Classical Album Reviews: Violinists Frank Peter Zimmermann and James Ehnes play Stravinsky

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Franz Peter Zimmermann’s rendition of Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto overflows with style and character; James Ehnes’s version is generally warmer and more relaxed, though it doesn’t lack for rhythmic zip

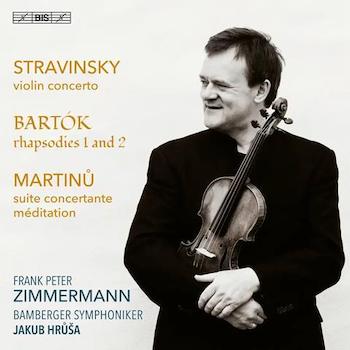

Franz Peter Zimmermann’s stage presence is often focused and no-nonsense. But such outward seriousness belies a musician whose playing overflows with style and character. Both of those qualities abound in his new recording of music for solo violin and orchestra with the Bamberger Symphoniker and Jakub Hrůša.

Franz Peter Zimmermann’s stage presence is often focused and no-nonsense. But such outward seriousness belies a musician whose playing overflows with style and character. Both of those qualities abound in his new recording of music for solo violin and orchestra with the Bamberger Symphoniker and Jakub Hrůša.

The album’s most familiar item is Igor Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto. Composed in 1931, the twenty-minute-long work distills the composer’s neo-Classical idiom to its essence. Zimmermann’s performance here is invitingly dry and droll.

His command of the music’s exacting rhythms is total (especially in the outer movements), but there’s also a warmth and fervency to the score’s lyrical flights that proves compelling. This is most true in the first Aria, which Zimmermann plays with almost surprising urgency, and the finale, in which the music’s skittish playfulness never comes at the cost of beauty of the line.

Hrůša and the Bambergers are vital accompanists, teasing out all sorts of details in the Concerto’s transparent instrumentation (the first movement’s growling bassoon figure emerges quite humorously) while neatly matching Zimmermann’s articulations and phrasings.

The pairing are likewise sympathetic advocates for Bohuslav Martinů’s Suite Concertante. A four-movement effort from 1944, the work is a concerto in all but name, though its effectiveness is periodically hampered by a stuffy approach to form.

Nevertheless, Zimmermann dispatches the solo part energetically. He gets its Aria to soar and mines the playful moments in the opening Toccata and concluding Rondo for all they’re worth. Ditto for the genuinely playful episodes in the Scherzo.

The Bambergers’ accompaniments are as lean and discreet in the Suite as they are lush and serene in Martinů’s short Meditation, which closes the disc.

They’re also thoroughly modish in both of Béla Bartók’s Rhapsodies. These evocations of traditional gypsy violin music don’t turn up often in concert; one wonders why given how brilliantly they’re served up here.

In both scores (written in the 1920 and orchestrated in the ‘30s), the Bambergers bring kaleidoscopic colors to their accompaniments as well a swaggering, exuberant sense of rhythmic release. Zimmermann is typically in his element, too, imbuing the First Rhapsody’s double-stops with remarkable clarity and the Second’s improvisatory, dance-like phrases with vigor.

In his new recording of Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto, James Ehnes takes a slightly different approach to Zimmermann. His reading, in which the violinist is joined by the BBC Philharmonic and Sir Andrew Davis, is generally warmer and more relaxed.

In his new recording of Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto, James Ehnes takes a slightly different approach to Zimmermann. His reading, in which the violinist is joined by the BBC Philharmonic and Sir Andrew Davis, is generally warmer and more relaxed.

It’s still got plenty of rhythmic zip, though, particularly in the outer movements. Throughout, his voicings are also astonishingly clean: Ehnes’ articulation the triplets in the double-stops during the Capriccio’s coda are spot-on. And he has no trouble getting this music to sing, as one can hear in his realization of the gorgeous middle section of the second Aria.

Davis presides over a fine accompaniment, as well. Balances between soloist and orchestra are always good, textures lean. The woodwind contributions in the first Aria are notable for their lovely blend, while the capering spirit of the finale emerges with brio.

The orchestra also shines in the album’s remaining selections.

Their performances of the Scherzo a la russe and the Suites Nos. 1 and 2 (orchestrations of short piano pieces Stravinsky wrote in the early-‘20s) brim with personality. Particularly striking are a pair of movements from the second set: the pungent Marche, which seems to recall Petrushka, and the fragmented, cheeky Valse.

The Philharmonic’s account of Apollon Musagète, Stravinsky’s 1928 ballet with George Balanchine, comes across impressively, too. There’s a shapely fluency to Davis’s approach to this music that works quite well: the Prologue flows sonorously, the Pas d’action’s counterpoint always speaks, and the score’s echoes of Tchaikovsky (especially in the Variations de Polymnie and Pas de deux) unfold radiantly.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Bamberger Symphoniker, Bis, Chandos, Franz Peter Zimmermann, Jakub Hrůša, James Ehnes