Classical Music Review: The BSO — A Chemistry Lesson

It was clear from the moment Ludovic Morlot mounted the podium that he and the Boston Symphony Orchestra possess a strong chemistry: the players clearly respect him and they responded to his leadership with precision, energy, and feeling.

Richard Goode, Elizabeth Rowe, the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and Ludovic Morlot. At Symphony Hall, Boston, MA, November 19, 2011. The program repeats Tuesday night (November 22) at 8 p.m. at Symphony Hall.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

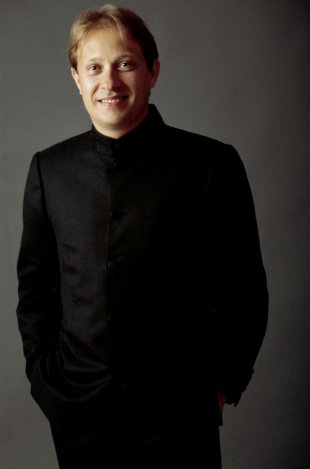

Conductor Ludovic Morlot — does the Orchestra ultimately have a more permanent position in mind for him?

What a difference a week (and a conductor) makes! Last week, I reported on an interesting Boston Symphony Orchestra (BSO) program that, while technically secure and well played, I found severely lacking, interpretively. This weekend the orchestra was back with a new maestro and another fascinating program—one that, in fact, recalls the adventurous first seasons of James Levine’s music directorship—and the result was one of the most richly satisfying performances I’ve heard this illustrious ensemble give.

Ludovic Morlot, music director of the Seattle Symphony (and former BSO assistant conductor), returned for the first of two weeks of subscription concerts he is leading this season. Pianist Richard Goode joined him in a Mozart concerto, and BSO principal flute Elizabeth Rowe took the solo spotlight in a piece by Elliott Carter; scores by Berlioz and Bartòk rounded out the program.

It was clear from the moment Mr. Morlot mounted the podium that he and the Orchestra possess a strong chemistry: the players clearly respect him, and they responded to his leadership with precision, energy, and feeling. He, in turn, brought out the best of their collective musicianship.

Mr. Morlot began by leading the BSO in a crisp, incisive performance of Hector Berlioz’s Roman Carnival Overture. In his Memoirs, Berlioz had little good to say about the years he spent living in Rome in the early 1830s, though his animosity probably had more to do with the lack of musical opportunities in the city and homesickness than anything else. Little of that distaste made it into the present Overture (which was cobbled together from excerpts of his failed 1838 opera Benvenuto Cellini), though some of its opening material suggests the melancholy Berlioz experienced while wandering the Italian countryside in those years.

The Overture has been a staple of the BSO repertoire for nearly 130 years, and that familiarity was evident in the orchestra’s wholly characteristic performance Saturday night. Robert Sheena’s English horn solo in the slow, opening section was played with sensitive dolorousness, as was the viola melody that leads into the climax of the work’s first half. In the fast, second section, brass and percussion (including tambourine) gamely led the way while the strings and winds shaped Berlioz’s off-kilter, rhythmic phrases with playful agility. Throughout the performance, Mr. Morlot kept textures clear and dramatically enunciated the huge range of dynamic shadings for which the score calls.

Following the Berlioz, the eminent Mr. Goode appeared as soloist in Mozart’s Piano Concerto no. 25 (KV 503). This Concerto was the last of a dozen that Mozart wrote between 1784 and 1786 to showcase his own skills as pianist and composer in concerts he was giving in Vienna. It’s very personal music, its pages filled with characteristics one also gleans from reading Mozart’s letters: by turns playful, subdued, extroverted, and brilliant.

Mr. Goode, who played his own fine cadenzas, gave a nicely shaped account of the solo part. In this Concerto, the solo piano inhabits two worlds. In the first, it is front-and-center as soloist. In the other, it plays an active, but subservient, role within the orchestra. Mr. Goode seemed equally at home in both, always maintaining good eye contact with Mr. Morlot and the members of the orchestra. The outer movements, particularly, are filled with much harmonic ambiguity, and Mr. Goode played up these contrasts to fine effect. The second and third movements, too, had a nicely improvisatory quality that is difficult to articulate: suffice it to say, there was a spontaneity to Mr. Goode’s performance that was refreshing.

Mr. Morlot and the orchestra were sensitive accompanists. A few brief moments of ensemble disunity notwithstanding, there were fine, solo woodwind contributions in the second movement and, throughout, a chamber music-like quality to the performance.

After intermission, Ms. Rowe gave a commanding and energetic performance of Elliott Carter’s Flute Concerto (written in 2008). Like the Mozart, Mr. Carter’s score is a study in contrasts: of energy, stasis, timbre. While Mr. Carter’s post-serial aesthetic might not be to everyone’s taste, the BSO plays his music as well as anybody—which is to say, very well. And though I’ve not always had the greatest sympathy for Mr. Carter’s musical language, there is much to commend and admire in this Concerto.

Ms. Rowe’s performance was beyond reproach. She handled the intricacies of Mr. Carter’s writing with aplomb, shaping her flurries of notes with warmth and sensitivity. For me, the highlight of her performance came in the Concerto’s second section, where, after fitful bursts of orchestral activity threatened to derail the solo flute, Mr. Carter wrote a lovely melody that spans much of the instrument’s range. This slow section was played with great warmth of tone and delicate, dynamic shadings.

For his part, Mr. Morlot drew breathtakingly clear textures from the orchestra throughout their performance of this rhythmically complex score, while effectively playing up the many contrasts of mood and character in the music. I was continually impressed by Mr. Carter’s ear for novel instrumental combinations (harp, vibraphone, and piano being one of many) and the ways the solo flute is balanced with the chamber-sized orchestra. In a conversation from 2003 quoted in the program book, Mr. Carter—who celebrates his 103rd birthday on December 8th—spoke of the process of writing music as being “in a situation of great adventure,” and that spirit permeates this engaging 14-minute work.

Elliott Carter’s engaging Flute Concerto was performed — the composer celebrates his 103rd birthday on December 8th.

To close the evening, Mr. Morlot and the orchestra turned to the music of one of the last century’s great modernists, Belá Bartòk’s Suite from The Miraculous Mandarin. The Suite, which dates from 1927, consists of the first two-thirds of Bartòk’s score for his “pantomime” The Miraculous Mandarin. Its plot, among the more sordid to come out of the 1920s (which is saying something), involves a girl and three hoodlums and their attempts to rob unsuspecting men the girl seduces; the work was subsequently banned after its first performance in Germany in 1926.

On Saturday, the BSO gave a thrilling, edge-of-the-seat performance of this extraordinary piece. The opening section, in which Bartòk created an aural depiction of a bustling city, was played with wild abandon and not a little aggression. There were notable solos throughout the softer, waltz-like sections that follow, including principal clarinet William Hudgins’s and principal oboe John Ferrillo’s warmly shaped turns. The whole performance, though, was an opportunity for the BSO to shine, and shine they did: mid-performance, I found myself realizing that The Miraculous Mandarin is but a hard-edged preview of what Bartòk later wrote in the Concerto for Orchestra. The work’s closing section—one of Bartòk’s wildest creations—was dispatched in an exhilarating, brutal spirit, replete with snarling trombones, swirling woodwind figurations, and a percussive ostinato that built to a ferocious din.

Mr. Morlot’s command of this score was thoroughly impressive. Not only did he enunciate the work’s dramatic structure, but he also made strikingly clear Bartòk’s sometimes knotty orchestral textures, and he achieved this without diminishing the innate muscularity found in Bartòk’s music. The result was a performance that was nuanced and delicate, yet full and strong—a truly exceptional episode of music making.

After Thanksgiving, Mr. Morlot returns to Symphony Hall to conduct music by John Harbison, Ravel, and Mahler and in mid-December leads the BSO on a West Coast tour. Does the orchestra ultimately have a more permanent position in mind for him? After the superb results of this weekend, I certainly hope so; stay tuned.

The program repeats Tuesday night at 8 p.m. at Symphony Hall. Don’t miss it.

Tagged: Boston Symphony Orchestra, Elizabeth Rowe, Ludovic Morlot