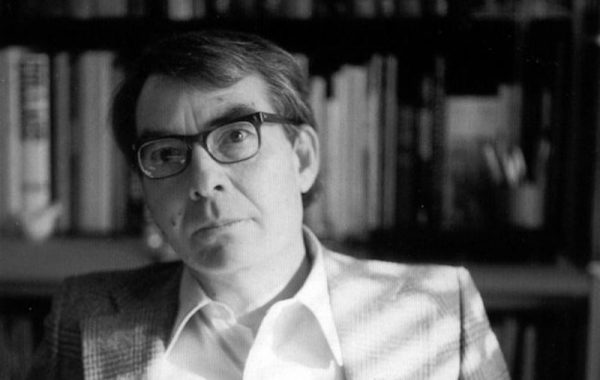

Literary Remembrance: Homage to Guy Davenport — Brilliance Worth Savoring

By Vince Czyz

The 15th anniversary of the death of a grievously neglected American writer whom critics almost universally acclaim a creative genius.

Guy Davenport — time and again, his writing intimates that art possesses a beauty no less astounding than nature’s.

Dropping Guy Davenport’s name, even among the literati, often results in little more than “Sounds familiar …” or “Didn’t he write …?” To me, that is almost as tragic as the loss of the author himself to cancer on January 4, 2005. A MacArthur Foundation Fellow, Davenport bequeathed to us more than half a dozen collections of fiction, several books of essays, two volumes of poetry, assorted translations of Greek poets and philosophers, as well as an edition of drawings and paintings. How to account for the obscurity of a writer whom critics almost universally acclaim a creative genius? America, it seems, long ago lost its taste for the new and unusual in literature and has little patience for work that doesn’t hold itself upright with a backbone of what-happens-next.

Combining structural elements of essay, poetry, and narrative, Davenport virtually reinvents fictive form as he makes forays into various fields — history, aesthetics, physics, botany, philosophy, and religion among them. Made up of fragments, progressing by allusion and inference, his fanciful tales are nonetheless discernible wholes, lyrical mosaics in which language itself is as important as what it conveys.

“All at first was the fremitus of things, the jigget of gnats, drum of the blood, fidget of leaves, shiver of light, boom of the wind.” Here is a handsome illustration of Davenport’s style. I had to look up fremitus, but of course it was implied by the context. Jigget, however, doesn’t show up in any dictionary I could find. But we think of jagged, we think of jiggle and, since we are dealing with gnats, probably settle for jerky flight or perhaps erratic buzz. There are other words of this ilk: bodger, vastation, conder. And words that seem to be neologisms but aren’t (guidon, quitch, awn). Davenport isn’t showing off; he’s having fun — frolicking in language and inviting us to join in.

“C. Musonius Rufus” (out of Da Vinci’s Bicycle, now a New Directions Classic), from which the above line was taken, is one of the most beautifully written short stories I’ve ever read. In one thread of the narrative, Davenport imagines the Roman Emperor Balbinus speaking from the grave: “Then I went down to where iron grows. Down past root seines in loam like condered oakgall and down past yellow marl hard with quartz the splintered ores begin. Green, edged, with the black metal horses hate and wine sours next to, and which thunder has entered. Chill, sacred iron, bitter with lightning.” The dead ruler offers one gorgeous meditation after another while the other thread of the narrative follows the plight of the stoic philosopher Caius Musonius Rufus, who has been sent to a prison camp in Greece.

Da Vinci’s Bicycle is an excellent introduction to Davenport’s impressive oeuvre. Taking historical figures — James Joyce, Richard Nixon, Gertrude Stein, and Robert Walser — as points of departure, often weaving between eras centuries apart, Davenport dazzles page after page. In “Au Tombeau de Charles Fourier” he writes “All of nature is series and pivot, like Pythagoras’ numbers, like the transmutations of light. Give me a sparrow, he said, a leaf, a fish, a wasp, an ox, and I will show you the harmony of its place in its chord, the phrase, the movement, the all.”

Harmony is perhaps the key to entering Davenport’s writing: nothing in existence is separate, each is related, and Davenport not only perceives the connections but also communicates them; they are ours if only we are willing to sit for the performance.

The four longest stories in The Jules Verne Steam Balloon create a sort of novella. Hugo Tvemunding and his girlfriend, Mariana, lead a life both idyllic and ideal: there are simple repasts laid out like still lifes, meticulous descriptions of the meadows and forests through which they wander, innovative and prolonged sexual encounters. Davenport presents, in sumptuous detail, the Greek concept of arête — excellence of mind, body, and spirit. Mariana, addressing Hugo, eloquently sums up this life in “absolute kilter”: “…your eyes fly open at six, you hit the floor like an Olympic champion, hard-on and all … jog three kilometers, swim ten lengths of the gym pool, nip back here for wheatgerm carrot smush while reading Greek, communing with your charming freckle-nosed kammerat Jesus, shower with unreasonable thoroughness while singing hymns, … teach your classes, Latin, gym, and Greek, meet me, bring me back here for wiggling sixtynine on the bed, tongue like an eel … race off and instruct your Boy Scouts in virtue, knots, and nutritive weeds, sprint back here … teach me English while fixing supper, show me slides of Monet and Montaigne …” and, after another roll or two in the hay, it’s time to start all over again.

The collection takes its name from three daimons (“spirits who possess or guide or tempt”) or perhaps three quantum particles (one of them is named Quark) incarnated as young boys who are spotted floating over modern Denmark in an antique balloon. Bearing a message from the Consiliarii, Davenport’s concept of elohim or some other divine council, they are clever, polyglot, and charming.

A Table of Green Fields, a collection of 10 short stories — including a veritable prose poem inspired by a single line from Dorothy Wordsworth’s journal — continues in the vein of The Jules Verne Steam Balloon. Nature, sexuality unimpeded by social constraints, and Davenport’s own tireless wonder, his (implied) insistence that everything we need to be happy is pretty much within arm’s reach, run like currents through this book as well. Fremitus? Indeed, frisson, palpable thrill, sail shook so hard by the wind it sings in a kind of vibrato. Time and again in his writing, Davenport intimates that art possesses a beauty no less astounding than nature’s — he recommends both in large quantities, and woe to him who sacrifices one in the name of the other.

Let Davenport’s writing also be recommended unreservedly. The truth is, if an author like Guy Davenport is allowed to sink into oblivion, then not only is the American soul unlikely to be spared “the inert violence of custom” (Emerson’s phrase), but it’s also unlikely that it’s worth saving.

Vince Czyz is the author of The Christos Mosaic, a novel, and Adrift in a Vanishing City, a collection of short fiction. He is the recipient of the Faulkner Prize for Short Fiction and two NJ Arts Council fellowships. The 2011 Capote Fellow, his work has appeared in many publications, including New England Review, Shenandoah, AGNI, The Massachusetts Review, Georgetown Review, Quiddity, Tampa Review, Boston Review, and Louisiana Literature.

Tagged: A Table of Green Fields, Da Vinci’s Bicycle, Guy Davenport, The Jules Verne Steam Balloon

Two spot on Guy Davenport quotations

Art is always the replacement of indifference by attention.

The poet is at the edge of our consciousness of the world, finding beyond the suspected nothingness which we imagine limits our perception another acre or so of being worth our venturing upon.

Wonderful, these. If I may add a couple companions:

“To notice is to rescue, to redeem.” — James Wood

“Attention, taken to its highest degree, is the same thing as prayer.” — Weil

Thanks Vince, also, for a wonderful remembrance of Guy Davenport. I’ve just read A Table of Green Fields, my first of his books, and am scrambling to find more. Who else writes like this? I discovered Davenport by way of Eliot Weinberger, whose poem-essays bear some resemblance. But I am looking for others…

Thanks for your kind comments, Sam–sorry I am only just seeing them now. I don’t that anybody else writes like Guy although William Gass sometimes comes close. I’d pick up CARTESIAN SONATA. ” Lots of good stuff in there but in particular, “Emma Enters a Sentence of Elizabeth Bishop’s.” It’s the most beautifully written short story I’ve ever read. Move slowly, not much narrative but sentence for sentence hard to beat.

BTW, I’ve always thought love, not prayer, is the highest form of attention. No child ignored by his/her parents feels loved.

Genius! The replacement of indifference by attention! Worthy of a full essay.