Book Review: “The Geography of the Imagination” — Longing for Something Lost

By Vincent Czyz

Touted as “perhaps the last great American polymath,” Guy Davenport had a singular mind; never was an artist more deserving of the MacArthur Foundation’s “genius grant.”

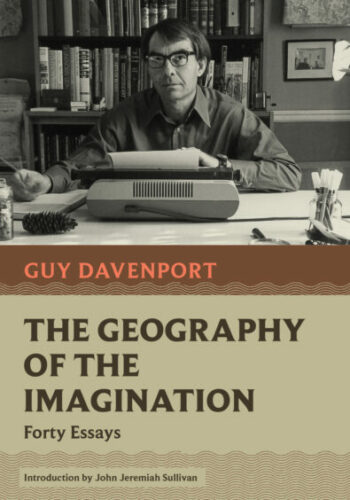

The Geography of the Imagination: Forty Essays by Guy Davenport. I John Jeremiah Sullivan. Godine, 592 pages.

“When a writer does not care about the meaning of a word, we know it. We also know … from his words what he honors, what he is unaware of, and how he modifies with his individual use of it the culture in which he exists.” — Guy Davenport, from “Another Odyssey”

Guy Davenport adored the literary anecdote, calling it “a genre all to itself.” In his essay “Seeing Shelley Plain,” he mentions the Romantic poet William Blake and his wife reading Paradise Lost, naked, in their garden; a young Milton “watching lean Will Shakespeare and fat Ben Jonson staggering home from the Mermaid” (a pub); and, among other tidbits of literary gossip, Marcel Proust and James Joyce sharing a taxi in Paris and battling over keeping one window open (Joyce was claustrophobic) or all of them closed (Proust dreaded a draft of any kind). So it seems only fair to relate one about Davenport: Toward the end of a dinner in a restaurant with a fellow author and said author’s wife, Davenport bare-handedly picked up what was left of his pork chop and slipped it into a pocket of his sportscoat without a hiccup in the conversation or the slightest alteration of facial expression. While it was conceivable Davenport might next scoop up a dollop of his mashed potatoes, his dinner companions telepathically agreed not to hint anything was amiss.

Alas, Davenport departed for the outer limits on January 4, 2005, depriving us of his brilliance (and eccentric table manners). Late to the party, I wrote a tribute to him in 2010, implying — without hyperbole — that his work ranks as a national treasure. Nothing in the intervening years has changed my mind. In fact, the more of his work I read, the more I’m convinced this is the case.

Touted as “perhaps the last great American polymath,” Davenport had a singular mind; never was an artist more deserving of the MacArthur Foundation’s “genius grant.” What remains of that unique way of being in the world includes 10 fiction collections; half a dozen poetry collections, along with assorted translations of Greek poets and philosophers; and at least nine books of nonfiction (primarily essay collections). He was not only, however, a gifted wordsmith, critic, thinker, and translator; he was also a talented visual artist who illustrated his own books and whose drawings and paintings are reproduced in an edition of their own.

It would no doubt be futile to attempt to single out a magnum opus from his impressive oeuvre, but a good case could be made for The Geography of the Imagination. A collection of 40 essays now reissued by Godine, it was a National Book Award finalist in 1982. Little wonder: a Geography is an embarrassment of lyrical, intellectual, and literary riches.

“The imagination,” Davenport writes in the eponymous essay, “that is, the way we shape and use the world, indeed the way we see the world, has geographical boundaries like islands, continents, and countries.” He bemoaned how geographically illiterate we contemporary humans tend to be since this makes us poor readers in a number of adjacent areas. He believed history, for example, could not be separated from geography, and that the present owes it cartographic outlines to the past. “The imagination has a history, as yet unwritten,” Davenport adds, “and it has a geography, as yet only dimly seen.”

Crossing those aforementioned boundaries, Davenport makes connections undreamt of in our quotidian philosophies — between the visual arts and literature, science and the arts, religion and history, music and sculpture, philosophy and creativity, as well as between various other disciplines that lie in needless isolation. The “compartmentalized mind,” as he called it, was one of his perennial foes.

No less important to the collection (or Davenport’s belief system) is the rediscovery of our primal roots. After pointing out, in “The Symbol of the Archaic,” that Modernism, both in painting and literature, hearkened back to the creations of earlier millennia, he writes, “Behind all this passion for the archaic, which is far more pervasive in the arts of our time than can be suggested here, is a longing for something lost, for energies, values, and certainties unwisely abandoned by an industrial age.”

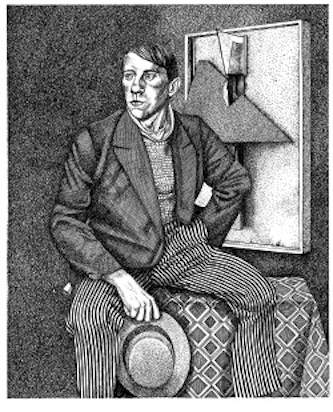

Guy Davenport drawing, from his book Tatlin!

In typical Davenport fashion, this return to a distant past is both point of departure and backdrop for other conceptual claims, such as: while all things are interconnected, art, religion/mythology, and dream are intimately — even inextricably — linked; technology alienates us from the world, while the archaic reconnects us; and everything in a sense is alive. Elaborating on this final assertion, he writes, “In the 17th century we discovered that a drop of water is alive, in the 18th century that all of nature is alive in its discrete particles … and the 20th century discovered that nothing at all is dead, that the material of existence universe is so many little solar systems of light mush …”

Good Heraclitian that he is, Davenport is profoundly interested in change. In “The House That Jack Built” he observes that “To know the seasons we must understand metamorphosis, for things are never still, and never wear the same mask from age to age. The contemporary is without meaning while it is happening: it is a vortex, a whirlpool of action. It is a labyrinth. The clue to this labyrinth … was history.”

In other words, even if we accept that certain archetypal situations repeat over time, the problem of identification remains, since forms undergo alteration and appear in new contexts. Davenport offers a few examples: “The Pequod set out from Joppa [the story of Jonah], the first Thoreau was named Diogenes, Whitman is a contemporary of Socrates, the Spoon River Anthology was first written in Alexandria; for 30 years now our greatest living writer, Eudora Welty, has been rewriting Ovid in Mississippi.” In the tradition of Jorge Luis Borges and Robert Graves, Davenport has a penchant for tracing a motif through space and time: “An Alabama folktale called ‘Orpy and Miss Dicey,’ Cocteau’s Orphée, Monteverdi’s Orfeo, Gluck’s Orphée, Poe’s ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ are all versions of an immemorially ancient pattern of events which sensibilities as diverse as those of Guillaume Apollinaire (‘Zone’ and the Cortège d’Orphée), Anton Donchev (Vreme Razdelno), Rilke (Sonnette an Orpheus), and Eudora Welty were interested to retell.”

It’s a far-ranging collection that subjects an array of historical figures and objects of contemplation to Davenport’s eccentric genius, including Herman Melville, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, Spinoza, Wittgenstein, Charles Olsen, Walt Whitman (we’re also treated to van Gogh’s opinion of Whitman’s poetry), Edgar Allan Poe, Marianne Moore, Wallace Stevens, Louis Zukofsky, Osip Mandelstam, the surreal paintings of Pavel Tchelitchew and Max Ernst, the music of Charles Ives, the labyrinth (“a life symbol of our century”), Greek mythology, and even J.R.R. Tolkien, with whom Davenport took a class.

The collection’s guiding spirit, however, is Ezra Pound. Davenport wrote his PhD dissertation on Pound’s Cantos, considered him the greatest of the 20th century’s creative minds, and in addition to devoting three essays to Pound, relates several anecdotes about the poet, one of which includes Davenport himself. It’s no surprise, then, that Davenport’s essays — dense and compact yet eminently readable and gem-like in their beauty — seem to have been influenced by Pound’s ideogrammatic approach, which called for abstract concepts to be embodied in images. I’d venture a description, but in the midst of discussing the work of John Ruskin, another polymath, Davenport inadvertently did it for me: “Fors is a kind of Victorian prose Cantos, arranging its subjects in ideogrammatic form, shaping them with a poetic sense of imagery, allowing themes to recur in patterns, generating significance, as Pound did, by juxtaposition and the intuition of likenesses among dissimilar and unexpected things.”

Guy Davenport — despite his erudition, there’s nothing dry or academic about his prose.

A key difference between Pound’s Cantos and Davenport’s essays is that the essays sparkle with clarity. The reader may at times be dizzied by a succession of references — Davenport seems to have read everything — but the Internet is an easy cure for this sort of vertigo. Moreover, reading these essays is often plain old fun. Despite Davenport’s erudition, there’s nothing dry or academic about his prose. He has a wonderful sense of humor, knows how to tell a story, and has a gift for picking out details — memorable, striking, or hilarious — as a way of humanizing figures who’ve come to be vaguely mythical. Here’s one such detail: naturalist Louis Agassiz and Henry David Thoreau, whom Agassiz considered a scientist and “one of the few men in America” with whom he could talk, going “exhaustively into the mating of turtles, to the dismay of their host for dinner, Emerson.”

The Geography of the Imagination is a book I often bring with me when I travel because no matter my mood, there’s usually an essay to suit it, and because so many of the essays bear reading a third or even a fourth time. And that’s one of the marks of great literature — even after half a dozen readings, it still holds your attention, and you’re still aha-ing over things you missed the last time around.

“Pound,” Davenport observed, “spent his life looking at art so beautifully made that it cannot deteriorate.” Such art has its corollary in these essays.

Vincent Czyz is the author of Adrift in a Vanishing City, a collection of short fiction that was awarded the Eric Hoffer Award for Best in Small Press; The Christos Mosaic, a novel; and The Three Veils of Ibn Oraybi, a novella. He is the recipient of two fellowships from the NJ Council on the Arts, the W. Faulkner-W. Wisdom Prize for Short Fiction, and the Truman Capote Fellowship at Rutgers University. His work has appeared in many publications, including New England Review, Shenandoah, AGNI, Massachusetts Review, Georgetown Review, Tin House, Tampa Review, Boston Review, and Copper Nickel.

A lovely, persuasive essay about a writer whom, I sadly confess, I have never read. Obviously, my loss.

Thanks, Mr. Peary. I hope you have occasion to read some of his work.