Book Review: Sofia Coppola’s “Archive” — An Invaluable Exploration of Feminine Creativity

By Paulina Subia

Archive sprang from Sofia Coppola’s desire to record what her mind’s organized chaos says about her and her films.

Sofia Coppola’s Archive, Mack Books, 488 pages, $65.

In one photo, four blonde girls lounge in bed together as they stare into the camera mournfully, perhaps harboring a secret they alone are burdened to carry. A cross rests above their heads — a pink lace bra hangs off of it. In one collage of images, Scarlett Johansson wanders through Tokyo in the rain, looking lost. In another picture, Kirsten Dunst is lying on a baby blue chaise in a 17th-century French palace. She is wearing a white gown and surrounded by pink pastries. The woman we see filming her is dressed in a red Hysteric Glamour T-shirt, a denim skirt, and Adidas sneakers.

In one photo, four blonde girls lounge in bed together as they stare into the camera mournfully, perhaps harboring a secret they alone are burdened to carry. A cross rests above their heads — a pink lace bra hangs off of it. In one collage of images, Scarlett Johansson wanders through Tokyo in the rain, looking lost. In another picture, Kirsten Dunst is lying on a baby blue chaise in a 17th-century French palace. She is wearing a white gown and surrounded by pink pastries. The woman we see filming her is dressed in a red Hysteric Glamour T-shirt, a denim skirt, and Adidas sneakers.

The neon pink cover of Sofia Coppola’s Archive, encased in a baby pink book jacket, is lined with Bruce Weber’s 2000 photo of Coppola’s office at her home in Hollywood. The volume’s intent is to introduce us, pictorially, to one of American cinema’s most fascinating figures, one who is lauded for her talents as both cinematographer and aesthete. Her office is wallpapered with posters and images torn from books and magazines: a compelling image of Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg, a promotional poster for Milk Fed, Coppola’s ’90s clothing line, and a large-scale Kate Moss. Her bookshelves are tantalizingly disorganized, and the floor is covered with discarded boxes, papers, books, and photographs.

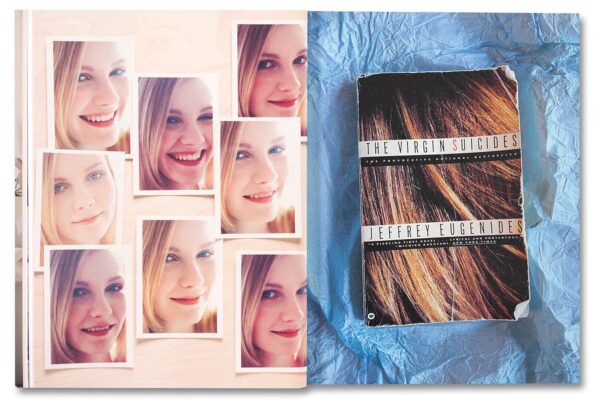

Archive sprang from Coppola’s desire to record what her mind’s organized chaos says about her and her films. In a recent interview, Coppola explained that she fell into the habit of taking photographs while filming her debut, 1999’s The Virgin Suicides. She ended up accumulating photographs and research, all of which had nowhere to go once filming was completed. Unwilling to toss it all away, she saved the material in a box. Over the course of 24 years that became a habit: every film resulted in a personal archive.

Flipping through some of this documentation — annotated film scripts, handwritten notes on stationery cards, abandoned costumes, and piles of reference photographs from bygone eras — may seem self-indulgent. No doubt critics will point out that watching the films should be enough. But the world that Coppola has curated here offers valuable insight into her creations. Her work centers on women’s stories, and it is informative to see how she researches projects that reject the male gaze, that generate research that focuses on the vulnerability of women’s lives, that foster perspectives that go beyond the conventional.

Archive probes the trajectory of Coppola’s storytelling, from her adaptations of existing works of literature to her original screenplays. We are introduced to her characters and are given a chance to watch their growth from inception. The section on The Virgin Suicides makes the awkward clumsiness of teenage girlhood palpable; there are also intimations of how the girls’ lives foreshadow their inevitable deaths. The primary subject (both in Archive and that film) is actress Kirsten Dunst, who, at the age of 16, was described by Coppola in an interview as having “this kind of mysterious depth to her…. She had that unique mix of being an all-American cheerleader … with something deep and complicated going on…. It didn’t really go with her look, but there was more to her.”

The photos, both on- and off-screen, of Dunst selected for Archive display the dualities Coppola notes. She sulks on a lawn chair, laughs as she eats for the camera, poses in a pink bralette, with a tennis racket, and stares over her shoulder while clutching her schoolbooks to her chest. We sense the source of the complexity she brought to her portrait of the infamous Lux Lisbon, a personification of what it means to be a teenage girl — to experience a continual range of emotions, plagued by some unknown sadness witnessed only by her sisters and the four walls of her bedroom.

Archive treats Coppola’s subsequent films as memories from different eras of her life. 2002’s Lost in Translation, arguably Coppola’s most popularly known film, is recalled through snapshots of life-behind-the-scenes while filming in turn-of-century Tokyo. We are given one of Coppola’s handwritten letters to Bill Murray (who plays Bob Harris, essentially a satirical version of himself), pleading that he visit Tokyo and agree to do the film. “The other night at dinner,” she writes to Murray, “some friends tried to cheer me up and help by thinking of other actors if you couldn’t do it. All of the suggestions were so wrong and depressing I broke down in tears at the restaurant (something I never do) and had to leave.”

The section dedicated to 2006’s Marie Antoinette, a film that was ahead of its time given its fusion of romantic aesthetics with modernized language and soundtrack, offers insights into Coppola’s most elaborate project to date: her homage to 2017’s The Beguiled, with its Southern gothic setting revolving around women in a boarding school (a radical retelling of the film’s 1971 counterpart), testifies to the nimbleness of Coppola’s keen eye. It is difficult to overstate how visually stunning the volume’s photos are, particularly as examples of Coppola’s attention to detail. Even the portions of the book dedicated to her lesser-known films‚ including 2010’s Somewhere, 2013’s The Bling Ring, and 2020’s On the Rocks, chronicle her maturation as a visual artist. The final chapter is dedicated to Coppola’s upcoming release Priscilla — a retelling of the life of Priscilla Presley — and its pages suggest the ways that she is returning to, but deepening, her exploration of customary subject matter: girlhood and its trials and tribulations, strained family dynamics, fame and infamy, coming-of-age, and the perils of the rich.

In a letter from Coppola (this one, typed out) to Lady Antonia Fraser, whose biography of Marie Antoinette became the basis for her film, the director writes, “I know I will be able to express how a girl experiences the grandeur of a palace, the clothes, parties, rivals, and ultimately having to grow up. I can identify with her role of coming from a strong family and fighting for her own identity.” This is one of the more personal anecdotes shared in Archive: it offers us a glimpse into Coppola outside of the grandiose visions she creates in her films. Her mission becomes clear: to tell women’s stories, to retain her femininity in a male-dominated community of directors, and to negate allegations of “nepotism.” Some of the photos in Archive are there to make this politically humanizing case: snapshots of her posed behind her camera wearing dresses (“Because that’s not what directors ever wore.… I was determined to still be feminine while directing”), holding her two daughters in between takes, and smiling alongside her cast and crew.

Archive effectively places the director’s emotional life (at least what she reveals of it) alongside her films, encouraging the reader to compare and contrast. This pictorial compendium suggests that Coppola wishes to be remembered within her art.

Paulina Subia is a writer from New Jersey. A recent graduate of Emerson College, where she was the editor-in-chief of Five Cent Sound, she has written for the Boston Globe, Legsville, and more.