Opera Album Review: Finally, “L’Egisto” — Complete and Amazingly Reimagined

By Ralph P. Locke

Tenor Zachary Wilder — a Boston favorite — and others shine in a Cavalli opera from 380 years ago.

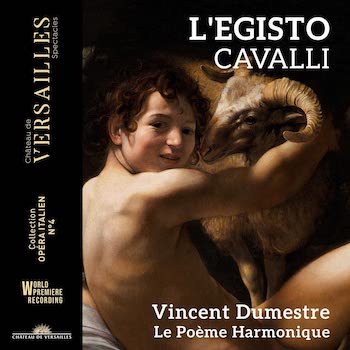

CAVALLI: L’Egisto

Ambroisine Bré (Climene), Sophie Junker (Clori), Marc Mauillon (Egisto), Zachary Wilder (Lidio), Romain Bockler (Hipparco).

Le Poème Harmonique, cond. Vincent Dumestre.

Chateau de Versailles Spectacles 76 [2 CDs] 126 minutes

Throughout the mid and late 17th century, Cavalli’s operas were a major cultural activity and tourist attraction in Venice — an international center of trade –and other Italian cities. But none was published. We are fortunate that most of the manuscript scores did survive, primarily in Venice’s Biblioteca Marciana.

A small army of performers and musicologists have been gradually piecing each of these operas together and making editions to enable study and performance. One notable earlyish result was René Jacob’s brilliant 1988 Harmonia Mundi France recording of Giasone (or Il Giasone, to follow the Italian practice of the era; a video version is online). I heartily praised here a 2006 recording of Ipermestra belatedly released a few years ago, led by Mike Fentross.

L’Egisto (Venice, 1643) was the second of nearly a dozen operas that Cavalli wrote in collaboration with librettist Giovanni Faustini. Later ones would include L’Ormindo and La Calisto, both of which found new life in the 1960s-’70s, thanks to versions heavily reorchestrated by Raymond Leppard for use in modern opera houses and with big-voiced singers.

There were two previous recordings of L’Egisto, each on two LPs and with the score probably cut by at least a third: a version from Munich featuring Trudeliese Schmidt and one conducted by Renato Fasano with Luigi Alva and Sesto Bruscantini.

In the new recording, fortunately, the score is given more or less complete, and we are in the capable hands of an elegantly HIP conductor and ensemble. (HIP is one familiar way to say Historically Informed Performance. Sometimes people refer to it as PPP, i.e., Period Performance Practice.) The ensemble bears the name Le Poème Harmonique and consists of 17 players, including those in the continuo. This is smaller than the orchestra and continuo for some Baroque opera recordings I have reviewed here, especially of French works. But, in the imaginative hands of Vincent Dumestre and his dozen-and-a-half pluckers, blowers, and bow-ers, the many recitative exchanges come to life, and the 35(!) arias, mostly short, bring frequent and contrasting pleasures, not least several laments for Climene and one for the title character (near the beginning of Act 2). Particularly famous at the time were the passages in which Egisto goes mad for a time (Act 3, scenes 5 and 9).

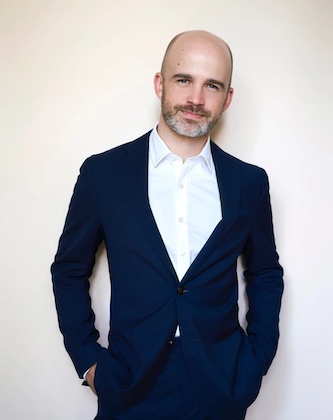

Tenor Zachary Wilder. Photo: Pauline Darley

The opera, after a brief and particularly lovely prologue for Night and Dawn, mixes more than a dozen characters, most notably two shepherd-and-nymph couples: Egisto and Climene, and Lidio and Clori. The bonds of their respective love for each other are tested repeatedly, not least by repeated interventions from gods, heroines, and emblematic figures (likewise from Greek mythology), such as Apollo, Venus, Semele, Phaedra (here Fedra), Dido, Beauty, Sensuality, and Amore (i.e., Cupid: Venus’s son, proud of his power), plus a Fury from the Marsh of Acheron (a river believed to connect to Hades). And there’s an outsider to the two couples: Hipparco, who has his own longings that threaten to further disturb and rearrange the couplings.

The opera comes from a period before Italian opera bifurcated into serious and comic strands and before castrati and highly florid singing came to dominate the “seria” type. On this recording, we hear relatively natural declamation throughout (that is, little coloratura), and no countertenors, nor women in male roles. I wish the booklet-essays had explained what voice-types probably took each role in 1643. Cavalli authority Jennifer Williams Brown tells me that Lidio’s and Dema’s parts were notated in alto clef, that is, for castrato; perhaps some of those characters’ passages have been transposed downward for the performers.

The five singers that I list in the header have more to do than the others, and do it marvelously. I have praised the two main tenors previously: the incisive-toned Marc Mauillon (in works by Matthew Locke and by Offenbach) and the sweeter Zachary Wilder. Wilder, an American, has become a major star on the early-music circuit. His recent joint concert (with the equally marvelous Swiss-born tenor Emiliano Gonzalez Toro) in New England Conservatory’s Jordan Hall, presented by the Boston Early Music Festival, was videorecorded and can be watched through December 16. (I termed his singing appropriately “divine” in the role of the god Apollo in Lully’s Psyché.) But even the singers who take briefer roles are marvelously suited for their tasks, such as the tenor Nicholas Scott, who offers a brilliant cameo performance, done without caricature, as the opinionated nursemaid Dema at the beginning of the second CD.

I was pleased to reencounter, in two roles, Caroline Meng, who had shown great dramatic and musical command as the schoolmistress in the wonderful recording of Messager’s superb 1897 opéra-comique Les p’tites Michu (about which I have written an extensive review-article).

In short, there is not a moment when the interest lags in this amazing reimagining of an opera from 1643. I gather that the Venetian opera houses in that era used only string instruments, not winds, but I was happy for Dumestre’s departure from strict authenticity in this regard. There are surely so many other aspects of these works that we cannot recover. Varying the instruments helps increase the appeal to the ear.

The sound quality is clear and balanced. The booklet essays are informative if too short (they are given in English, French, and German). And the libretto is given in the original, and in French and English translations. The English, credited to a translation firm rather than an individual, contains numerous confusing errors.

The sound quality is clear and balanced. The booklet essays are informative if too short (they are given in English, French, and German). And the libretto is given in the original, and in French and English translations. The English, credited to a translation firm rather than an individual, contains numerous confusing errors.

Several different numbering systems are juggled in the booklet: act numbers, scene numbers, CD numbers, and track numbers (beginning again, in the tracklist, with 1 at the beginning of an act, but through-numbered in the libretto itself). I kept getting lost.

Also, it would have helped if the tracklist had included page numbers for each scene and track. And if the various “sinfonie” (instrumental tracks) had been mentioned in the libretto; instead, the text simply skips from, say, track 26 (called CD 2 track 2 in the track list) to track 28. Egisto’s lament is called one thing in the booklet-essay, but something else (the line of recitative that precedes it) in the tracklist. Some consistency, please!

By the way, there is a whole backstory to the plot that the essays don’t mention. I strongly recommend that you read Ellen Rosand’s entry in OperaGrove, now part of www.oxfordmusiconline.com.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Ambroisine Bré, Cavalli, Chateau de Versailles Spectacles, L'Egisto, Le Poème Harmonique, Marc Mauillon, Romain Bockler, Sophie Junker