Concord Chamber Players (CCP) and harpist Jessica Zhou at the Concord Academy Performing Arts Center.

For more than a few of us, this concert no doubt presented a nice respite from some intensely exciting playoff action over the weekend. For the afternoon’s performers, nearly all of whom are drawn from the Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO), this was another gig in the midst of a very busy season. If they are feeling any fatigue at this point, it surely didn’t come across in the involved, convincing playing we heard on Sunday.

In a nice twist, no piece on the program was written before 1907, and that oldest piece came from a fine composer, Camille Saint-Saëns, whose music has fallen somewhat by the wayside since his death in 1922. Filling out the program were scores by Mikhail Mchedelov and pieces by two composers with long BSO associations: Andre Previn and John Williams.

Though in recent years Mr. Previn’s cut a rather frail figure on the podium (he turns 83 in April), he has remained a very active composer and the Clarinet Sonata on Sunday’s program dates from 2010. To these ears, Previn the Composer has often been something of a mixed bag. At his best (which, admittedly, is awfully good), he can turn out a hauntingly beautiful tune or a wildly energetic riff—his “Vocalise” and the aria “I Can Smell the Sea Air” (from A Streetcar Named Desire) are terrific examples of the former, while the closing “Dance” from Tango, Song, and Dance amply demonstrates the latter quality. At his less inspired, though, he tends to be little more than a competent note-smith who churns out page after page of active but ultimately forgettable material.

I’m happy to report that I found the Clarinet Sonata to fall decisively in the former category: it’s thoroughly ingratiating. Written in four movements (the fast, outer ones bracketing two slow ones), it breaks no new musical ground, but it retreads the hallmarks of Mr. Previn’s distinct style in continually fresh ways. The brisk opening movement sounds something like a cross between Prokofiev and Leonard Bernstein, with jagged, syncopated rhythms that morph into long-breathed, lyrical melodies. The first slow movement (marked “Very Slow”) opens with a beautiful clarinet melody that is reprised later on in the instrument’s chalumeau register to fine effect before dissipating in an enigmatic flourish. The brief, second slow movement (which Mr. Previn calls an “Interlude”) features a repeated clarinet riff whose piano accompaniment grows into an increasingly elaborate, pseudo-gospel hymn before it breaks into fragments at the end. In the finale, mixed meters and rhythmic hi-jinks prevail in a thoroughly characterful movement that ends the work in high spirits.

On Sunday clarinetist Thomas Martin, the work’s dedicatee, navigated the Sonata’s twists and turns with dexterity and feeling. Pianist Vytas J. Baksys made an ideal accompanist, never overshadowing the solo clarinet, but all the while clearly enunciating Mr. Previn’s active piano writing. Together, they gave about as definitive a performance of the piece as one could want and made a strong case for its inclusion in the repertoire.

Camille Saint-Saëns is a wholly underrated composer: as a melodist he ranks with Faure, Chausson, and Hahn; as an orchestrator he could be as inventive as Liszt.

Following the Previn, BSO principal harp Jessica Zhou and violinist Wendy Putnam (also of the BSO and director of the Concord Chamber Music Society) presented an equally strong case for the Saint-Saëns Fantasie for Violin and Harp (op. 124). I’m sure there are plenty of people who disagree with me, but I’ve always felt that Saint-Saëns is a wholly underrated composer: as a melodist he ranks with Faure, Chausson, and Hahn; as an orchestrator he could be as inventive as Liszt; and as a musical technician, he leaves very little to be desired. So what if pieces like this Fantasie are tuneful showcases of instrumental virtuosity? What’s wrong with that? I can think of plenty of pieces that aim higher and fall flatter, but now I’m starting to digress.

The present Fantasie was dedicated to (and, presumably, written for) Marianne and Clara Eisler and falls into one extended movement divided into several characteristic sections. Ms. Putnam and Ms. Zhou were perfectly at home in the style of the music, which is generally driven by a strong, lyrical impulse. They blended to particularly fine effect in a passage of violin pizzicato (plucked strings) paired with harp harmonics: both performers seemed to create a new instrument, the violin-harp (or harp-violin).

My only complaint about the performance was that I felt that Ms. Putnam could have made more of the big violin moments—it sounded like she was holding back a bit, and, as a result, the balance of the ensemble was tilted a mite too far in favor of the harp. Happily, Ms. Zhou is an extraordinary musician, so this, in and of itself, wasn’t a bad thing: she brought a great range of colors to her very involved part and made this rather formidable score come across as nothing too challenging.

Ms. Zhou then got her solo turn after intermission in Mikhail Mchedelov’s Variations on a Theme of Paganini. The Paganini theme in question was that of the famous 24th caprice (for solo violin), which has been the basis for compositions by composers ranging from Liszt to Lutoslawski. Mchedelov wrote 11 Variations on this tune, most of them fast, all of them—for the harpist—nice and flashy. Even if there wasn’t much to the piece musically, Ms. Zhou turned in a performance that was committed and vibrant. For me, her best moments came just before the work ended: the wholly idiomatic harp cadenza was played with great character, while she again brought out beautiful instrumental colors in her reading of the work’s slow movement.

To close the concert, the CCP turned to a very new piece, one that premiered last summer, in fact: the La Jolla Quartet of John Williams. Mr. Williams is, of course, best known as a composer of film music, though from time to time he’s dabbled in writing concert music, too. This quartet, for clarinet, violin, cello, and harp was composed for a La Jolla, California-based, music festival run by the violinist Cho-Liang Lin (hence its title). However, there is a strong local connection written into the piece: former BSO principal harp Ann Hobson Pilot, Mr. Williams writes, was the “spiritual guide” to the Quartet’s second movement.

In his program note (as well as in a letter from the composer that Ms. Putnam read to the audience), Mr. Williams talks about his excitement in exploring different instrumental sonorities while he was composing the work, and, indeed, many moments in the piece feature ear-catching instrumental combinations and effects. Fetching as these moments are, in terms of its musical content Mr. Williams’s Quartet is a bit long-winded: throughout the performance, I was reminded of the old adage that less is, in fact, more and wished that Mr. Williams had perhaps considered some of the wisdom inherent therein.

Still, it’s a nice enough work that was given a committed performance by Ms. Putnam, Ms. Zhou, Mr. Martin, and cellist Mickey Katz. I thought the best of the Quartet’s five movements were the second and fourth. The former (for which Ms. Hobson Pilot served as “spiritual guide”) features long melodic lines played in octaves by the strings and clarinet; the harp fills in rapid figurations between the lines of the slowly unfolding melody to fine, atmospheric effect. In the latter movement, Mr. Williams indulges in his jazz background with an essay for clarinet that is often accompanied by a kind of walking bass in the cello.

The other three movements are up-tempo and energetic, if not particularly memorable, musically. There were a couple of moments in them where the composer of E.T. and Star Wars seemed to be hiding behind a shroud; I only wished that side of Mr. Williams’s musical personality had been more forthright in making his presence known.

Oh well. The players in the quartet were as involved as one hoped they might be in this piece, and they seemed to particularly enjoy the quasi-Bartòk major/minor chords in the finale. If not the most compelling example of new chamber music, the La Jolla Quartet is definitely one of the friendlier, and that spirit certainly came across in the CCP’s performance.

Next up for the CCP is a concert in March by the Brentano Quartet. By then it might be a bit warmer and we should only have college basketball to worry about, so get your tickets now!

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.