Classical Album Reviews: “A Lionel Tertis Celebration” and “Laws of Solitude”

By Jonathan Blumhofer

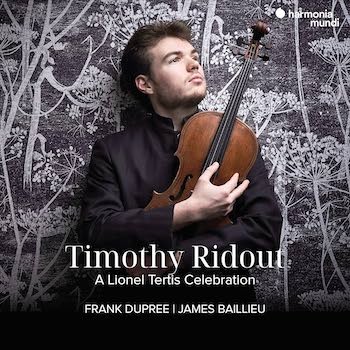

Violist Timothy Ridout’s new double-album A Lionel Tertis Celebration is heartily recommended; soprano Asmik Grigorian’s Laws of Solitude not so much.

It’s been nearly fifty years since violist Lionel Tertis died at the age of 98 and, while his discography is somewhat obscure, his influence on the instrument remains significant. Timothy Ridout’s new double-album, A Lionel Tertis Celebration, marks the great man’s legacy with a survey of pieces Tertis either championed or arranged.

Given that Tertis is largely held responsible for elevating the viola as a solo instrument, there’s a good bit to go on. And, though it’s not a comprehensive survey, Ridout’s program is invitingly laid out with a number of short pieces bracketed by two big sonatas, York Bowen’s First and Rebecca Clarke’s only one.

The Bowen is a magnificent work that receives a suitably grand performance from Ridout and pianist Frank Dupree. This is music of bold extremes and the duo simply intuit where it needs to go and how it ought to get there. Accordingly, for sweep, character, tone, and intensity, theirs is a reading that leaves little to be desired, either in the score’s soulful turns (the dreamy, hymn-like middle movement) or electrifying ones (the lusty finale).

Clarke’s somewhat better-known effort receives similarly sumptuous treatment. Its opening Impetuoso is fittingly impassioned and luminous while the Vivace sparkles. In the Adagio, Ridout and pianist James Baillieu balance soulful expressivity with breathtaking unanimity of articulations; the results are beautifully, compellingly shaped.

The smaller works range from memorable to curious.

Among the former are a pair of Tertis transcriptions (of Brahms’s Minnelied and Schumann’s Romance in F-sharp, respectively), as well as William Wolstenholme’s Allegretto in E-flat, Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Six Studies on English Folksongs, and a couple viola arrangements of Fritz Kreisler violin works. There’s also luminous setting of Mendelssohn’s E-major Song without Words (Op. 19 no. 1), replete with fluid double stops.

If not all the remaining items are so stirring — Tertis’s adaptation of the first movement of Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata for viola and piano is the definition of a novelty one probably won’t return to with frequency — they’re nicely varied (Gabriel Fauré, Eric Coates, and John Ireland, among others, are all represented) and smartly played.

The whole effort adds up to an appealing, beautifully executed, and warmly recorded commemoration of Tertis and his instrument. More than that, though, it cements Ridout’s position as one of preeminent violists of the day. Heartily recommended

Soprano Asmik Grigorian’s Laws of Solitude is a peculiar release, and not just for its enigmatic title or the algebraic doodles that dot its booklet. More than those, the organization of its content is singular: Richard Strauss’s Four Last Songs sung not once, but twice – first with orchestra, the next time with piano accompaniment.

Why go this route? Because, as Grigorian writes, “each [version] require different colors — even if they are the same piece.”

Funny she should mention color because, particularly in the performance with orchestra, that’s largely what’s missing from the vocal part. Instead, what emerges is monochrome and bit chilly; this is not Gundula Janowitz’s and Jessye Norman’s Four Last Songs.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing. The music can certainly take a fresh approach and Grigorian’s instrument is never less than impressive for intonation and projection; she doesn’t force any of the notes.

But neither does she settle into these songs in ways that prove particularly satisfying. One wants more magic in “September” and “Beim Schlafengehen” than the Armenian-Lithuanian soprano manages to conjure. Only in the closing “Im Abendrot” does Grigorian really manage to soar.

For their part, the Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France and conductor Mikko Franck supply lucid accompaniments, their playing always moving purposefully (and rather unexpectedly so in “Frühling”) and lean.

Grigorian’s second rendition of the Songs with pianist Markus Hinterhäuser is somewhat more successful. Their broader approach to the music gives the singer more room to let her sound blossom (in this iteration, “Beim Schlafengehen” proves altogether more satisfying) and there’s a bit more flexibility to shape phrases this time around.

That said, some of the duo’s tempo choices are eyebrow-raising: “September” and “Im Abendrot” inexplicably clock it more than ninety seconds longer than in the orchestral performance. The former often feels like it’s about to stop in its tracks; its closing section seems to lose momentum by the beat. And the same issues of frosty tone encountered with the orchestra aren’t completely resolved here.

Ultimately, then, Laws of Solitude, though unique in conception, doesn’t quite justify itself. Unusual? Yes. Boasting some striking individual performances? You bet. Competitive with the better and best recordings of this fare? No.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.