Concert Review: Cat Power — Sharing Life on the Tightrope That Is Live Performance

By Paul Robicheau

Cat Power transformed Dylan’s songs across a 90-minute set that appeared organically studied, slightly unsettled, and ultimately sublime, as the singer rode the arc from a shadowy “She Belongs to Me” to an exultant “Like a Rolling Stone.”

Bob Dylan’s 1966 “Royal Albert Hall” concert enthralls as a landmark in musical history. Long bootlegged before its official release in 1998, the show — actually recorded in Manchester several days before Dylan closed a controversial UK tour at London’s storied hall — captured the singer-songwriter at the height of his creative powers during a transition from folk paragon to electrified pariah.

The show began with a well-received solo acoustic stretch, then mixed reactions when he brought out musicians who (apart from a fill-in drummer) later became the Band. “Judas!” someone infamously yelled before the final song, prompting Dylan to snap “You’re a liar” and goad his rocking ensemble to play louder.

Times have changed. Cat Power — the nom de plume of singer Chan Marshall — faced a different dynamic in recording her version of the entire Dylan set at the actual Royal Albert Hall, then taking it on tour. On Saturday at Medford’s Chevalier Theatre, Cat Power transformed those songs across a 90-minute set that appeared organically studied, slightly unsettled, and ultimately sublime, as the singer rode the arc from a shadowy “She Belongs to Me” to an exultant “Like a Rolling Stone.”

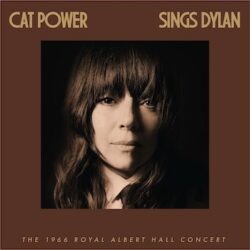

How does it feel to be on your own, singing only that iconic set for an expectant full house? Only Marshall truly knows. She has the material down cold since last year’s Cat Power Sings Dylan: The 1966 Royal Albert Hall Concert. And over a 30-year career, she’s made a few other cover albums as a formidable interpreter. Her original albums shouldn’t be overlooked either: the soul-soaked The Greatest was one of 2006’s best. Yet her struggles with mental health grew evident at that time (she couldn’t get through songs during a solo show at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts). She doesn’t allow photographers, though she’s not as militant about it as Dylan.

Marshall could be forgiven for feeling self-conscious when she began Saturday’s concert as the center of attention, sparsely accompanied by Henry Munson on acoustic guitar and pianist Aaron Embry on occasional harmonica. In an all-black suit with a loose necktie hanging to her bustier, her hair cropped short, Marshall initially sounded more tentative than her mesmerizing acoustic turn on the live record, but she warmed up as a vocalist by the second song, “Fourth Time Around.” Like Dylan, she elongated certain words and varied their tempos, but did so with her own hazily phrased delivery, casually changing a few words along the way.

She managed all that despite appearing distracted during early songs, signaling to the sidelines to adjust the sound mix in her monitors and seeming unsure what to do with her hands. At times, she pressed one hand against her waist like a rudder, but when she sang “The fiddler now steps to the road” in “Visions of Johanna,” the singer motioned as if she were playing a violin. The poetic sprawl of that song and a 13-minute “Desolation Row” (where Marshall rested one hand on the stand beside her during Embry’s mournful harmonica break) came close to casting a somnolent spell, due in part to Munson’s soft, simple strumming.

Finally, Marshall took the mic from its stand to pump up “Just Like a Woman,” striding forward in stiletto heels to charm the front rows. And “Mr. Tambourine Man” floated as a revelation. “I’m ready to go anywhere, I’m ready to fade,” she sang over Munson’s delicate fingerpicking, and house lights at the edges of the theater suddenly went dark, accenting focus on the primitively backlit stage.

With no break, the rest of her six-piece band (the same musicians from her Albert Hall album, save the substitution of past collaborator Adeline Jasso on guitar) filed out. “Tell Me, Momma” didn’t introduce the messy snarl of Dylan’s version but sure took the set’s energy to a higher level. Marshall even turned into a practical social director. She pointed to Munson for a twangy electric solo (as if he needed a cue) and called out that there were two empty seats in the front row to be filled.

The band gave a garagey Memphis soul feel to “I Don’t Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met)” as the singer busted a brief dance move and shrugged to the seated audience. A lone dancer picked up the hint during “Baby, Let Me Follow You Down” and when security asked her to clear the aisle, Marshall appeared disappointed, quipping, “That’s my niece. She doesn’t get out much.”

Cat Power. Photo: Inez Vinoodh

“Leopard Skin Pill Box Hat” kicked in with loping bass over a swinging beat, and when Marshall thought the guitar solo wasn’t cutting through, she walked over to Munson’s amp and turned it up. The band added just the right playfully ominous mood to “Ballad of a Thin Man,” underscored by swirling organ. The Georgia-born Marshall betrayed her Southern drawl on the word “understand” and tackled the chorus “Something is happening here, but you don’t know what it is. Do you, Mister Jones?” with delight.

“I’m honored to be here as a career choice,” Marshall said before the final song. “It’s more difficult than other free rides.” She thanked the crowd and Dylan, then dedicated the show to Dexter Romweber, the founder of the Flat Duo Jets who died last week at 57 and was one of Marshall’s indie-rock inspirations. Following a band introduction, yes, some smart aleck toward the back of the theater shouted “Judas!” and was ignored as Cat Power roared into “Like a Rolling Stone.”

“Do you want to make a de-al?” Marshall sang in a husky howl, fans not invisible now as they danced in the front aisles. “Keep the faith,” she said among other clichéd platitudes to the crowd’s parting ovation. Yet she appeared genuinely touched, having shared life on the tightrope that is live performance.

Paul Robicheau served more than 20 years as contributing editor for music at the Improper Bostonian in addition to writing and photography for the Boston Globe, Rolling Stone, and many other publications. He was also the founding arts editor of Boston Metro.

Tagged: Cat Power, Cat Power Sings Dylan: The 1966 Royal Albert Hall Concert, Chan Marshall