Visual Arts Review: “A Female Landscape and the Abstract Gesture” — Please Observe Carefully

By Kathleen Stone

This is a small show, only 18 pieces, but each drew me into thinking about what I was seeing and, simultaneously, how the artist made it.

A Female Landscape and the Abstract Gesture, at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute in Byerly Hall, 8 Garden Street. Cambridge. Visitors are asked to register in advance on the Harvard Radcliffe Institute website.

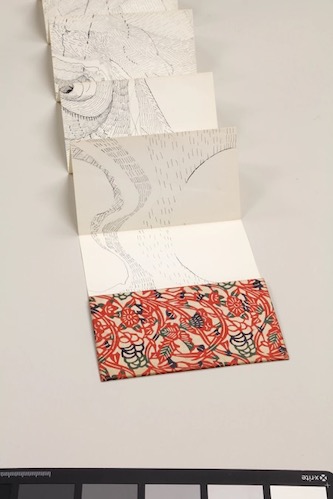

Mildred Thompson, A Female Landscape, 1977, detail. Artist book. Photo: Mike Jensen

When we come upon a piece of abstract art, the usual first instinct is to sort out what we are seeing. Are the colors and shapes appealing? Can we identify an object or a person? Next, we might move on to think about the medium and how it was made. What physical actions were involved? Do we see evidence of the artistic process? When evidence of the process is a prominent part of the work itself, we end up thinking two things at once. That, at least, was my experience while visiting an exhibit at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute. It’s a small show, only 18 pieces, but each drew me into thinking about what I was seeing and, simultaneously, how the artist made it. In other words, both optic and haptic perceptions were at work.

Four artists are represented: Maren Hassinger, Howardena Pindell, Liliane Porter and Mildred Thompson. The work is abstract, mainly from the 1970s and 80s, a mix of constructions, prints, drawings, and one watercolor painting.

The exhibit draws its title, A Female Landscape and the Abstract Gesture, from a piece by Mildred Thompson. Described as an accordion fold book, it’s a stretch of paper, at least six feet long, folded to resemble an accordion. On the paper Thompson has inked thousands of hatch marks to create a sense of volume and shape. Some shapes are recognizable as parts of the female anatomy, others merely suggestive. Overall, we are left with the impression of a womanly rolling landscape with a ravine here and a pasture there, all set amid constantly undulating hills. The magnitude and fineness of the hatch marks leads us to imagine the artist at work, painstakingly deploying her pen, for more hours than we can count.

The label tells us that book was a gift to Audre Lorde and preserved as part of her papers at Spelman College. Curious about the connection to Lorde, I found an article in ArtNews describing Thompson and Lorde as having been lovers for a time and contributors to a collaborative sketchbook titled Journey Stones: Love Poems. In general, the exhibit provides little in the way of biographical information about the artists, or about the context in which they worked. To appreciate the art, viewers must carefully observe the work itself.

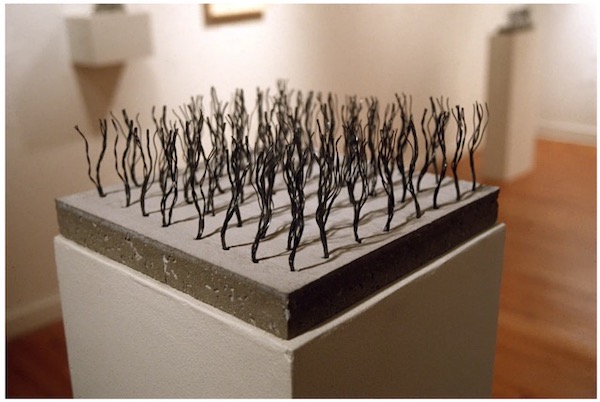

Maren Hassinger, Garden, 1985, detail. Concrete and wire rope, 4 x 12 x 12 inches. Photo: Courtesy of the artist and Susan Inglett Gallery, New York

Thompson’s other work includes constructions made of wooden strips nailed to a backing, what she called “wood pictures.” The strips create linear patterns, but design is less important than the pictures’ constructed nature. Nails and wood grain are obvious, as are gaps between the strips. Some strips bear a stamp that identifies the type of wood and its moisture content, information that is useful to a builder choosing lumber for a project. Thompson reminds us that she is a builder of art.

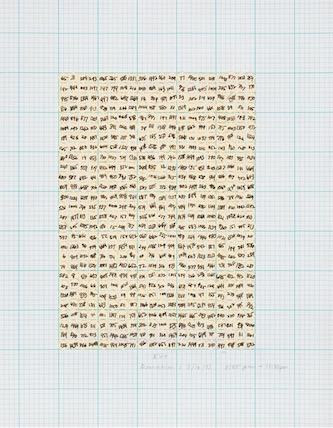

Howardena Pindell, Duration: 5/16/73, 1973. Ink on paper collage, 11 x 8 1/2 inches. Photo: Christopher Burke Studios/ShootArt

Liliane Porter has three prints in the show, each augmented with a piece of string or yarn. In her etching titled Stitch, we see a piece of black yarn poking through the paper, under a printed line. The yarn looks almost like a continuation of the line, but it’s not. It’s separate and three-dimensional, giving a trompe l’oeil effect that makes us conscious of the artist’s wit as she carefully pulls the yarn through a hole in the paper. Hook, a screen print of a round metal hook and its shadow, is an even more intriguing work of trompe l’oeil. Porter has knotted a piece of black string and laid it on top of the printed hook so that it looks as though the string wraps around the metal. The dual layers — flat printed image and three-dimensional knot — keep us suspended between what we think we see and what we know must be.

Numbers can also tell us about artistic process. In a collage titled Duration: 5-16-73, Howardena Pindell uses numbers in two ways. She meticulously writes numbers on small paper circles and affixes the circles to graph paper. The numbers are out of sequence but, with thirty-five squares, each with sixteen circles, we can determine we are looking at 560 circles. How long did she spend on this project? Again, numbers tell us. A pencil notation reads “8:55 pm – 11:33 pm,” an intense 158 minutes of artistic production.

To create her Garden, Maren Hassinger planted strands of wire rope in concrete. The same type of rope inspires the abstract shapes in her woodblock prints. The clumps of rope look as though they are being blown by the wind, or bending toward the sun. Here, the artist has manipulated manufactured material to simulate nature. Art imitates life, and we find ourselves thinking simultaneously about what we are seeing and how it was made.

The exhibit was curated by Chassidy Winestock, a PhD candidate in Harvard’s Department of History of Art and Architecture, whose dissertation covers these four artists.

Kathleen Stone is the author of They Called Us Girls: Stories of Female Ambition from Suffrage to Mad Men, an exploration of the lives and careers of women who defied narrow, gender-based expectations in the mid-20th century. Her website is kathleencstone.com.

Tagged: A Female Landscape and the Abstract Gesture, Howardena Pindell, Liliane Porter, Maren Hassinger