Opera Album Review: Racine’s Tragedy “Andromaque” Finds New Life in Rossini’s Splendidly Serious “Ermione”

By Ralph P. Locke

Another excellent recording from the “Rossini in Wildbad” festival, with spellbinding vocal performances by Congolese tenor Patrick Kabongo and other powerful young singers.

Serena Farnocchia (Ermione), Aurora Faggioli (Andromaca), Moisés Marín (Pirro), Patrick Kabongo (Oreste), Chuan Wang (Pilade), Jusung Gabriel Park (Fenicio).

Krakow Philharmonic Chorus and Orchestra, cond. Antonino Fogliani.

Naxos 8.660556-57 [2 CDs] 133 minutes.

Beethoven reportedly advised Rossini to stick to comic opera. Rossini ignored the advice, and his many serious operas became the stylistic and structural basis upon which Bellini, Donizetti, and the young and mid-career Verdi built their world-renowned works.

In recent decades, Rossini’s serious operas, many of them written for the San Carlo Theater in Naples, have been successfully revived in opera houses and on recordings and video, thanks in large part to singers who have trained their voices to handle the luxuriant coloratura that these works require. It also helps that opera festivals have sprung up using auditoriums that are not as mammoth as places like the Met or Chicago’s Lyric Opera, so the singers aren’t tempted to try to reach the back rows through volume or overemphasis.

The Rossini in Wildbad Festival has been among the best of these festivals, bringing the opera-loving world one half-forgotten Rossini opera after another (comic, too, not just serious), and also equivalent works of Rossini’s contemporaries (Arts Fuse review of Johann Simon Mayr’s L’Accademia di musica) and followers (e.g., Bellini). I have hailed many of the resulting recordings, made in conjunction with Deutschlandfunk Kultur (German Radio, “culture” channel) and released by Naxos. Nearly all come with an excellent booklet-essay and synopsis in German and English and put the Italian libretto up on a website. All of that is true for the current release, which amounts to the fifth, I believe, commercial rendering (counting one DVD from Glyndebourne) of Rossini’s 1819 opera Ermione, based on Racine’s renowned tragedy Andromaque (1667), which I remember studying in French class in high school!

The performance hall (the Royal Spa Theater) at the Rossini in Wildbad Festival. Photo: courtesy of the festival.

One of the great things about Rossini’s serious operas is that they are orchestrally accompanied all the way through — no tinkling fortepiano or whatever. This allows Rossini to make the passages of speechlike interchange more interesting and varied. Indeed, there ends up being much that is not predictable in Rossini’s serious operas. The overture to Ermione is interrupted by an offstage chorus of Trojan captives, bemoaning their kingdom’s defeat at the hands of the Greeks. And numerous musical numbers feature prominent solo passages for a flute, a clarinet, two horns, and so on, or an offstage march indicating that a wedding is about to occur. (The wedding distresses the title character, Ermione, who wants the King of Epirus, Pirro, for herself, yet he insists on marrying Andromaca, despite the fact that the latter wishes to remain faithful to the memory of her husband Ettore, whom Pirro killed in battle. You may know many of these characters by their Englished names: Hermione, Pyrrhus, Andromache, Hector.)

Most of all, the melodies are as attractive and the harmony and orchestral figurations are as engagingly handled as in the (much better-known) comic operas by the same composer, such as The Barber of Seville or La Cenerentola. Anyone who knows one of the more frequently performed Rossini serious operas, such as Semiramide or Moses in Egypt (I reviewed Rossini’s own French adaptation of Moses) will already look forward to some of the work’s strongest features, such as Orestes’s highly florid “Reggia aborrita!” (Oh, royal palace that I despise!) or the slow interlocking coloratura passage for Ermione and Oreste that launches the immense 17-minute Act 1 finale. Ermione was one of many operas that Rossini composed for the troupe of world-class singers that he had built at the San Carlo Theater in Naples, including two amazing coloratura tenors: the high-flying Giacomo David and the somewhat more baritonal and dramatically intense Andrea Nozzari. In this case, he, sensibly enough, assigned the bad-guy role of Pirro to Nozzari and thus felt free to dot the role with stentorian cries suitable to an enraged autocrat unaccustomed to being denied his fondest wishes. (These operas from two centuries ago can nowadays sound startlingly up-to-date.)

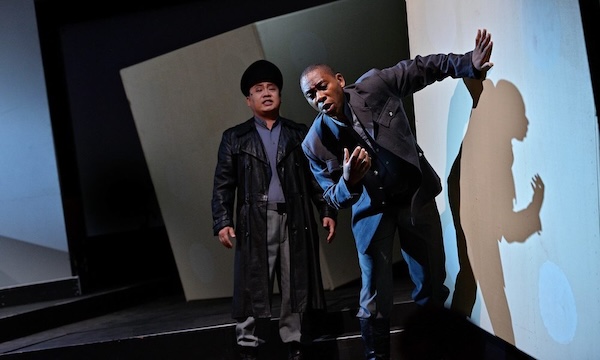

A scene from the Rossini in Wildbad Festival’s production of Ermione. Photo: Patrick Pfeiffer

All of this would matter little if the performers on the new recording from the 2022 Wildbad Festival weren’t splendid. But they are, especially the two leading women: soprano Serena Farnocchia (as Ermione) and alto Aurora Faggioli (as Andromaca) and tenors Patrick Kabongo from the Democratic Republic of Congo (as Oreste, who keeps pursuing Ermione in vain) and, only slightly less polished, Moisés Marín from Spain (as King Pirro, who so cruelly insists on his right to force Andromaca into marriage). (For more on the qualities of these four leading singers, see the astute review by Mike Parr, who chose the recording, taken as a whole, as one the best releases of 2024.) A third tenor, Chuan Wang from China, makes a glorious impression in the secondary role of Orestes’s friend Pilade (the character known as Pylades in English). I see that Wang has been singing lyric roles (Mozart’s Ottavio, Puccini’s Pang) in Turin and other important European opera houses.

It helps greatly that Farnocchia and Faggioli are native Italian-speakers and probably also that the conductor, Antonino Fogliani, is likewise Italian: I have rarely in recent years heard operatic exchanges in Italian rendered with such attention to verbal values, even while musical considerations were in no way being shortchanged. I was reminded of some passages in older recordings, where, for example, Ebe Stignani and Mario Filippeschi — in an early Norma starring Maria Callas — sounded like they were truly having a conversation in front of us.

Tempos are wisely chosen but artfully shaded in responses to harmonic shifts; the smallish chorus and orchestra (both from Poland, though the orchestra is perhaps staffed in part with foreigners) sound spiffy; and the wind soloists are of international caliber, with no squawking or doubtful intonation.

A scene from the Rossini in Wildbad Festival’s production of Ermione. Photo: Patrick Pfeiffer

We are lucky to have Ermione available this way, to add to the excellent recordings featuring Cecilia Gasdia (made in 1986) and Carmen Giannatasio (Opera Rara, made in 2009). The latter two are now available in rereleases, the Opera Rara one in a box with two other Rossini operas (which I hailed here). Whichever recording you listen to, you can download the Italian libretto for free at www.naxos.com, and in Italian and good English at the Opera Rara site.

I urge opera lovers to get to know Ermione and the other Rossini serious operas, such as those I have reviewed previously: Adelaide di Borgogna and Sigismondo (in a single review), Demetrio e Polibio and Bianca e Falliero (in American Record Guide, March/April 2018), Aureliano in Palmira, Maometto II, Eduardo e Cristina, Zelmira (Paris version, 1826), Moïse (Moïse et Pharaon; ou, le Passage de la Mer rouge), and Matilde di Shabran. Beethoven knew best what projects he himself should undertake; about Rossini, he was wrong wrong wrong.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). He is part of the editorial team behind the wide-ranging open-access periodical Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal. The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and is included here by kind permission.

Tagged: Antonino Fogliani, Ermione, Gioacchino Rossini, Kraków Philharmonic Chorus and Orchestra, Naxos, “Rossini in Wildbad”