Theater Reviews: Broadway —The Importance of Being Earnest and Jerusalem

Terrific that Mark Rylance won a Tony Award for his performance in JERUSALEM, one of two New York stage productions that offer sterling examples of going maximalist in an increasingly minimalist age.

The Importance of Being Earnest: Live in HD by Oscar Wilde. Directed by Brian Bedford. Presented by L.A. Theatre Works, BY Experience, and the Roundabout Theatre Company at the American Airlines Theatre, New York, New York. The Broadway production runs through July 3, 2011. Screenings of the HD performance will be at various cinemas throughout New England (check website and list below).

Jerusalem by Jez Butterworth. Directed by Ian Rickson. Staged by the Royal Court Theatre at The Music Box, New York, New York, through August 21, 2011.

By Bill Marx

In Vanishing Acts, his collection of critical pieces on the theater since the 1960s, Gordon Rogoff notes that the “source of the best modernist acting is the actor’s willingness to make the performance itself more important than sympathy; far from commenting on the character’s situation, the actor is now offering no-comment, another kind of distancing in which the character is laid out before us like Eliot’s patient etherized upon a table.” Cool is more difficult and riskier, but it provides much more aesthetic exhilaration for an audience than coddling.

Of the two New York shows under review, Roundabout Theatre Company’s (RTC’s) thoroughly enjoyable The Importance of Being Earnest, which I saw via a HD screening at the Coolidge Corner Theatre (additional screenings in New England will take place throughout June), occasionally slobbers a bit for audience approval, but director Brian Bedford realizes that the witty solipsists in his masterpiece should be approached with a clinical, Mozarian passion that has nothing to do with the brute sentiment of the sitcom or the slam-bang syncopation of farce. Wilde’s laughs are released via nuanced vocal inflection, a calibration weighted in self-admiring reserve, rather than overt clowning—there is no need to signal that the proceedings are funny.

The accents are in sync, Bedford’s staging moves along on nimble feet and tongues, and the costumes and sets are lushly and suitably stylized. As for the performances, the men in the cast outshine the women, with Dana Ivey coming on like puritanical gangbusters as Miss Prism, while the Gwendolen Fairfax of Sara Topham and Cecily Cardew of Charlotte Parry veer toward the monotone, though the fur flies during their teatime fracas. David Furr brings plenty of anger and frustration to John Worthing: he is not all that likable a suitor, which is refreshing, while Santino Fontana’s Algernon Moncrieff is irritatingly impish, not glibly playful, which is also a smart choice. “Bunburying” is not just about escaping society—it is, as Worthing comes to realize, part of a search to do away with the conventional.

As for Bedford, he has a highly amusing time playing Lady Bracknell as a colorfully be-gowned sourpuss of hare-brained respectability, the only adult in the room being the most childish of the lot. Understandably, the camera sticks to Bedford, and that is unfortunate—at times it would be nice to see the reaction of those on the receiving end of Bracknell’s zingers. I like my Bracknells meaner and more Gorgonish (they are society’s power brokers after all); Bedford’s interpretation leans toward the grouchy rather than the imperious (his facial reactions can be cartoonish), which softens the character around the edges. But the performer’s vocal gymnastics are thrillingly adept, his voice fluctuating from high to low, depending on Bracknell’s proximity to incredulity. And the incredible is never all that far away in this production’s robust vision of Wilde’s satiric and antic world.

The contrast between how Brits and Americans package theater in HD falls into predictable stereotypical grooves. Here it is all about taking the audience by the hand, forgoing even intimations of substance for salesmanship, glitz, and product placement. David Hyde Pierce is our guide before the show and during intermission, walking about the theater, cracking jokes, (ironically?) telling HD audiences to take in live theater, whisking us backstage for a wry interview with Bedford, then introducing sped up footage of the actor’s transformation into Lady Bracknell. All this is slickly done, making use of a variety of camera angles—the canned promos for the Roundabout Theater Company and L. A. Theatre Works are sensational enough to satisfy Wilde. The clunky moments come when Alfred Molina interviews an academic expert on Oscar Wilde, the result a rambling conversation that contributes little valuable information, essentially serving as yet another plug for L.A. Theatre Works.

Screenings of the RTC’s production of The Importance of Being Earnest in New England during June

MASSACHUSETTS

Julie Harris Stage (Wellfleet, MA) – June 11, 18, 25

Mahaiwe Performing Arts Center (Great Barrington, MA) – June 9

Shalin Liu Performance Center (Rockport, MA) – June 5

The Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute (Williamstown, MA) – June 18

CONNECTICUT

Katharine Hepburn Cultural Arts Center (Old Saybrook, CT) – June 7

Quick Center for the Arts (Fairfield, CT) – June 10

VERMONT

Town Hall Theater/Opera Company (Middlebury, VT) – June 12

NEW HAMPSHIRE

Hopkins Center for the Arts at Dartmouth (Hanover, NH) – June 24, 25

MAINE

The Grand Auditorium (Ellsworth, ME) – June TBC

The Strand (Rockland, ME) – June 5, 7

Regarding Jerusalem, Caldwell Titcomb wrote about the British production of the play for the Fuse in September 2, 2009. Based on his high recommendation, I saw the show a few weeks ago. Here are his thoughts:

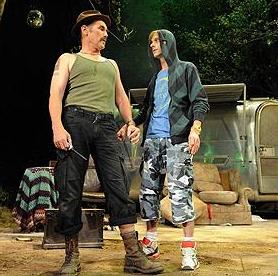

Mark Rylance and Mackenzie Crook in the Royal Court production of JERUSALEM (Photo: Alistair Muir)

Jez Butterworth’s latest play, Jerusalem (Royal Court), is shocking, sprawling, in-yer-face . . . and hilarious. It takes place in and in front of a run-down mobile home sitting in a clearing in the woods. Lording it over everyone and everything is Johnny “Rooster” Byron (Mark Rylance), a tattooed 50-year-old ex-daredevil and spiller of tall tales (“My mother was a virgin when she bore me”). He is a charismatic figure who attracts people of all ages—especially teenagers, whom he supplies with booze and drugs (he calls them “my band of educationally subnormal outcasts”). Twice the local officials try to serve him an eviction notice, which he finally takes and sets fire to as he pulls out another bottle of whiskey.

Rylance is an actor of amazing range (he won the best-actor Tony Award this year for his Broadway performance in the godawful Boeing-Boeing), and his work here is absolutely astonishing; I can’t think of another actor in the world who could match it. Ian Rickson has directed his 14 players flawlessly.

I don’t have a lot to add about the excellent American production, which has been extended until August 21st, no doubt because of the Tony Award nomination for Rylance. Anyone interested in seeing high-stakes, bravura stage acting (which is becoming increasingly rare in these tepid times), a gargantuan blend of energy and control, subtlety, and broad strokes, should take in this exciting performance. This is modernist acting of high caliber—Rylance is not only icily neutral about the amoral Johnny “Rooster” Byron, he rejects the sympathy of the audience at every turn.

Because of the domination of television and movies, acting on stage has become increasingly miniaturized and realistic, with scripts written to match the tastes of audiences who are preternaturally sensitive about performances that attempt exaggeration and over-sized passion. The studious application of small, tell-tale details is an important part of generating audience sympathy. It is the theater’s loss, and the focus on the small-grained familiar helps explain why there is so much more music in theater today (the Diane Paulus phenomenon)—audiences are willing to accept grand gestures when they are accompanied by tunes.

Those who remember Rylance as the mewling, pajama-clad Prince of Denmark in the American Repertory Theatre’s 1991 production of Hamlet will be flabbergasted—here he comes off as a powerful, dangerous, chaotic force, a fascinating, fowl-mouthed mix of pagan devil and secular savior. I have more reservations about Butterworth’s play than Caldwell and the NYT‘s Ben Brantley. But it is easy to forgive the script’s shaky zigzags from the realistic to the mythic and back, even an unconvincing mix-and-match of an ending.

This is an ambitious, iinguistically nervy “State of England” play, funny, amoral, and pungent, that draws on the poetic/anarchistic political tradition of the grievously neglected dramatist John Arden as well as on Peter Barnes’ tragicomic chronicles of an alternative community of outliers broken up by external and internal betrayals. The important point is that Rylance and Butterworth grab at the the opportunity to go maximalist in a minimalist age—and they make the savage most of it.

Tagged: contemporary, England, English drama, Jersalem, Mark Rylance, Music Box, Royal Court Theatre