Book Review: “The Short End of the Sonnenallee” — A Sure Satiric Brush

By Daniel Gewertz

Cockeyed anecdotes roam merrily through a satiric tale set in an East Germany that’s too larky to be oppressive.

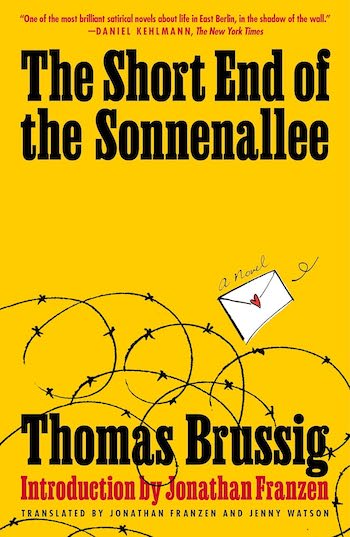

The Short End of the Sonnenallee by Thomas Brussig, translated from the German by Jonathan Franzen and Jenny Watson, with an introduction by Franzen. Picador, 146 pages. Softcover. $16.

It is no easy feat to find the comical in the daily life of the beleaguered East German people, circa 1980. And if those citizens lived literally in the shadow of the Berlin Wall — mere meters from the West — the idea of puckish prose might seem even more ill-chosen. But Thomas Brussig has adroitly turned the trick by focusing on what he knows best: how it felt to be a smart but ditzy teenage boy living in the speciously named GDR — the German Democratic Republic, Russia’s most restrictive satellite nation.

It is no easy feat to find the comical in the daily life of the beleaguered East German people, circa 1980. And if those citizens lived literally in the shadow of the Berlin Wall — mere meters from the West — the idea of puckish prose might seem even more ill-chosen. But Thomas Brussig has adroitly turned the trick by focusing on what he knows best: how it felt to be a smart but ditzy teenage boy living in the speciously named GDR — the German Democratic Republic, Russia’s most restrictive satellite nation.

Such are the facts of life for Brussig’s protagonist, Micha Kuppisch. On the verge of 16, Micha is shy with girls and hopeless about his future: required military conscription isn’t far off, his mother wants him to study in the Soviet Union, and beautiful Miriam, the girl of his dreams, only kisses West German boys. (She contends that Westerners kiss in an altogether different and better way!) Fending off the communist credos and party restrictions that bedevil their lives, Micha and friends cook up their own oddball alternative beliefs as they listen to highly forbidden Rolling Stones and Doors songs, recorded secretly from West Berlin’s pirate radio stations. They sometimes hang out near the Wall, adjacent to a fenced-off area known as “the death strip.” And yet, the novella’s mood remains surprisingly winsome.

Published in Germany in 1999, The Short End of the Sonnenallee has been translated by novelist Jonathan Franzen and Jenny Watson, the former also contributing a glowing introduction. Calling the novella extraordinary, Franzen emphasizes how the story acknowledges East German sorrow but “plays up its ridiculousness.” That is exactly right, though I think Franzen goes overboard when he states that Brussig looks back to his youth with poignance and without “anger or regret: “He sees people being people, the way people have always been and always will be.” I can see Franzen’s point, but I also sense a sad restlessness lurking under the narrative’s droll surface.

The novella’s title, The Short End of the Sonnenallee, refers to Micha’s street, specifically the tiny part of it located east of the Wall. Oddly, a mere 60 meters of the lengthy Sonnenallee exists on the Communist side, so Micha fantasizes that at the Potsdam Conference of 1945 Winston Churchill allowed Stalin this awkward smidgen of the famed street as a way to thank the Russian premier for giving him a light for his burnt-out cigar. “If stupid Churchill had only paid attention to his cigar we’d be living in the West now,” he laments.

Despite the depressing subject, Sonnenallee is a fun, easy read. The most challenging part for a Western reader: at points one is left uncertain of the width of Brussig’s satiric brush. The author wrote the book just nine years after Germany’s reunification, when his German readers could easily recall all the rococo details of their absurd, nearly imprisoned lives behind The Wall.

Take the bizarre school punishment for blemishing the reputation of the state: “a contribution to the discussion” is demanded. Basically, the poor pupil is forced to deliver a short speech to a large student audience about the glories of the state and the party. The theory is that the compulsory speech will transform a scoundrel into a patriot. Micha, excited by a momentary yet very close backstage encounter with Miriam, goes absolutely bonkers with his “contribution” — he becomes insanely euphoric about “the theoreticians of the scientific world view,” and how their love made them “strong and invincible.” The speech resembles a stoned-out, libidinous outburst, and the headmaster is flummoxed for a moment. But then he shouts with fervor: “Yes, indeed! A revolutionary is permitted to be passionate!”

This is a land where criticism is not allowed, but its people are no strangers to the truth. When asked in school how to conduct oneself in the event of an atomic bomb, one nervy student answers: “First: watch, because you’re never going to see a thing like that again. Second: drop to the ground and crawl to the nearest graveyard. But — do it slowly — so as not to create a panic.”

In a country where your next-door-neighbor is as likely to be spying on you as not, hedging your bets is to be expected. The Short End of the Sonnenallee is reminiscent of Catch 22. When caught in an insane society, it pays to be wily, especially when its officials seem more buffoonish than fearsome. (At times, they are reminiscent of Sergeant Schultz in Hogan’s Heroes.) In one scene, Micha and his buddy notice a West Berlin sightseeing bus, the tourists gawking at the miserable East. The two boys clutch their stomachs and shout “We’re hungry! We’re hungry!” When a photo of their misbehavior eventually garners the attention of the authorities, the boys appear to be in legal trouble for giving the GDR a bad name. But Micha retaliates with the perfect subterfuge: raving against the evils of capitalism. He explains they were actually insulting the busload of westerners for their philistine Western beliefs. The routine works perfectly.

Author Thomas Brussig. Photo: courtesy of the artist

The Short End of the Sonnenallee is a short book (137 pages, plus the introduction), mostly a collection of interlocking anecdotes written in an unpretentious, straightforward style. As Franzen points out, the plot doesn’t hew to a precise chronology; it’s more of an exercise in thematic storytelling. One of my fondest characters in Sonnenallee is Uncle Heinz, who lives in West Berlin but frequently visits his relatives in the East. He is always “smuggling” candies and food taped to his body and in his socks and underwear. Micha informs him repeatedly that candy and Gummy Bears are not illegal. But Uncle Heinz’s paranoia is understandable: even East Germans can’t always be certain what counts as a paltry sin and what is a major crime. None of Micha’s friends know why the bland song “Moscow” by the disco band Wonderland could possibly be the most “illegal” song of all time, but somehow it is. The neighborhood’s most fearsome black-market hooligan is the intimidating loner who dares to sell (for a huge profit) mint copies of the Stones’ double album Exile On Main Street.

Micha’s mother, a perfectly paranoid good citizen, proudly reads the official party newspaper. She arranges her mailbox so that neighbors will plainly see the “right” newspaper sticking out of the box. (Their next-door neighbors are thought to be possible members of the Stasi — civilian police informants — because, unlike the rest of the block, they’ve been allowed to own a telephone.) Micha’s disgruntled father rebels by reading the “unofficial” newspaper, which contains the exact same official news, just printed a day later. Generally, the narration sticks close to Brussig’s teenage characters, but I couldn’t help but wonder about the brainwashed lives of the parents. As children, they were proud Nazis. When they reached adolescence they had been transformed into holy believers in the Soviet Union. One assumes that the cultural glories of 19th-century Germany were considered bourgeois corruption.

The boys’ ideas might seem ditzy at first but, set against the mad dictums of the GDR, the teens might have the clearest vision. For example: Micha and friends realize there is no unpolitical subject they can study in college. Architecture? You end up building the exact buildings the government demands. Ancient history? You learn how people in the past were already yearning for “The Party.”

It is revealing that, even while Micha refuses to ingest the fraudulently heroic Communist propaganda, he is still very much a product of his environment. When asked by a friend if he wished to love Miriam or worship her, he chooses to first worship and then die for her.

The grownups seem chastened by authority’s soul-squashing regulations, but some youthful characters are capable of responding with flickers of rebelliousness. Micha’s friend Mario eventually falls in love with a sexy, hip, headstrong girl who is only referred to for several pages as “The Existentialist.” She is like a radical character out of an early Jean-Luc Godard film. Perhaps because Mario has grown up surrounded by “isms,” he falls hard for his new lover’s wacky version of existentialism. At this point, the book tilts quite weirdly via a big scheme that’s way too crazy and wildly theoretical: it’s satire on steroids. Yet, in the midst of this knockabout nuttiness comes a marvelous fairy tale of an ending that symbolically presages the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The book bounds among Micha, his friends, his family members, and his impossible dream girl, Miriam. Cockeyed anecdotes roam merrily through a tale that’s too larky to be oppressive. Somewhere along the way Micha becomes a man: a silly love-struck man, but still a man. The process starts as he struggles successfully with dance lessons; it ends with Miriam teaching Micha how to kiss “like a Westerner.”

Daniel Gewertz has been influenced by the people he has interviewed for newspapers and radio, including jazz artists Ray Charles, Sonny Rollins, Artie Shaw, Dizzy Gillespie, Jay McShann, Gil Evans, Dave Brubeck, Keith Jarrett, Steve Swallow, J.J. Johnson and Milt Jackson; roots musicians B.B. King, Bill Monroe, Brownie McGhee, Vassar Clements, Phil Everly, Roger Miller, Carl Perkins and Bo Diddley; folkies Libba Cotton, Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, Leonard Cohen, Rambling Jack Elliot, Judy Collins, Roger McGuinn, Steve Goodman and John Prine; classic popsters Tony Bennett, Mel Torme, Eartha Kitt and Pearl Bailey; and film/theater artists Louie Malle, Edward Albee, Jeremy Irons, Glenn Close, Susan Anspach, Yul Brynner, Michael Douglas, Diahann Carroll, Jewel, Jack Klugman and John Sayles. Daniel’s first live interview, at age 16, was with Art Garfunkel in 1966.