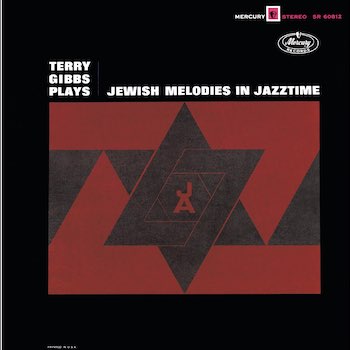

Musician Interview: “Terry Gibbs Plays Jewish Melodies In Jazztime” turns 60

By Noah Schaffer

The album’s explicit mix of modern jazz and klezmer set a template that is still being used by many of today’s most prominent Jewish music experimentalists.

The end of 2023 concludes the celebrations of several milestone music anniversaries. The 50th anniversary of hip-hop got a lot of attention, and the centennials of Hank Williams, Sam Rivers, and Wes Montgomery were also observed.

It also marked the 60th anniversary of an infrequently discussed record that had an oversized place in music history: Terry Gibbs Plays Jewish Melodies In Jazztime. The album matched bebop vibraphonist Gibbs and some of his fellow jazz musicians with a rollicking klezmer band.

Gibbs was far from the first Jewish jazz musician to explore his roots – Benny Goodman had recorded the Yiddish melody “Bei Mir” in the ’30s. But the album’s explicit mix of modern jazz and klezmer set a template that is still being used by many of today’s most prominent Jewish music experimentalists.

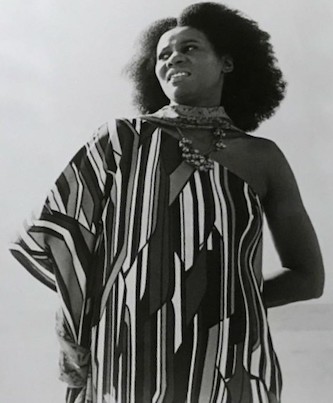

Also notable on the Quincy Jones-produced session was the presence of a pianist making her credited recording debut: Alice Hagood, who would later be known as Alice Coltrane. The future wife of John Coltrane remains an enormously influential figure whose injection of spirituality into jazz resonates today in the music of many of today’s top improvisers. She would also appear on Gibbs’ Hootenanny My Way, which foreshadowed the now common practice of jazz musicians playing folk and country melodies.

While Gibbs is retired from playing, he remains very active at 99. Earlier this year New Bedford’s Whaling Sounds Records released The Terry Gibbs Songbook, a new collection from the Terry Gibbs Legacy Band, a unit overseen by Gibbs that includes his son Gerry on drums. The vibraphonist recently spoke with The Arts Fuse via telephone from his Los Angeles home about the anniversary of Jewish Melodies in Jazztime.

Note: if there’s any questions you’d like to ask, you can do so any Saturday when Gibbs hosts his weekly Facebook live Q&A sessions.

ArtsFuse: How did Jewish Melodies in Jazztime come about?

Terry Gibbs: You know how they had done these Latin jazz records where they were playing jazz with a conga drummer that gave it that Latin feel? I kept that idea. My whole family escaped from Russia; they came here about 1922. Both my father and my brother were musicians, and they brought all this Hasidic music that you can’t find in any book. It’s like a jazz musician who learns at a jam session — you don’t learn anything on paper, it’s in your head. So I went to Quincy Jones, who was the head of Mercury Records, which I had a good contract with. I said I’ve got an idea for doing this.

AF: Can you talk about how you ended up using both jazz players and artists who were active on the New York Jewish music circuit? How did these players from different backgrounds gel together?

Gibbs: That was my brother’s [drummer Sol Gage] band! Quincy liked the idea, so just two days later I got the musicians. I wrote the music out, but they didn’t need any music, they just showed up and played. All the musicians already knew songs like “Papirossen” and “Nyah Shere,” and I just wrote out the chord changes for Alice and the bass player. And then I wrote two of the songs myself, “S&S” and “”Shaine une Zees (Pretty & Sweet).” So on the record my brother and his band play the front part, then we play the middle, and they play the ending part.

Alice Coltrane in 1972. Photo: wiki common

AF: How did Alice Coltrane appear?

TG: She was Alice McLeod [her maiden name – the records credits reflect her very brief marriage to singer Kenny Hagood]. I go into detail about this in my autobiography. We had just played at Birdland. She was in my band and she fell in love with John and John’s playing. In Jewish music there are these Middle Eastern runs – “dye dye dye dye dye dye dye.” And in John’s playing there were a lot of these. Alice got a lot of those from John. I always say that I was the Jew, but Alice just ran away with the album, the way she played. She played all those runs. She just fell into it like she was Jewish! She wiped me out!

AF: How did you meet her?

Gibbs: I had moved from New York to California in 1957, and I had a band with a pianist named Terry Pollard. She was from Detroit. When I called the bass player, he said ‘There’s another girl piano player who is also from Detroit who I think you’ll love.’ I was a bebop player. Not everyone had the articulation and bebop feel. So I came to New York and was introduced to Alice and she was great. I hired her and she was in my band for an entire year. I taught her how to play vibes and we would do a showbiz thing where we’d play together.

I introduced her to John, they fell in love. I had a very big gig coming up at a restaurant in Chicago called the London House that hired people like Oscar Peterson and Nat King Cole and George Shearing. A week before the show she called me and said ‘Terry, John wants to marry me and go to Sweden.’ She was a sweetheart. With anybody else I would have called my attorney! But I didn’t feel that way, she was so great. I ended up hiring Walter Bishop Jr., who was also a great piano player.

AF: What were the sessions like?

Gibbs: When Quincy Jones showed up for the date he was wearing a yarmulke and a tallit! And in the middle of the date my friend brought me a box of matzah. The Jewish musicians were great players and their sound was authentic. My brother was the Art Blakey of the Jewish drummers. He could swing from here to Yugoslavia! Because Jewish music can really swing.

AF: Clarinetist Ray Musiker is still alive. [Musiker spoke about making Jewish Melodies in Jazz Time in this 2020 podcast.]

Gibbs: Musiker was great, and his brother Sam and father-in-law [Dave Tarras] were also great. Sammy used to play with Gene Krupa’s band, because in those days everybody had to have a clarinet player because of the renown of Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw. [The music on a 1955 record by the Musiker Brothers and Tarras was recently performed live in New York.] And Ray’s son, Lee Musiker, played with Buddy Rich’s band and then started conducting Broadway shows.

Vibist Terry Gibbs at the age of 92. Photo: Jewish Journal

AF: Had you played this music with your family?

Gibbs: Oh yes, my father [Abe Gubenko] was a successful Jewish bandleader. The way it worked is that if you were having a wedding or bar mitzvah it would be at a catering hall. So in those days the bandleader would make friends with the catering hall owner. My father was the house band leader in two of those halls. So when someone was getting married the catering hall owner would recommend my father, almost like a booking agent. And maybe on a Saturday he would have two weddings, so he knew which musicians to hire. Nobody showed them the music, they just came there and played.

Do you know the name of Naftule Brandwein? He played with my father and I got to play with him. He was an alcoholic. Now I don’t customarily use any cuss words when I’m talking, but I come from Brooklyn, and if I quote someone I say what they say. So I was about 16 years old and also played drums and Brandwein asked my father to use me on a job. He was a little out there as a person. He did drink on his own jobs, and when you’re 16 you’ve got plenty of energy and have the habit of rushing the little music a little bit. So he turns around and says to me “Gubenko, you fuck, you’re rushing!” Nobody played the clarinet like him. He would have a suit with all these lights, and all the other lights would go off so you’d just see his lights. One time we were playing and he tripped and the lights made a spark, and he yelled “I’m on fire!” and he jumped into the pool!

AF: How was the record received? Would you call it a success?

Gibbs: Oh yes, the album was so much fun, and you know what, it’s still selling in Japan. It was different, and I was fairly hot then. Playing jazz on the Jewish songs, that was my cup of tea. It was probably rooted in my heritage, because I grew up playing those songs with my father. So I knew that music really well, and the musicians themselves were so great.

Noah Schaffer is a Boston-based journalist and the co-author of gospel singer Spencer Taylor Jr.’s autobiography A General Becomes a Legend. He also is a correspondent for the Boston Globe and DigBoston, and spent two decades as a reporter and editor at Massachusetts Lawyers Weekly and Worcester Magazine. He has produced a trio of documentaries for public radio’s Afropop Worldwide, and was the researcher and liner notes writer for Take Us Home – Boston Roots Reggae from 1979 to 1988. He is a 2022 Boston Music Award nominee in the music journalism category. In 2022 he co-produced and wrote the liner notes for The Skippy White Story: Boston Soul 1961-1967, which was named one of the top boxed sets of the year by the New York Times.