Jazz Album Reviews: Cal Tjader’s Quintet and Wes Montgomery with the Wynton Kelly Trio in the Mid-’60s

By Steve Elman

Two upcoming releases of restored radio broadcasts offer so much good listening and so much deeply satisfying jazz that they deserve to share the spotlight. One of them is destined to be seen as a landmark document in jazz history.

Radio has a short memory. Even dinosaur radio stations like Boston’s WBZ-AM rarely mention the fact that they’ve been broadcasting for more than 100 years. These pioneer stations, and many that came after the first wave of commercial radio, witnessed every cultural phenomenon in the 20th century that had an audio component. Nearly all of their broadcasts — some historic, and some significant only in retrospect — have been lost forever.

Radio has a short memory. Even dinosaur radio stations like Boston’s WBZ-AM rarely mention the fact that they’ve been broadcasting for more than 100 years. These pioneer stations, and many that came after the first wave of commercial radio, witnessed every cultural phenomenon in the 20th century that had an audio component. Nearly all of their broadcasts — some historic, and some significant only in retrospect — have been lost forever.

Why? Ask the press reps of most stations about their tape (or transcription) archive, and you’ll usually get the response, “What archive?” Every time a program director looks at the wall of old tape (or now, the folders of old digital files) and says, “What the hell is this stuff?” history is about to go out with the trash.

If it wasn’t for the obsessives, people who recorded things off the air because they might be important someday, or concerned professionals who squirreled away stuff they valued in their attics or basements, the archive of jazz would be limited to what commercial labels chose to record and release.

Instead, there are hundreds of important, even precious, live dates that survive today because someone captured them and others gave them the loving care needed to improve their audio quality sufficiently (and sometimes pay the players appropriately) so that they could be made available to the general public.

On Black Friday 2023, the day after Thanksgiving, two collections of radio airchecks (including one priceless private recording made around the same time) will be issued, and both are treasures.

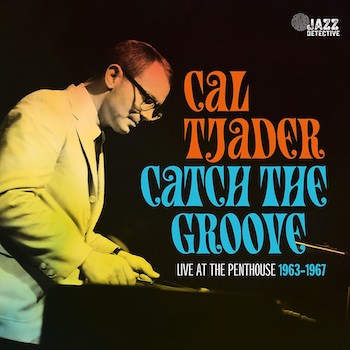

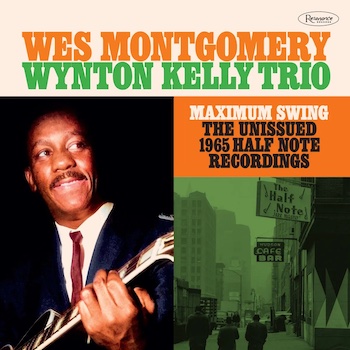

Vibraphonist Cal Tjader’s Catch the Groove: Live at the Penthouse 1963-1967 (Jazz Detective) is a much-needed documentation of Tjader’s delightful small combos of the era. Perhaps it is not as important as Maximum Swing: The Unissued 1965 Half Note Recordings (Resonance) by guitarist Wes Montgomery and the Wynton Kelly Trio. But the two releases offer so much good listening, so much deeply satisfying jazz, that they deserve to share the spotlight.

Some of these recordings have been made available before as bootlegs, but none of the tracks ever sounded as good as they do here. I’ll have a tip of the cap to the production and engineering teams in the “More” section below.

In addition, the two collections share one curious biographical quirk: each adds immensely to a one-off Verve LP from the 1960s. Those two Verve releases were, up to now, the only legitimate recordings available of each of these groups.

I’ll save the better for later, and begin with Tjader.

I still own a vinyl copy of Cal Tjader’s Saturday Night / Sunday Night At The Blackhawk, San Francisco (Verve, 1962), the only commercial release that preserved Tjader’s working quartet of the time – pianist Lonnie Hewitt, bassist Freddy (aka “Fred”) Schreiber, and drummer John (aka “Johnny”) Rae, who sometimes traded off with Tjader to play vibes while the leader switched over to the drum kit. The feel of that club date was infectious — a dynamic leader who knew how to swing with intelligence, a smart selection of good tunes guaranteed to please an audience, a simpatico group of sidemen, and enthusiasm from a knowledgeable crowd. All these factors combined to put me at a ringside table with the other jazz sophisticates when I wasn’t even old enough to drink.

I still own a vinyl copy of Cal Tjader’s Saturday Night / Sunday Night At The Blackhawk, San Francisco (Verve, 1962), the only commercial release that preserved Tjader’s working quartet of the time – pianist Lonnie Hewitt, bassist Freddy (aka “Fred”) Schreiber, and drummer John (aka “Johnny”) Rae, who sometimes traded off with Tjader to play vibes while the leader switched over to the drum kit. The feel of that club date was infectious — a dynamic leader who knew how to swing with intelligence, a smart selection of good tunes guaranteed to please an audience, a simpatico group of sidemen, and enthusiasm from a knowledgeable crowd. All these factors combined to put me at a ringside table with the other jazz sophisticates when I wasn’t even old enough to drink.

Now I can hear the band again, in all its glory, thanks to some beautifully preserved airchecks of live performances broadcast by KING-FM at a club in Seattle. The new two-CD set on Jazz Detective proves that the 1962 LP wasn’t a fluke; this combo played at the same consistent level of excellence night after night. Six different club dates are represented here (from 1963, 1965, 1966, and 1967), and there isn’t a dead track among the 37 tunes. Even better: there is only one repeated tune among the 37 (there are two takes of “On Green Dolphin Street,” which has been so overplayed that we didn’t really need either one). This variety shows how versatile the band was, how readily they jelled in Cal’s little arrangements, and how they made each tune their own. The repertoire here doesn’t even duplicate any of the eight tunes on the old Verve LP. It may not be unusual for a jazz group to have a book of almost 50 tunes to draw on over a five-year span, but to play them all so well is remarkable.

It’s all the more remarkable that the bass player is not consistent from date to date. Four different bassists play with Tjader in these six sessions (seven counting the Verve date), and each of them sounds like he is part of a perfect little machine.

Essentially, there are two of Tjader’s working groups documented here, both of which had Latin percussionist Armando Peraza aboard, reflecting Cal’s increasing success with Latin-jazz hybrid material. The first quintet (1962-65) usually included Hewitt and Rae – although the first session in this new set has Clare Fischer at the piano, a player who had remarkable rapport with Tjader and appeared with him on several of his best-selling LPs, and Bill Fitch filling in for Peraza. The second quintet (1966-67) replaced pianist Hewitt with Al Zulaica and drummer Rae with Carl Burnett, and it sounds a bit smoother and more refined, thanks to Burnett’s sensitive drumming.

None of these players ever became world-famous, although Fischer and Burnett are known to most jazz fans. But each of the groups has amazing consistency, undoubtedly due to Tjader’s precise sense of what he wanted on stage.

Highlights? I’ll name three.

Hewitt’s tune “Pantano” had its first exposure in Cal’s best-selling LP Soul Sauce (Verve, 1964). The months of playing this tune before live audiences have obviously sharpened everyone’s teeth, and instead of a laid-back near-background performance like the one on the LP, we get something more substantive, in a brighter tempo. This is Hewitt’s feature, and he has fun in his solo quoting Benny Golson’s “Killer Joe.” The only thing I miss is a solo from Cal; he surely would have made the most of the blues inherent in it.

Paul Horn’s “Half and Half” is a delightful surprise. This tune probably found its way into the book from the days that multireedman Horn worked in Cal’s band. The first known commercial release, on Horn’s LP Something Blue (Hifijazz, 1960), hinted at a Latin feel, in sections that alternated with straight 4/4. Four years later, Cal turns it into real Latin jazz, a feature for conguero Peraza, with Rae up on his feet playing timbales. Too bad it fades, probably to avoid a talkover by host / engineer Jim Wilke.

Cal’s take on Bunny Berigan’s “I Can’t Get Started” is another gem. Even though he played with harder mallets than some other vibists, Tjader knows just how to state this classic ballad and elaborate on it, so that it has softness but keeps an edge. He eases beautifully into double-time, with perfect support from Monk Montgomery on bass and Carl Burnett on drums, and the heat gradually increases until the return of the ballad feel for the outchorus. This is a classic mid-1960s interpretation, and it hasn’t dated a bit.

But these are just some notable tunes in a collection that is elegantly played and impeccably performed, from first track to last. It’s a primer for any jazz band today seeking guidelines on how to construct a live set — play tunes with ear appeal, give everyone judicious feature spots, keep the performances economical, and pace the show so that enjoyment, excitement and depth are offered in equal measure.

But these are just some notable tunes in a collection that is elegantly played and impeccably performed, from first track to last. It’s a primer for any jazz band today seeking guidelines on how to construct a live set — play tunes with ear appeal, give everyone judicious feature spots, keep the performances economical, and pace the show so that enjoyment, excitement and depth are offered in equal measure.

You want more risk-taking and more fire? OK, pick up Maximum Swing.

There must have been a frothy sweat of anticipation among the world’s jazz guitarists when the release of this material was announced. The only commercial recording of Wes Montgomery with Wynton Kelly’s trio, from September 1965, was first issued on LP (Smokin’ at the Half Note, Verve, 1965). 40 years later, the original recordings from the period were finally rereleased on CD as they should have been all along, minus string section sweetening and including all the takes available (Smokin’ at the Half Note, Verve, 2005).

Those 1965 recordings became touchstones for guitarists who were young in the 1960s. Montgomery’s beautiful sound, his powerful swing, and his incredible inventiveness were all on ample display, and the inspiration of Miles Davis’s great early ’60s rhythm section (1959-63) — pianist Wynton Kelly, bassist Paul Chambers, and drummer Jimmy Cobb — proved the ideal foundation for the guitarist’s work.

That partnership lasted only a few months. Short-lived as it was, it became legendary among jazz fans, taking its place alongside the stellar combination of guitarist Grant Green with pianist Sonny Clark, and the clairvoyant interplay of guitarist Jim Hall and pianist Bill Evans.

So, does Maximum Swing, with two CDs of live material and 17 tracks that have only been available on dreadful bootlegs to date, deliver on its promise? Does it ever.

It’s important to note that the sound quality here does not compare with that of the Tjader set. The tapes of Tjader’s club dates at the Penthouse were archived by the club’s owners; presumably they were the original radio tapes or first-generation copies.

The Montgomery-Kelly material comes mostly from live broadcasts on WABC-FM hosted by Alan Grant, and it’s clear that the original source material is long gone. But these recordings, probably made off-air and rerecorded a number of times with a loss of quality in each duplication, have been raised from near-death by the devotion and care of producer Richard Seidel and engineer Matthew Lutthans. They have worked minor miracles to make these important documents sound as good as modern technology will permit. Once you adjust your ears to the fact that these tunes lack the high frequencies that give sound its sharpness and snap, you will be able to hear past the flaws and appreciate the genius of the players.

That first Verve LP documented live material from September 1965. The new set has only three tracks from that month. The rest of the material is from two months later, and it shows in every way how the group improved as it played together.

The capper is the set of recordings that close Maximum Swing, which were not radio broadcasts, but private recordings made in the Half Note in late 1965 by someone with a bit of technical expertise. Lutthans reports that this group of five tunes, with even lower fidelity than that of the radio airchecks, presented the most serious engineering challenges of all, but there is no doubt that the restoration was worth all the effort. These are the only known recordings of the group as it must have sounded when unfettered by the demands of radio broadcast or caveats from a record producer.

Unlike the Tjader recordings, which essentially document his group’s work with little framing from KING-FM (except the occasional fadeout, probably because of time constraints), the Montgomery-Kelly material was excerpted from hour-long live broadcasts on WABC-FM and includes some patter from Alan Grant. It appears that the first half-hour or so of each show was devoted to Kelly’s trio, with Montgomery joining them for the last half-hour as a special guest, but all we hear in this set are the tunes with Wes. Since he already had had ample opportunity to solo, Kelly almost always confines himself to comping and support behind the guitarist. So we get 12 tunes with Montgomery as the star and almost the only soloist — not that there’s anything wrong with that.

Unlike the Tjader recordings, which essentially document his group’s work with little framing from KING-FM (except the occasional fadeout, probably because of time constraints), the Montgomery-Kelly material was excerpted from hour-long live broadcasts on WABC-FM and includes some patter from Alan Grant. It appears that the first half-hour or so of each show was devoted to Kelly’s trio, with Montgomery joining them for the last half-hour as a special guest, but all we hear in this set are the tunes with Wes. Since he already had had ample opportunity to solo, Kelly almost always confines himself to comping and support behind the guitarist. So we get 12 tunes with Montgomery as the star and almost the only soloist — not that there’s anything wrong with that.

Nonetheless, those tracks are artificial renderings of how the group really sounded in performance, and there are some unfortunate fadeouts with talkovers by Grant at the end of each set. They especially mar two of the takes of “No Blues.”

The restrictions are gone in the nonbroadcast set. It is hair-raisingly superb, some of the best live jazz ever recorded.

What makes this music great?

Of course, the players are top-notch, and each is in his prime. Of course, Montgomery is a consummate guitar stylist, and here he stretches out in a way he rarely could in the studio. Of course, Kelly is one of the best supporting pianists who ever touched a keyboard. Of course, Jimmy Cobb is a master of taste, with an intuitive sense of how to shape the ambience of the ensemble with just the right amount of percussion. And remarkably, the four bass players here, each subbing for Paul Chambers (who was reportedly ill at the time), fit perfectly.

But the whole is greater than the sum of these individual talents, for a number of reasons.

Musicians talk about the indefinable boost they get from live performance. The adrenaline probably courses a bit more when they play in New York City, where audiences are quick to judgment and quick to passion. And the mid-1960s were a kind of golden era for small-group jazz, before the rock and roll wave became a flood, when the hip and the wanna-be-hip went to jazz clubs, especially top-line jazz clubs in New York like the Half Note, to hear the music that was the epitome of cool.

And there is the crowning factor of rapport. The comfort of being in the company of players who think like you allows an artist to give free rein to his or her inspirations in the moment, and those inspirations are what jazz people live for.

Pianist Wynton Kelly. Photo: Wiki Common

Just one technical example of the rapport that contributes so much to this music: Wes tends to play slightly behind the beat, which makes him sound relaxed even at fast tempos. Wynton understands this and matches that sense of relaxation with his comping. Jimmy Cobb understands it as well. And all three do this without any sense of force or falseness. As a result, the music has a powerful dynamic of tension and release without any haste or rush.

Wes does not put on a display of fabulous guitar-hero technique in these performances, nor does he need to. Rather, his playing here is what happens when a master knows exactly what he wants to do, and is able to do it without any constraints.

Beyond its overall importance, Maximum Swing has many specific delights. It gives us 10 tunes not included in the repertoire of the Verve release — including an outstanding version of Dizzy Gillespie’s “Birks’ Works,” and a blistering outing on “Cherokee,” neither of which appear on any other Montgomery recordings. There are also alternate renditions of three of the best tunes from the Verve set – Miles Davis’s “No Blues,” Montgomery’s “Four on Six,” and John Coltrane’s “Impressions.”

Guitarists will be at work right away transcribing and learning the new choruses Montgomery spins out in nearly six minutes of soloing on “Impressions,” which was considered a landmark when it was first released in the way it showed how a so-called “mainstream” player like Montgomery adapted readily to the modal forms that Coltrane had embraced. And they will be dazzled by the two takes of “Four on Six”– especially the second, which has almost 11 minutes of just what the title of this set promises.

If you’re beginning your Christmas shopping now, you need go no further for your jazz fan friends than these two releases, which will light up their eyes when they are unwrapped, and repay many listenings in 2024.

More:

Gilding these lilies are two other releases of radio airchecks from the same period, featuring great pianists. These will also be issued in the near future — the third volume of Ahmad Jamal’s Emerald City Nights: Live at the Penthouse (Jazz Detective, 2023), covering 1966 through 1968 in recordings from KING-FM, and Les McCann’s Never a Dull Moment!: Live from Coast to Coast,1966-1967 (Resonance, 2023), which contains more material from KING-FM broadcasts, and the reissue of a Village Vanguard date from 1967.

Gilding these lilies are two other releases of radio airchecks from the same period, featuring great pianists. These will also be issued in the near future — the third volume of Ahmad Jamal’s Emerald City Nights: Live at the Penthouse (Jazz Detective, 2023), covering 1966 through 1968 in recordings from KING-FM, and Les McCann’s Never a Dull Moment!: Live from Coast to Coast,1966-1967 (Resonance, 2023), which contains more material from KING-FM broadcasts, and the reissue of a Village Vanguard date from 1967.

All four of these releases (along with the previous two Emerald City Nights collections by Jamal) were spearheaded by Zev Feldman, who made each one a collector’s jewel, with distinctive design reminiscent of the era, excellent photographs, and copious liner notes, including many reminiscences and appreciations from other jazz musicians, transcribed from Feldman’s interviews.

There should be a special place in jazz heaven for producer Richard Seidel, who was one of the chief movers behind Maximum Swing. Seidel has been one of the most active producers in jazz since the late 1970s, championing new recordings by masters like Jimmy Smith (Damn!, Verve, 1995) and Bobby Hutcherson (Wise One, Kind of Blue, 2009), and guiding discovery and reissue projects like Ella Fitzgerald’s Twelve Nights in Hollywood (Verve, 2009), several of the Miles Davis “Bootleg Series” releases on CBS/Sony/Legacy, and the Montgomery-Kelly recordings above. His track record is so impressive that the line “Produced by Richard Seidel” on a jacket is almost a guarantee of high quality. He proves it once again with the restoration of Maximum Swing.

For an informative interview with Seidel and a review of his career, see a post on Doug Payne’s website.

Seidel seems to have found an ideal partner for the Montgomery-Kelly set in restoration engineer Matthew Lutthans, who provides liner notes with a comprehensive description of the arduous process of rectifying numerous flaws in the source tapes. One example will suffice: when Seidel and Lutthans discovered that “a full second of music” was missing from “Cherokee,” Lutthans found four quarter-second snippets from other parts of the tune to fill that hole. I challenge the obsessives out there to identify where the edit was made; I certainly can’t hear it.

But all the producers and engineers on these four releases deserve credit for the usually invisible work of making found music sound as good as it can sound.

Jim Wilke, who hosted and engineered the original KING-FM broadcasts now in the Tjader, Jamal, and McCann sets, was a one-man show, and his work is nothing short of stellar. I know, because like Wilke, I hosted and engineered live jazz broadcasts on WBUR in the 1980s, and the adventure was like art on a tightrope — set up the mics, do a quick sound check, coordinate with the studio, intro the band on the air, and then pray you’ve done a good enough job with mic placement so that you can mix effectively on the fly. I worked in mono, but Wilke worked in stereo, so he had even more of a challenge.

The name George Klabin appears often in the credits to the McCann and Montgomery-Kelly sets on Resonance. He not only founded the label, but remastered some of the recordings, and he was the original engineer for one of the McCann CDs. His devotion to great music and beautiful packaging is praiseworthy.

The name George Klabin appears often in the credits to the McCann and Montgomery-Kelly sets on Resonance. He not only founded the label, but remastered some of the recordings, and he was the original engineer for one of the McCann CDs. His devotion to great music and beautiful packaging is praiseworthy.

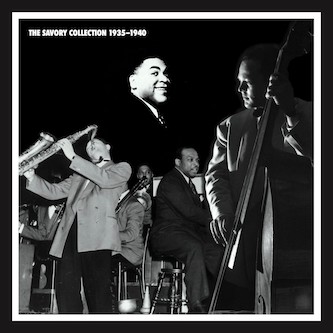

Finally, a nod to a different project from a different era that is also a masterpiece of discovery and restoration. In 2018, Mosaic Records, led by the indefatigable Michael Cuscuna, issued The Savory Collection, 1935-1940, a six-CD set of broadcast recordings captured off air by professional audio engineer Bill Savory. The prize of this set is a full broadcast of Fats Waller’s band in performance from 1938, one of the rare examples of this master of piano, song, and entertainment as he sounded working before a live audience. Here also are many recordings of the Count Basie band with Lester Young, Buck Clayton, and Jo Jones; live broadcasts by John Kirby’s chamber-jazz sextet; and examples of the late 1930s work of Mildred Bailey, Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, Ella Fitzgerald, Stuff Smith, and more. This set was issued in a run limited to 5,000 copies, and it is still available as of this writing from the Mosaic website.

For all his work on Mosaic, which includes a treasure trove of other reissues and reclamations, Cuscuna is, like Seidel (who, BTW, produced Mosaic reissues by Denny Zeitlin and John Handy), one who belongs in the nonexistent Jazz Producers Hall of Fame.

Steve Elman’s more than four decades in New England public radio have included 10 years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host on WBUR in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, 13 years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB.

A small nit to pick in a fantastic piece: Bunny Berigan made “I Can’t Get Started” his own, but credit to the actual songwriters Vernon Duke (music) and Ira Gershwin (lyrics).