June Short Fuses — Materia Critica

Each month, our arts critics — music, book, theater, dance, television, film, and visual arts — fire off a few brief reviews.

Classical Music

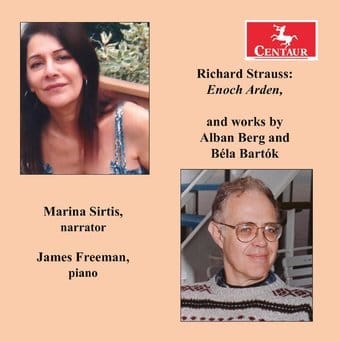

Three major works from the years 1897 to 1939 make a refreshing offering in a CD album (or digital download) by the extremely artful pianist James Freeman. (Click here to hear any track. I loved his previous release.)

Three major works from the years 1897 to 1939 make a refreshing offering in a CD album (or digital download) by the extremely artful pianist James Freeman. (Click here to hear any track. I loved his previous release.)

Richard Strauss’s Enoch Arden (1897) is an engaging work for narrator with highly descriptive accompaniment. The 1864 Tennyson poem has been freely adapted in many media (including in the film Cast Away). Its basic plot: A fisherman goes off to sea, gets stranded on a Pacific island, and, 10 years later, returns. He finds that Annie, though heartsick at his apparently having died, has eventually remarried and had a young child, while one of Enoch and Annie’s children has died and the other two accept the kindhearted Philip as their new father.

I took the opportunity to listen to four previous recordings that feature major narrators: Claude Rains, Patrick Stewart, Christopher Kent, and (in German) Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. James Freeman has had the imagination to choose the artful Marina Sirtis, best known as Counselor Deanna Troi in the TV series Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987-94). The excellent in-concert acoustics of Swarthmore College’s Lang Concert Hall help us feel that Sirtis is confiding this story to us on a long winter’s night, skillfully differentiating each villager who speaks. Strauss’s imaginatively varied music reinforces the tale at every touching turn.

Alban Berg’s sole, impassioned Sonata for Piano (Op. 1, 1908; the composer was a mere 23) has never been conveyed more vividly or coherently, nor sounded quite so Brahmsian in its continuous reworking and reharmonization of distinctive melodic phrases.

The program ends with the effervescent “Six Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm” (1939) — the culminating pieces in Bartók’s massive collection of piano pieces, Mikrokosmos. Freeman plays them with vigor, clarity, and appropriate, quasi-improvisatory rhythmic freedom.

— Ralph P. Locke

New Moon, an album of art songs honoring American women composers, celebrates 10 years of Calliope’s Call, founded by mezzo-soprano Megan Roth, whom I have known as a singer with the superb Skylark Vocal Ensemble. This album, dedicated to songs and poetry composed and written by women, is a gem. Founded to promote and “uplift” underrepresented voices through the genre of art song, the success of Calliope’s Call suggests — along with the attention garnered by women composers over the past decade — that at this point in time female composers and poets can no longer be seen as being overlooked or ignored. That said, New Moon will certainly aid the cause of giving worthy women musicians and poets some well-deserved attention.

New Moon has a variety of things going for it. The two singers, Megan Roth and soprano Evangelina Leontis, and their pianist, JJ Penna, are exceptionally eloquent. The compellingly entertaining poetry chosen by the album’s composers is fabulous. Just reading the list of songs provides chuckles. My favorites were the provocative tracks “Love After 1950” (sung by Megan Roth, music by Libby Larsen), “Boy’s Lips” (a blues), “Blond Men” (a torch song), “Big Sister Says 1967,” (a honky-tonk), and “The Empty Song” (a tango).

Roth chose her composers with care, and the music reflects her good taste. A number of them are new to me, but I would love to hear more of their music: Sarah Hutchings, Jody Goble, Marion Bauer, and Gilda Lyons. The latter’s sole contribution was deeply touching — a lovely arrangement of the Irish ballad “The Parting Glass,” sung unaccompanied by the recording’s two singers. There is much to enjoy and admire on this disc, including verse from the well-known poets Rita Dove and Muriel Rukeyser, along with the contributions of their sister-poets, Julie Kane, Kathryn Daniels, and Liz Lockhead.

— Susan Miron

If you’re looking for rigorously structured, long-form musical arguments, you won’t find them on Breve, the Euclid Quartet’s 25th-anniversary release (Afinant Records). Neither will you discern any but the most tangential thematic or musical connections between the disc’s 11 tracks.

What does unify this celebratory album is, instead, duration: though a couple try, none of the recording’s selections cross the nine-minute mark. Several, like the Polka from Shostakovich’s The Age of Gold, Astor Piazzolla’s Four for Tango, and William Bolcom’s Graceful Ghost Rag, might qualify as bona fide encores.

But most of the rest are weightier. And getting to hear them together in this context — one can listen to the album straight through or on shuffle — is instructive.

It turns out that George Gershwin’s bluesy Lullaby fits as well with Giacomo Puccini’s Crisantemi as it does Hugo Wolf’s zesty Italian Serenade. And that Javier Alvarez’s jaunty Metro Chabacano, Mozart’s taut C-minor Adagio and Fugue, and Joaquin Turina’s shimmering La Oracion del Torero make for an enticing sequence.

All of those come over in excellent sound and with an abundance of musical character, the Euclids shifting with complete surety and ease between their varied styles. Fittingly, the group is most impressive in their two biggest items, Schubert’s Quartetsatz and Anton Webern’s Langsamer Satz. Both are beautifully textured and smartly directed, the latter unfurling with flowing urgency and sumptuous lyricism.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

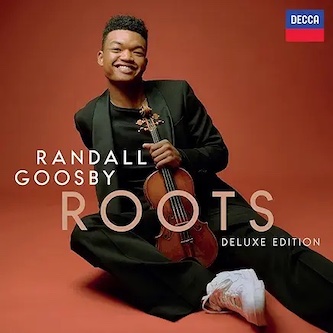

Deluxe- and extended edition releases are sometimes geared more toward collectors than anyone else. But whenever you get the chance to hear more from violinist Randall Goosby, the investment is well worth the effort.

That’s certainly the case with Roots (Deluxe Edition) (Decca), the “new” version of Goosby’s superb 2021 debut album that’s been expanded to include five new pieces, four by composers already featured on the disc (Coleridge-Taylor Perkinson, William Grant Still, Florence Price, and Samuel Coleridge-Taylor) plus one by Carlos Simon. They fit seamlessly into the lineup.

Goosby plays Simon’s hymn-like Hold Fast to Dreams with enchanting purity, his fiddle coming about as close to truly singing as the instrument can. Ditto for the violinist’s performance of Coleridge-Taylor’s Cavatina. In the last, too, pianist Zhu Wang imbues the often-mobile keyboard writing with winning lightness and lyricism.

Price’s Elfentanz and Still’s Here’s One offer, respectively, charm and soulful declamation, while Perkinson’s grooving Louisiana Blues Strut receives a supremely elegant — but totally knowing — interpretation.

The rest of the album holds up very well after three years, especially Xavier Foley’s Shelter Island and Still’s Suite for Violin and Piano. If you missed it the first time around, then, no worries: Roots (Deluxe Edition) is the edition of choice. Goosby remains a violinist with much to say and a compelling ability to tell his stories. As it turns out, the bigger and longer they are, so much the better.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

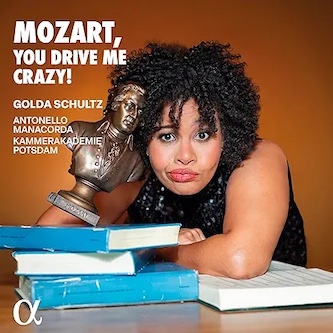

Props to soprano Golda Schultz for coming up with one of 2024’s best classical album titles. Also, for demonstrating that she’s one of the great Mozart singers of her generation.

Props to soprano Golda Schultz for coming up with one of 2024’s best classical album titles. Also, for demonstrating that she’s one of the great Mozart singers of her generation.

Mozart, You Drive Me Crazy! celebrates, mainly, the musical, technical, and dramatic complexities of the lead female characters in the Mozart-da Ponte trilogy (Le nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni, and Così fan tutte). It doesn’t delve into the moral ambiguities of, especially, the last, but that’s not its purpose. The results are, in a word, excellent.

Schultz, it emerges, is a terrific Donna Elvira, Donna Anna, Susanna, Contessa, and Fiordiligi. Don Giovanni’s “Or sai chi l’onore” soars with uncommon radiance while the runs in “Mi tradì quest’alma ingrata” are the picture of agility.

Figaro’s “Deh vieni non tardar” showcases Schultz’s rich low register, “Dove sono” her subtle improvisational skills. Meantime, Così’s “Come un scoglio” features graceful, conversational interactions between soprano and the excellent Kammerakademie Potsdam and conductor Antonello Manacorda, while “Per pietà” is pretty much faultless.

What’s more, Schultz imbues the various recitatives with fire: they’re almost as ear-catching as her program’s arias and ensemble numbers. In the latter, the soprano’s joined by members of a well-matched septet: Julie Roset, Amitai Pati, Ashley Dixon, Milan Siljanov, Simone Easthope, Pawel Horodyski, and Samuel Dale Johnson (they all join in on the last track, a rousing rendition of Figaro’s “Gente gente, all’armi, all’armi!”).

Together, the collective reminds that, for all its difficulties, this is music of exceptional beauty, originality, and emotional range. That they accomplish as much without a hint of fussiness and in such familiar fare is the album’s real story — and, let’s face it, that might be enough to drive other musicians crazy with envy.

— Jonathan Blumhofer

Roots and World Music

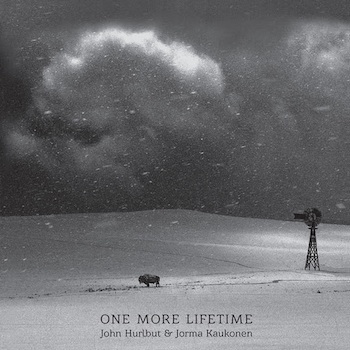

Spotlighting John Hurlbut’s rustic vocals and rhythm work and Jorma Kaukonen’s mesmerizing leads, One More Lifetime (Culture Factory USA) is an indispensable album for fans of acoustic guitar. The third Hurlbut-Kaukonen collaboration since 2021, the recording testifies to how deeply long-term personal relationships can enrich artistry. Hurlbut and Kaukonen have known each other for 40 years, and that kinship infuses their performances with a powerfully intuitive conversational flow. Kaukonen has the same kind of connection with bassist Jack Casady, via their long-running outfit Hot Tuna.

Spotlighting John Hurlbut’s rustic vocals and rhythm work and Jorma Kaukonen’s mesmerizing leads, One More Lifetime (Culture Factory USA) is an indispensable album for fans of acoustic guitar. The third Hurlbut-Kaukonen collaboration since 2021, the recording testifies to how deeply long-term personal relationships can enrich artistry. Hurlbut and Kaukonen have known each other for 40 years, and that kinship infuses their performances with a powerfully intuitive conversational flow. Kaukonen has the same kind of connection with bassist Jack Casady, via their long-running outfit Hot Tuna.

Kaukonen leaves the vocal work to Hurlbut. In this setting he is content to just play guitar — doing so with a heightened sense of exploration and theatrical flourish.

This project grew out of a series of concerts Kaukonen live-streamed from his Fur Peace Ranch in Ohio during the pandemic. The duo sticks to what has become a successful formula: a couple of Hurlbut originals and some intriguing cover tunes. The opening track is Peter Rowan’s haunting ode to the lovelorn, “Angel Island.” This poetic ballad defies easy classification; Kaukonen and Hurlbut do it justice through their delicate treatment of its lead guitar parts and an ache in the vocal delivery. Similar pangs of desire pop up in the hard country vibe of David Wiffen’s “Lost My Driving Wheel” and the crisp bright tones of Bob Dylan’s “I’ll Remember You.”

For “Operator,” Hurlbut and Kaukonen play it straight, digging deep into the funky hoot in this folk blues lament by the Grateful Dead’s Ron McKernan. Similarly, the duo airs out Fred Neil’s “Everybody’s Talking” via an uncluttered arrangement that digs into the tune’s wistful core.

Hurlbut’s own “Day in the Country” celebrates pastoral life over city living. It is wryly positioned alongside Woody Guthrie’s “Pastures of Plenty,” which deals with migrant workers bereft of the comforts their labor provides city folk. Hurlbut’s “Lazy Saint” closes the record aptly; it is a rich tapestry of intertwined guitar parts that resonates with the natural connection between these two musicians.

— Scott McLennan

The cover art for Pomme’s Saisons. Photo: Sois Sage Musique

A multi-hyphenate singer at the intersection of pop, indie, folk and rock, Pomme is beginning to garner global traction, especially in the US and South America. But she remains loyal to her roots in Lyon, France — the birthplace of her chanson française style.

Written by Pomme in between living in France and Canada during the pandemic, the 12 tracks of Saisons are structured into four three-song orchestral chamber-folk acts beginning in spring and more romanticized sensations with “_mar le temps des fleurs” (“The time of the flowers”), and continuing into April and May (“_apr les temps des fleurs,” “_may les temps des fleurs”). Pomme calibrates her emotional reactions to the seasons from a very personal perspective. This is a compellingly internal, at times surrealist, vision of time passing as the singer/songwriter experiences it.

The first track, (“_mar le temps des fleurs”), begins in March and delves into spring. Filled with images of migration, Pomme bids birds goodbye as they “envoler vers le nord” (fly to the north). She welcomes the temperate weather, repeating– “c’est le temps des fleurs” (it’s flower time). Summer focuses on romance. In her lyrics for “_jun perseides” (June Perseids) Pomme reminisces about her experiences of intimacy, at one point musing, “Pendant l’été où je t’ai rencontré par magie/…C’est là qu’on s’est aimé pour la première fois” (During the summer when I met you by magic/…This is where we first fell in love”).

The unifying capstone of Saisons is its instrumental windup, “_feb carte de noël” (Christmas Card). Marking the end of Pomme’s winter, the song skillfully intertwines a sense of listless frigidity with memories of the jubilation of spring to come: notes reminiscent of chirping birds intermingle with melancholic melodies. That dramatic contrast epitomizes the passionate melodrama of an album that taps into feelings of lust, detachment, appreciation, and sadness. Pomme will be performing at The Sinclair on June 12.

— Kayleigh Schweiker

Eric Chenaux Trio. Photo: Sylvestre Nonique-Desvergnes

Eric Chenaux’s music is half past, half future. His current trio pays homage to the tradition of jazz torch songs, while his solo music has pulled from folk and blues. (The Canadian singer/guitarist began making music with the ’90s Toronto punk band Phleg Camp.) As many have noted, Chenaux’s gently yearning voice resembles Chet Baker’s. Yet if this is jazz, it’s a thoroughly modern, electronic version. Rather than using a conventional kit, the trio’s percussionist Philippe Melanson triggers samples. Working without a bass, they’ve rethought the jazz trio lineup. The group plays around with Chenaux’s originals as though they were reworking standards. His lyrics stick to matters of the heart, but the performances push the subject toward science fiction.

On the trio’s latest album, Delights of My Life (Murailles Music), Chenaux’s production brings together his guitar and Ryan Driver’s Wurlitzer organ as its core, with electronics worked in at the edges. “Light Can Be Low” ties organ chords and spacey electronics together in counterpoint. Similarly, Chenaux plays a slow, ambling electric guitar lead through “Delights of My Life,” while synthesizers wheeze around it. Even at the group’s most traditional, the drums never sound live. “This Ain’t Life” keeps percussion as minimal as it can get while still pushing forward. Melanson avoids settling into a groove, letting Driver vamp around him. He also sticks to soft tones, manipulating samples of hi-hats, maracas, and woodblocks.

Melanson and Driver’s effects pedals board looks to the more experimental reaches of jazz fusion, especially early ’70s Herbie Hancock. Wah-wah and ring modulation deliver the sound of a swarm of bees buzzing angrily. The trio format lets each instrument, including Chenaux’s voice, weave around the others. Throughout, a productive tension between songcraft and extended improvisation persists, pushing at Chenaux’s compositions without ever abandoning their structure.

— Steve Erickson

Rock

What’s his name? Ringo! And he’s back with a new EP, Crooked Boy (UMe). Untroubled by the restless artistic ambition that haunted Saints John, Paul, and George, the drummer is here to entertain you — and himself — with nothing left to prove.

What’s his name? Ringo! And he’s back with a new EP, Crooked Boy (UMe). Untroubled by the restless artistic ambition that haunted Saints John, Paul, and George, the drummer is here to entertain you — and himself — with nothing left to prove.

Crooked Boy is a collaboration with established songwriter Linda Perry. Ringo usually has a large group, but here it’s just Ringo, Perry on guitar/bass/organ/background vocals, Josh Goosh on guitar, and Strokes lead guitarist Nick Valensi. Perry produced and did all the writing.

Like Paul, Ringo shows his age when he strains for the occasional high notes, and there’s a certain wobble in his warble. But like Paul, his rock authority is hard-earned, and there’s a gravitas in his voice now that shadows his high-spirited optimism.

Ringo makes a still-not-retiring announcement in “February Sky,” stating he’s ready to “start a revolution in these dark days.” “Adeline” is the catchy, fun song that Ringo always does so well. The lyrics are in the “All You Need Is Love” category, although they’re grounded in the real world with real people: “Love is good, but not all the time/But everybody can be safe.” The grandfatherly Ringo is no longer in an octopus’s garden or sealed off in a fantasy yellow submarine.

“Gonna Need Someone” is the up-tempo rocker with a call-and-response chorus to rouse the live audience. Perry, equally skilled in composing R&B and pop, is clearly also in command of the classic rock format.

“Crooked Boy” will please the Beatles fans, not only with the callouts in the lyrics, but also with some of Ringo’s trademark drum fills. Ringo’s nostalgia is from the perspective of someone at peace with where he is. This is a gratefully self-congratulatory look backward, free of too much troublesome introspection or painful insight. There’s a simple, consistent, honest, and quietly decent philosophy that has defined Ringo for 60 years now: “I speak of love, I speak of peace/It’s what I believe/And what I keep on fighting for.”

Treasure Ringo, and Paul, while they’re still with us. We’ll never see their likes again.

— Allen Michie

Books

One of today’s most popular romance authors, Emily Henry proves she is still at the top of her crowd-pleasing game with Funny Story (Penguin Publishing Group, 400 pages), another of her entertaining romantic comedies with charismatic leads and a heartfelt plot.

One of today’s most popular romance authors, Emily Henry proves she is still at the top of her crowd-pleasing game with Funny Story (Penguin Publishing Group, 400 pages), another of her entertaining romantic comedies with charismatic leads and a heartfelt plot.

Daphne Vincent has moved back to the lakeside hometown of her soon-to-be husband, Peter. She has a rewarding job at the library and is living in a big house. The young woman adores order; she relies on her detailed calendar and hates surprises. The setup gives Daphne what she has always searched for — stability. However, the morning after Peter comes back from his bachelor party, her once perfectly reliable fiancé changes everything. The guy cancels the wedding and then, shockingly, gets together with his easy-going best friend, Petra.

Daphne can’t afford to stay in the house and has nowhere to go. But Petra’s ex-boyfriend, Miles, the woman’s complete opposite, has an extra room in his messy apartment. After Daphne receives Peter and Petra’s wedding invitation, the guy has the nerve to call her. She lies to him about having a new boyfriend, Miles, so she will be coming plus-one to Peter’s wedding. Plenty of predictable romantic moments ensue after that decision, but Henry is not content with those: she gives her characters depth by exploring complicated family relationships.

Funny Story doesn’t merely rely on the main couple’s chemistry — though there is plenty of it. The thrust of this story is how its characters confront, and eventually accept, good, bad, and unpleasant things about themselves and others around them. Being with someone else has always been Daphne’s focus; she has always been a part of a we (a couple). She gradually learns how to make rewarding choices for herself, ranging from who to be friends with to what city to live in.

Henry knows how to blend heartbreak and humor — this is a feel-good narrative that doesn’t become coyly sentimental. Funny Story is about how real happiness is about accepting the unpredictable, of looking beyond, or even embracing, the faults of others.

— Ana Peres

Andrej Nikolaidis’s Anomaly (Peirene Press, 138 pages), translated from Montenegrin by Will Firth, caught my attention for a number of good reasons. The writer is a fearless critic of the illiberal turn politics and culture are taking in a country that’s flirting with pro-Russian authoritarianism. (Check out his columns in the Guardian.) On top of that, Nikolaidis is putting himself in danger when he dares to speak out. PEN International reported that on March 3, “organizers of the Herceg Novi carnival burned an effigy of Andrej Nikolaidis, amidst chants denigrating his mixed ethnicity and association with Montenegrin literature. The incident generated wide coverage in Montenegro and the broader region, with civil society and academics fearing his targeting is reminiscent of historical acts of book burnings.”

Andrej Nikolaidis’s Anomaly (Peirene Press, 138 pages), translated from Montenegrin by Will Firth, caught my attention for a number of good reasons. The writer is a fearless critic of the illiberal turn politics and culture are taking in a country that’s flirting with pro-Russian authoritarianism. (Check out his columns in the Guardian.) On top of that, Nikolaidis is putting himself in danger when he dares to speak out. PEN International reported that on March 3, “organizers of the Herceg Novi carnival burned an effigy of Andrej Nikolaidis, amidst chants denigrating his mixed ethnicity and association with Montenegrin literature. The incident generated wide coverage in Montenegro and the broader region, with civil society and academics fearing his targeting is reminiscent of historical acts of book burnings.”

Add to that fortitude Nikolaidis’s enthusiasm for the bleak grotesquerie of hellion Thomas Bernhard, and you have a fiction writer of interest, at least for those of us who like their narratives on the acidic side. This entertaining sci-fi volume offers, via a series of short episodes, an absurdist depiction of the end of the world by way of Biblical overkill: not the waterlogged whimper of global climate catastrophe, but rivers of blood rampaging through the streets, woolly mammoths falling on people’s heads, and a pterodactyl or two flying overhead.

Not much is made of extinction: Nikolaidis’s characters go about their chaotic lives until they are suddenly and senselessly cut off, often in the last paragraph. Sometimes the instrument of death comes from another era (as the end approaches, time collapses). The spotlit victims include the monstrous (a gangster on a killing spree), the vulnerable (a send-up of Hans Christian Andersen’s Little Match Girl with an amusing shout-out to Ambrose Bierce), and the earnest (a pedant in the Alps searches for a mysterious musical composition of apocalyptic appeal). Nikolaidis strikes me as closer to the heartbroken Kurt Vonnegut than the nihilistic Bernhard. His non-fable fables (you can almost hear Anomaly‘s impish narrator mutter “… So it goes”) reflect a savagely bruised humanism: “If God really loved you, he’d do one thing: protect you from your desires.”

— Bill Marx

“Blood, vermillion, crimson, peony, columbine, peach blossom, or heather reds; clove or gladiolus purples; yellows associated with marigold, saffron, and lion’s fur; cheerful or meadow greens; heavenly sky blue; and leaden or donkey-black gray.” This list, compiled from 14th-century European documents of woolen fabric colors, appears early in Anne Varichon’s Color Charts: A History (translated by Kate Deimling, Princeton University Press, 264 pages). The fanciful terms, which seem rooted in the natural or agricultural world, begin a thread of poetic color names that run throughout the book, as if the attempts to define, scientifically organize, and market color over the centuries inevitably fall back on the figurative and evocative.

“Blood, vermillion, crimson, peony, columbine, peach blossom, or heather reds; clove or gladiolus purples; yellows associated with marigold, saffron, and lion’s fur; cheerful or meadow greens; heavenly sky blue; and leaden or donkey-black gray.” This list, compiled from 14th-century European documents of woolen fabric colors, appears early in Anne Varichon’s Color Charts: A History (translated by Kate Deimling, Princeton University Press, 264 pages). The fanciful terms, which seem rooted in the natural or agricultural world, begin a thread of poetic color names that run throughout the book, as if the attempts to define, scientifically organize, and market color over the centuries inevitably fall back on the figurative and evocative.

You might conclude from its title that the book’s content is esoteric or even trivial. You would be wrong. Using splendid, rare examples mostly never before published, Varichon weaves her narratives through the Enlightenment, the rise of Western industrialized society, the development of chemistry, modern textile manufacturing, the invention and exploitation of aniline dyes, the rise of mass-produced cosmetics, the democratization of taste and marketing via the department store, seasonally-based fashions, a revolution in art thanks to prepared and stabilized pigments.

Along the way, she quotes pioneering chemists and semiologists Umberto Eco and Michel Foucault, explains elaborate systems for classifying and comparing color, and introduces color charts for every conceivable material, from watercolors, silk dyes, and lipstick to artificial teeth. Charts range from a 17th-century manuscript by the Dutch painter A. Boogert with 2100 watercolor samples in a “perfect” structure in which each page “evokes the gardens of medieval monasteries” to a 24-panel, 2.16 meter wide “leporello” classifying 360 samples of dyed silk thread.

The writing is graceful and witty, the illustrations rich and in full color, and the concept delightful and strikingly original.

— Peter Walsh

Visual Art

Mural on Simons Theatre at New England Aquarium in Boston by Shepard Fairey, 2021. Photo by Jon Furlong of Shepard Fairey Studios

Completed in August of 2021 during Covid, the stunning 60-foot-high mural set on a side wall at the Simons Theatre of the New England Aquarium graphically highlights an endangered North Atlantic right whale and a globe. The images are accompanied by text that reads “Protect the blue planet,” “a vital & vibrant ocean for all” and “one ocean — one people.” The visual was created by internationally renowned artist Shepard Fairey.

Considered the second most famous street artist in the world after the UK’s Banksy, Shepard Fairey has become renowned for blending visually stylized street art, illustration, and graphic design with occasionally ironic, as well as sometimes iconic, social and political imagery. Educated at the Rhode Island School of Design in Illustration, he was still in attendance in Providence in 1989 when he designed and distributed “Andre the Giant Has a Posse” a street art sticker campaign that quickly went viral.

One of Fairey’s most famous pieces is the Barack Obama “Hope” poster, designed for the 2008 US presidential election. The striking image came to represent Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign. It is a stylized stencil portrait of Obama in solid red, beige, and (light and dark) blue, with either the word “progress,” “hope,” or “change,” set below.

Fairey’s creative body of work includes murals, T-shirts, posters, prints, and publication cover art. Most of what he produces deals with notable political and environmental issues and events. It should not be a surprise that Fairey has invited controversy: copyright infringement, arrests for graffiti and public vandalism. There have even been issues raised about his more well-heeled clients, including major corporate and national retailers. Fairey’s response to his assorted critics about his mainstream work is to explain that these paid commissions allow him to donate his firm’s creative time and effort to supporting a range of important social, political, and environmental causes — like the Boston Sea Walls project.

The Simons Theatre mural is one of a series of 14 public Boston-area murals for Sea Walls: Artists for Oceans, a program of the PangeaSeed Foundation, which is dedicated to raising awareness about ecological sustainability, including the importance of the health of the oceans, a major contributor to the overall well being of our planet. The local coordinating host for the mural was Boston HarborArts.

— Mark Favermann

Tagged: "Color Charts: A History", "Delights of My Life", "Funny Story", "New Moon", "One More Lifetime", Allen Michie, Ana Peres, Anne Varichon, Breve, Calliope’s Call, Crooked Boy, Emily Henry, Eric Chenaux, Eric Chenaux trio, Euclid Quartet, Evangelina Leontis, Golda Schultz, JJ Penna, John Hurlbut, Jorma Kaukonen, Megan Roth, Mozart, Pomme, Randall Goosby, Ringo Starr, Roots (Deluxe Edition), Saisons, Scott McLennan, Shepard Fairey, Simons Theatre of the New England Aquarium, Steve Erickson