Arts Feature: Recommended Books, 2023

Compiled by Bill Marx

An eclectic round-up of the favorite books of the year from our critics.

Roberta Silman

FICTION:

House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng

House of Doors by Tan Twan Eng

Natural History by Andrea Barrett

We Must Not Think of Ourselves by Lauren Grodstein

At the Edge of the Woods by Kathryn Bromwich

Small Things Like These by Claire Keegan

Norman Rules Do Not Apply by Kate Atkinson

NON FICTION:

Prequel by Rachel Maddow

Democracy Awakening by Heather Cox Richardson

Fearless Women: Feminist Patriots from Abigail Adams to Beyoncé by Elizabeth Cobbs

Matt Hanson

Historical novels can be tricky in the sense that you’re never sure if you’re getting the real deal or not. Tom Piazza’s new novel, The Auburn Conference, dreams up the greatest literary conference that never happened. It’s 1883, with the specter of the Civil War still hanging over the country. A bunch of esteemed and essential writers come to a small school in upstate New York to discuss the meaning of writing, what it means to be an American, and even mix it up about each other’s work. The attendees include Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, Frederick Douglass, Mark Twain, Harriet Beecher Stowe, as well as two fictional writers, a popular writer of bodice rippers, and a smouldering Confederate general (available for a visit from a thinly veiled Emily Dickinson). Some might expect that such a gathering of eminences would be boring and wonky. Not at all– the novel’s secret weapon is its humor. In fact, at times pithy congregation strays into the realm of campus comedy. And what’s more, the narrative ends on a quavering note of hope for our frayed republic.

Historical novels can be tricky in the sense that you’re never sure if you’re getting the real deal or not. Tom Piazza’s new novel, The Auburn Conference, dreams up the greatest literary conference that never happened. It’s 1883, with the specter of the Civil War still hanging over the country. A bunch of esteemed and essential writers come to a small school in upstate New York to discuss the meaning of writing, what it means to be an American, and even mix it up about each other’s work. The attendees include Walt Whitman, Herman Melville, Frederick Douglass, Mark Twain, Harriet Beecher Stowe, as well as two fictional writers, a popular writer of bodice rippers, and a smouldering Confederate general (available for a visit from a thinly veiled Emily Dickinson). Some might expect that such a gathering of eminences would be boring and wonky. Not at all– the novel’s secret weapon is its humor. In fact, at times pithy congregation strays into the realm of campus comedy. And what’s more, the narrative ends on a quavering note of hope for our frayed republic.

Steve Erickson’s American Stutter technically came out last year, but that doesn’t affect the book’s relevance one bit. It’s a unique kind of personal/political/poetic meditation on what it’s like to have been alive during our turbulent times. He writes about living during the pandemic, a painful divorce, and the ambient buzz of dread that comes with the Trump-saturated political zeitgeist. I was really moved by the way he subtly juxtaposed the personal and the political — it’s not like his private angst turns into marching orders, it’s more that we can see the ripples of the collective unconscious as they upset a smart, decent, worried man who is quietly singing his worried song.

Roberta Silman’s new novel Summer Lightning began the year for me and it makes for a nice pairing with Erickson’s personal nonfiction chronicle of a plague year. Her book is a family chronicle that almost spans an entire century; the plot explores the immigrant experience, historical guilt, the changing of the guard of generations, and the sustaining power of family. This is fiction that reminds us that, even though we’re living in the present, we are nevertheless imbued with the past.

Allen Michie

Barbara Kingsolver, Demon Copperhead (Harper)

Barbara Kingsolver, Demon Copperhead (Harper)

Reading this novel alongside Charles Dickens’s David Copperfield made it clear that Kingsolver is much more than a clever adapter of someone else’s story and characters. She saw deeply into what Dickens meant to communicate about the conflicts of his times and how these crises destroyed some of his characters and provided opportunities for others to rebuild. She convincingly transported those dramas of moral testing to Appalachia in our own troubled times.

Maria Golia, Ornette Coleman: The Territory and the Adventure (Reaktion)

As I wrote in a review, “Golia writes with informed affection for Coleman the man, but even more powerfully, she writes of how Coleman’s drive and creativity was formed through his distinctive path through American cultural history. When Coleman says that harmolodics means ‘Harmony, melody, speed, rhythm, time and phrases all have equal position in the results that come from the placing and spacing of ideas,’ you may not always be clear on how that manifests in his sometimes difficult music, but Golia shows us how a harmolodic imagination like his was, for a time, both possible and necessary.”

Ed Meek

Recommended Nonfiction Books 2023

After Black Lives Matter by Cedric Johnson

The Black Lives Matter movement raised many salient political issues but failed to resolve them. Cedric Johnson brilliantly delves into how American capitalism, combined with racism, is at the root of many of our problems. The author draws on Karl Marx to support his argument that to reduce crime, violence, poverty, and racism, we must address inequity by working together to overcome class divisions.

Status and Culture by W. David Marx

David Marx explores the role that status plays in determining nearly every decision that we make in work and play. After reading this book you will take a fresh (perhaps discomforting) look at what is going on in family get-togethers. You will have a better idea about what those Allbirds say about you and and why you prefer Starbucks or Dunkin.

Poverty, by America by Matthew Desmond

Desmond writes with authority about poverty from the viewpoint of a scholar who has lived among the poorest Americans in cities and trailer parks. He takes a deep dive into the plight of the 40 million Americans who live in poverty. (It is a number that has barely budged in 50 years.). He also explains how our policies subsidize the middle class and the rich at the expense of the poor. Art Fuse review

Vincent Czyz

Boundless as the Sky by Dawn Raffel (Sagging Meniscus)

Boundless as the Sky by Dawn Raffel is one of those books a small press can wear around its neck like a charm to drive the publishing conglomerates — New York’s Big Five — mad with envy. A slim volume divided into two parts, the first 62 pages read as though Italo Calvino’s ghost had decided to continue Invisible Cities with a feminist edge; it is a series of vignettes in conversation with Calvino’s book and, if anything, more beautifully written. Part I has the feel of a mosaic of prose poems that has accreted around the theme of the city. The second half is a novella that hearkens back to sections in the first half (these too, in other words, are in conversation). Here we find some good old-fashioned storytelling and a cast of characters whose destinies intersect on a single day at the 1933 World’s Fair in Chicago. What makes this book such a rare find is that it is both high art and hard to put down.

The Last Judgment by Robert Steiner (Spuyten Duyvil)

Robert Steiner, the author of 10 novels as well as a book of art criticism, was a consummate stylist who elicited comparisons to Vladimir Nabokov and James Salter. Sadly, he died just weeks before the release of his final fiction and will never know how it was received. The Last Judgment is a dark vision, an apocalyptic fever dream, a panorama of chiaroscuro lit by the torched South at the end of the Civil War. In this, his final novel, Steiner recounts the aftermath of Lincoln’s assassination and the defeat of the South in a style that is Proustian in detail, Jamesian in stateliness, and Faulknerian in its rhythms. It is a remarkable achievement. If you’re not put off by sentences that sometimes go on for an entire page — with enviable fluidity — and the unrelenting bleakness Cormac McCarthy fans seem to thrive on, give it a go.

Tess Lewis

2023 brought another bumper crop of excellent translations, but review coverage of them (Arts Fuse excepted) has lagged woefully behind. Three standouts that have not received the attention they deserve are:

Exiled Shadow by Norman Manea (translated by Carla Baricz) is an extended meditation on the experience of exile and an exquisite game of mirrors that reflects the narrator’s present and past lives as well as his literary soulmates. The unnamed narrator is, like Manea, a Romanian writer forced into exile in the 1980s, who lands first in Berlin then at a liberal arts college in upstate New York. Subtitled a “novel in collage,” Exiled Shadow interweaves passages and themes from the works of Adalbert von Chamisso, Robert Musil, Junichiro Tanizaki, Paul Celan, Eugenio Montale, Thomas Mann, and others, including Manea’s own books, creating a paean to a life of the mind lived with bodily immediacy.

Out of the Sugar Factory by Dorothee Elmiger (translated by Megan Ewing) could also be called a novel in collage. The narrator, like the author, a Swiss writer named Dorothee Elmiger, dives down one rabbit hole to research the history of the sugar industry and its present-day ramifications but soon finds herself trapped in a vast warren with branching and intersecting tunnels to slavery, addiction, desire, hunger, appetite, love, madness, Karl Marx, lotteries, and the film director Chantal Akerman, to name a few. What at first seems a chaotic, purely associative mosaic of images gradually becomes an intricately connected kaleidoscopic pattern that highlights the insolubility of the mind/body problem.

Book of Eve by Carmen Boullosa (translated by Samantha Schnee) is the Mexican author’s effervescent and irreverent retelling of the Book of Genesis from Eve’s point of view. Guided by her “fiery disobedience” and her unabashed delight in pleasure, Boullosa’s Eve offers a fierce corrective to the doctrinaire use of stories.

Drew Hart (*your ‘faithful correspondent’ in Santa Barbara, California)

In this neck of the woods, 2023 feels like a year in books you would call “sturdy.” That’s not to dismiss it, certainly not to malign it in any way — there were all kinds of contributions from established voices, along with newer ones. However, your F.C. *, while having liked a number of outings he went on with this year’s crop, is choosing to call your attention to two most exceptional pieces of work — these made the best impressions for originality, for stylistic excellence:

In this neck of the woods, 2023 feels like a year in books you would call “sturdy.” That’s not to dismiss it, certainly not to malign it in any way — there were all kinds of contributions from established voices, along with newer ones. However, your F.C. *, while having liked a number of outings he went on with this year’s crop, is choosing to call your attention to two most exceptional pieces of work — these made the best impressions for originality, for stylistic excellence:

Henry Hoke’s novel Open Throat (Farrar, Straus and Giroux) takes the cake as an act of the imagination — today’s world as perceived and narrated by a mountain lion living in the Hollywood Hills. At once, it succeeds as a dark fairy tale (some of it taking place at Disneyland!) and as an environmental telegram from the animal kingdom. Short enough to be read in one sitting, totally immersive, and too good to miss.

An entirely different proposition is at hand with the (largely overlooked) latest work by the venerated Mary Gaitskill, The Devil’s Treasure (McNally Editions). It’s a sort of omnibus — a selection of entries from her numerous fictions and essays, intertwined with autobiographical musings that tie her oeuvre together. We get a seldom-seen look into an observant and talented mind, a voyage through a writer’s life; it’s a great introduction to her career.

On with the show! Up ahead are efforts that have come to fruition after the specter of Covid, and hopefully the passing of that shadow will bode well for 2024…

Bill Marx

This gives me the chance to highlight some of my favorite reads that critics have overlooked over the past year — and to add some newbies.

Surviving Our Catastrophes: Resilience and Renewal from Hiroshima to the Covid-19 Pandemic by Robert Jay Lifton (New Press) — A recent New Yorker profile of the 97-year-old psychiatrist and prolific author has, hopefully, brought some well-deserved attention to this brilliant analyst of the encompassing psychological disturbances of war. For him, there’s no embrace of Eros without an acknowledgment of Thanatos. The bombing of Hiroshima was symptomatic of what Lifton calls a “genocidal mentality” that is also reflected in the Holocaust, Vietnam, the Climate Crisis, and our problematic response to the Covid-19 pandemic. As we mull over the 20th century and grapple with the 21st, it is difficult to argue with Lifton’s point in his inspiring new book that “we live in a landscape of holocaust.…On that basis (and without in anyway equating ordinary life to the experience of holocaust), we all have in us something of the witness of the survivor.” And that link may be a key to our survival.

Surviving Our Catastrophes: Resilience and Renewal from Hiroshima to the Covid-19 Pandemic by Robert Jay Lifton (New Press) — A recent New Yorker profile of the 97-year-old psychiatrist and prolific author has, hopefully, brought some well-deserved attention to this brilliant analyst of the encompassing psychological disturbances of war. For him, there’s no embrace of Eros without an acknowledgment of Thanatos. The bombing of Hiroshima was symptomatic of what Lifton calls a “genocidal mentality” that is also reflected in the Holocaust, Vietnam, the Climate Crisis, and our problematic response to the Covid-19 pandemic. As we mull over the 20th century and grapple with the 21st, it is difficult to argue with Lifton’s point in his inspiring new book that “we live in a landscape of holocaust.…On that basis (and without in anyway equating ordinary life to the experience of holocaust), we all have in us something of the witness of the survivor.” And that link may be a key to our survival.

Free to Obey: How the Nazis Invented Modern Management (Europa Compass) — Translated from the French by Steven Rendall, historian Johann Chapoutot’s short volume supplies a refreshingly tart, if at times dense, rebuke to our corporate media’s self-protective strategy regarding where they project fascist threats are to be found. The usual (and easy) targets are torch-wielding neo-Nazi groups and their ideological enablers. But the influence of the Third Reich can be found in far more respectable realms. It turns out that, after the war, Hitler’s regime served as an inspiration for capitalistic businesses around the world. White collar concerns eagerly embraced management strategies that had been concocted to keep the populace compliant in Nazi Germany. One surprising fascist perk: for the Third Reich, “productive power was sustained by joy, a joy produced by pleasure and leisure.” Who would have guessed it?

Roosters Crow, Dogs Cry (Open Letter) — In 2000, writer Pico Iyer visited Cambodia. It struck him as a “bleeding, often broken country where every moral certainty was exiled long ago, and a visitor finds himself in a labyrinth of sorts, every path leading to a cul-de-sac.” Still, Iyer believed that the trials of major Khmer Rouge leaders at the time represented an opportunity for closure: “It was a time of hope for ill-starred Cambodia.” Polish journalist Wojciech Tochman visited Cambodia over the past decade as part of his series on societies affected by genocide. (An excellent earlier volume, Like Eating a Stone: Surviving the Past in Bosnia, was published in translation in 2008.) Spare and agonizing, this gritty work of journalism examines — with perceptive sympathy — the lives of those who are living in the country’s lower depths. It turns out that Iyer’s cul-de-sac has morphed into a black hole, at least for the country’s underclass. (The wealthy continue to do just dandy because of foreign investment, especially from China.)

An Education in Judgment: Hannah Arendt and the Humanities by D.N. Rodowick. (University of Chicago Press) — OK, this is a volume tailored for the academic crowd, but it is clearly written (not much jargon) and proffers a lucid argument for the importance of arts criticism, the best I have encountered since Stephanie Ross’s Two Thumbs Up. The latter’s philosophical lodestar was Hume. Rodowick draws on Hannah Arendt (by way of Kant) to make a convincing case for the social potency of cultural judgment. As Rodowick puts it: “I aim to show that an education in judgement, whether in aesthetic, cultural, or other domains, is also a political force that is as local as the classroom where the skills practiced through conversations and disagreements about art, philosophy, and other areas of humanistic concern can be applied to many other domains of decision and action.” In other words, criticism of the arts, politics, and the preservation of cultural memory share a common element — they are acts of judgment, essential forms of public discussion that strengthen our sense of community.

Father and Son: A Memoir by Jonathan Raban (Knopf) — This will be the final book from the skillfully chameleonic Raban, who died in January, 2023 at the age of 80. He was born in England, but since 1990 resided in Seattle, Washington. Raban is best known for works of nonfiction that draw on the techniques of fiction to seamlessly merge disparate genres: travel writing, literary criticism, autobiography, and political commentary. The nonfiction standouts for me are Bad Land, Hunting Mister Heartbreak, Coasting, and Arabia.

Father and Son: A Memoir by Jonathan Raban (Knopf) — This will be the final book from the skillfully chameleonic Raban, who died in January, 2023 at the age of 80. He was born in England, but since 1990 resided in Seattle, Washington. Raban is best known for works of nonfiction that draw on the techniques of fiction to seamlessly merge disparate genres: travel writing, literary criticism, autobiography, and political commentary. The nonfiction standouts for me are Bad Land, Hunting Mister Heartbreak, Coasting, and Arabia.

The Raban volume I have the most personal affection for is 1989’s For Love & Money, an invigorating mix of arts critique, personal confession, and travel writing that remains one of the best books about the trials and tribulations of the writing life I have come across. The reviews in the collection are crackerjack, especially pieces on the British writers V.S. Pritchett, Evelyn Waugh, and the Victorian chronicler of the poor, Henry Mayhew. His gushy enthusiasm for the untrammeled self of American writers such as Saul Bellow and Eudora Welty breaks his wise rule that “the reviewer is there to write, not to melt away from the book in tongue-tied wonder,” but the author’s tangy exploration of the limits of English realism more than makes up for his crush on the New World. His customary persona was refreshingly prickly.

Raban’s talent as a critic is matched by his daunting powers as a memoirist. Sections about writing television plays, working for the late Ian Hamilton’s New Review magazine, and buying a boat in anticipation of a sea voyage are as crisp, compact, and imaginative as accomplished short stories. A thoughtful essay on English literature’s failure to write charitably and perceptively about characters who choose to live outside of the conventional family subtly draws on Raban’s presentation of himself as a somewhat ornery outsider. Throughout For Love & Money, Raban argues that the line between fiction and nonfiction should be invisible — this is a theme that runs throughout his books, which explore the fertile creative relationship between memory and the imagination.

And that brings us to Father and Son, which was published posthumously. In 2011, Raban suffered a debilitating hemorrhagic stroke that paralyzed the right side of his body — it left him in a wheelchair. It seemed (to those around him) to be the end of his career as a writer, but the resilient Raban made a slow and agonizing recovery back to crafting first-rate prose. The journey is beautifully chronicled in this book — 12 years in the making, written with the aid of voice dictation software. Raban details his struggles (some of them compounded by his thorny temperament) with stoic perceptiveness, enlivened, though never sentimentally, by his deepening relationship with his daughter, Julia. The author’s story is interwoven with chapters that deal with his father’s experiences in WWII, from Dunkirk and North Africa to Italy and the Middle East. Peter Raban is evoked through a powerful fusion of research, remembrance, fantasy, and his father’s love letters to his mother. This is an apt capstone to Raban’s career, a book that might well leave the reader melting away “in tongue-tied wonder.”

Preston Gralla

Any year in which so many of our greatest novelists, including Ann Patchett, Zadie Smith, Richard Russo, Richard Ford, Alice McDermott, James McBride, and Colson Whitehead, release books is a great one for literature. To anyone who prizes novels, it was a cornucopia.

That doesn’t mean that the biggest names released the best books, though. Some, as I note after my top picks, weren’t quite up to snuff. What did I find great? Here are my 10 favorite books of the year.

The Bee Sting by Paul Murray. The 650 pages of this novel will be among the fastest, funniest, and most deeply felt you’ll read. Like his previous novel, the Booker Prize-longlisted Skippy Dies, it mixes sharp wit and tragedy. This one’s even funnier and more moving.

Be Mine by Richard Ford. This is Ford’s fifth Frank Bascombe book. It’s not quite on par with the four others, but any time I get to spend time with Bascombe is time well spent. You’ll probably feel the same.

Somebody’s Fool by Richard Russo. Russo’s Nobody’s Fool and its follow-up Everybody’s Fool featured one of contemporary American literature’s great characters, the irresponsible, bad luck-bedeviled, bighearted, impossible-to-bear blue-collar loser Sully. To my chagrin and the chagrin of countless others, Russo killed off Sully in Everybody’s Fool. In this book, his estranged son Peter proves to be a chip off the old blockhead. Sully fans will rejoice.

The Postcard by Anne Berest. In this superb piece of auto-fiction, an unsigned postcard of Paris’s Opéra Garnier in Paris is sent to the Berest household, with no message on it other than the hand-printed names of Anne’s maternal great-grandparents, Ephraïm and Emma, and their children, Noémie and Jacques, who were all killed at Auschwitz. That sets in motion an investigation into Anne’s family’s past, a probe that looks into things she has consciously avoided knowing as well as things her mother has tried to forget. The narrative does more than delve into who sent the postcard and why; it goes beyond excavating the family’s history and revealing how its members were killed. The Postcard explores the depth of France’s and its citizens’ unacknowledged antisemitism and war crimes. It’s the best book I’ve read in years. I’ll never forget it.

The Heaven and Earth Grocery Store by James McBride. The New York Times describes this as a mystery book locked inside a Great American novel, and with good reason. It starts with the discovery of a skeleton in a well, which begins an epic journey into the past and the heyday of the Pottstown, Pennsylvania, neighborhood of Chicken Hill, with its close ties between the Blacks and Jews who lived there.

Küntslers in Paradise by Cathleen Schine. The adrift 24-year-old Julian Künstler moves into his 93-year-old grandmother Mamie Künstler’s guesthouse in Venice, California, during the pandemic. His girlfriend has dumped him and his roommate has moved out. Lost and directionless, he expects little from relocation other than an easy place to crash. But this is a book by Cathleen Schine, an author who excels at warmth and wit — you know that situation will change. We meet the Künstlers, a family who fled Vienna in 1929 to escape the Nazis and landed in the émigré ferment of Los Angeles in the 1930s. The clan moved among rarified company back then, befriending the likes of Arnold Schoenberg, Christopher Isherwood, Thomas Mann, and Greta Garbo. You’ll love spending time in their company. You’ll love reliving their past. You’ll love Mamie and Julian, who form an unlikely bond. And you’ll love this book.

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton. Eco-anarchists, a Musk-like billionaire, and 432 pages of plot. That may sound trite, but it’s not. It’s a page turner that has much to say about the disaster of climate change. It dramatizes the mixture of self-importance and idealism found in many activists, and the egotism and outright evil of the super-wealthy like Musk and his ilk.

Absolution by Alice McDermott. The early days of the US involvement in the Vietnam War, in 1963 Saigon, is not the place you’d expect one of our greatest short story writers and novelists to set a book. She’s generally concerned more with Irish-Americans in the States. This novel centers on an Irish-American couple from New York, Patricia Kelly and her Navy intelligence officer husband, Peter. Patricia’s frustrating travails, as she attempts to master the role of perfect military wife in a time and place that is changing faster than anywhere in the world, set the stage for the protagonist’s metamorphosis, and America’s as well.

Brooklyn Crime Novel by Jonathan Lethem. I was born in Brooklyn, though I moved as a young child to the suburbs. Still, I spent a chunk of my youth in the city, with cousins, aunts, uncles, grandparents, and a motley tribe of more-distant relatives. For me, my memories have been the true Brooklyn, the ethnic Brooklyn, not the playground it’s become for flannel-shirt-wearing, craft pickle store owners with carefully curated facial hair. So Lethem’s books have always been catnip for me, none more than this one, which portrays half a century of Brooklyn’s gentrification. It mixes gentle satire with deep nostalgia: the narrative viscerally portrays how the borough has been transformed by economic and social change — and not in a good way.

Hope by Andrew Ridker. Take a Harvard-educated doctor who’s caught falsifying data for a medical trial and mix in his activist wife who leaves him for a woman, his children, who can’t quite get their lives together, and his mother, who’s scammed by a Turkish teenager she’s met on OKCupid. Add a sharp seasoning of mischievous satire: Pussy Katz is a Jewish porn star. The result is a savory meal of a story you’ll be tempted to wolf down as fast as possible. My recommendation: Slow down and enjoy each morsel.

My three biggest disappointments are all good novels. But when it comes to literature, I grade on a curve, and none of them match their author’s best work.

Zadie Smith’s historical novel The Fraud was well done and focused in large part on the lives of characters who are typically omitted from conventional narratives. But, for me, the story didn’t move far enough away from the conventional: the book lacked the vitality and sheer brilliance of her best work, White Teeth, Swing Time, and On Beauty.

I found Ann Patchett’s Tom Lake similarly disappointing. Everything Patchett writes is superbly written, but I found this one nostalgia-soaked and inert compared to much of her previous work.

Colson Whitehead’s Crook Manifesto, a follow-up to his 2021 Harlem Shuffle,was a very good, very quick read. But it was a far cry from his two Pulitzer-Prize winning novels The Nickel Boys and The Underground Railroad.

Peg Aloi

Yes, we all want to read more and dammit, I’m trying. Here are some of my favorite books from 2023.

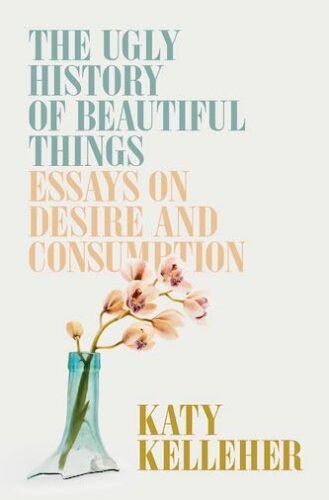

The Ugly History of Beautiful Things: Essays on Desire and Consumption by Katy Kelleher (Simon & Schuster) Kelleher’s writings on color and art for The Awl and the Paris Review are well worth seeking out. Her fascination with the colors, textures, and natural and man-made histories of objects is given glorious free rein in this fascinating, informative, and beautifully written collection of essays. From mirrors and gemstones to paints and perfumes (and much more), Kelleher delves into the cultural, scientific, literary, and personal (her distinctively sensitive perspective is part of what makes this book delightful) stories behind the objects that most of us take for granted.

The Black Guy Dies First: Black Horror Cinema from Fodder to Oscar by Robin R. Means Coleman, PhD, and Mark H/ Harris (Saga Press). It’s been a long wait for a comprehensive deep dive into Black horror cinema, and this fantastic book fills that absence with brilliant insights, deep history, and great writing. Any book dedicated to Duane Jones, Scatman Crothers, Mantan Moreland, and Pam Grier — and that locates its origin story in 1968 — is obviously treating this subject right. An indispensable book for horror aficionados, and a jaw-dropping, thrilling exploration of the history of Black horror tropes, themes, and touchstones.

Elixir: A Parisian Perfume House and the Quest for the Elixir of Life by Theresa Levitt (Harvard University Press). Part scholarly history and part occult thriller, this story of two perfumers who fancied themselves alchemists is riveting and beautifully written. In the 1830s, Édouard Laugier and Auguste Laurent worked for the oldest perfume house in Paris, and spent their free time trying to unlock the secret of eternal life. Amazingly, their controversial experiments led to actual scientific breakthroughs in both chemistry and biology.

Art of the Grimoire: An Illustrated History of Magic Books and Spells by Owen Davies (Yale University Press) This richly illustrated book by one of the foremost contemporary scholars of the history of witchcraft and the occult is an enchanting read. It is also meticulously researched and effectively explores the cultural and historical significance of magical texts as they intersect with religion, literature, science, colonialism, art, and culture.

Night Side of the River: Ghost Stories by Jeanette Winterson (Grove Press) Despite her reputation for dark themes, award-winning writer Winterson has never been associated with horror — until now. These stories are deftly written, chilling, and thoroughly contemporary in their evocation of ghosts and paranormal phenomena. Yet they are also steeped in a Gothic sense of unease and melancholy. Perfect reading for gray rainy days or stormy nights.

Tagged: Allen Michie, Bill-Marx, Drew Hart, Ed Meek, Matt Hanson, Peg Aloi, Preston Gralla, Roberta Silman, Tess Lewis

This cluster of reviews is like a menu at a good restaurant. Having some inclination but not the time to read all of these books, the reviews will help me choose. For which, thanks.