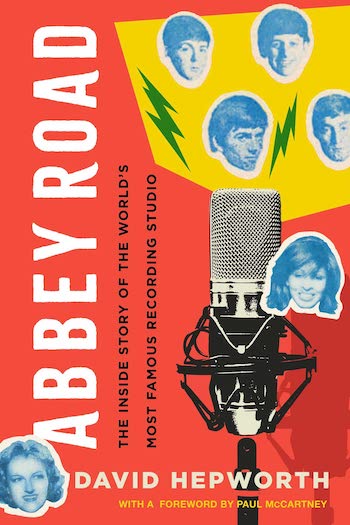

Book Review: The Inside Story of Abbey Road Studio — Definitive

By Adam Ellsworth

The truth is the Beatles wouldn’t have been the Beatles without Abbey Road, and Abbey Road wouldn’t have been Abbey Road without the Beatles.

Abbey Road: The Inside Story of the World’s Most Famous Recording Studio by David Hepworth (with a forward by Paul McCartney). Pegasus Books,416 pages

The recording facility we now know as Abbey Road, opened its doors on November 12, 1931. Sir Edward Elgar conducted the London Symphony Orchestra through his “Land of Hope and Glory” in Studio One, while EMI management, the playwright George Bernard Shaw, and Pathé newsreel cameras watched on.

The recording facility we now know as Abbey Road, opened its doors on November 12, 1931. Sir Edward Elgar conducted the London Symphony Orchestra through his “Land of Hope and Glory” in Studio One, while EMI management, the playwright George Bernard Shaw, and Pathé newsreel cameras watched on.

That was the official opening anyway. Unofficially the studio had already been in use for two months, recording the likes of bass-baritone Paul Robeson and pianist Raie Da Costa. The Black American Robeson, who was in town playing Othello and renting a flat just down the street from No. 3 Abbey Road, recorded Hoagy Charmichael’s “Rockin’ Chair” in September 1931. Three months later, he returned to cut “That’s Why Darkies Were Born.”

Despite its spit take title, “That’s Why Darkies Were Born” is a great song, and, as sung by Robeson, a great record. For David Hepworth, author of the definitive new book Abbey Road: The Inside Story of the World’s Most Famous Recording Studio, it might be the first great record.

“That’s Why Darkies Were Born,” has “an air of uniqueness about it,” Hepworth writes. “This arises from the coming together of one particular artist with one particular song on one particular medium, the 78 rpm record, at one particular moment.” Sure, others had sung the song before, but they were white people in blackface, leaning into the bullshit “ain’t-Black-folk-simple?” surface-reading of the tune. Robeson, on the other hand, was the son of a father born into slavery, so refined he was literally in town to perform Shakespeare. This is how the track was meant to be heard.

“There had always been performers,” Hepworth writes of Robeson’s version. “There had always been songs. But here, suddenly, you had a record.”

As Hepworth proves throughout the book, making records was Abbey Road’s speciality. This is a far more revolutionary concept than it might seem. Even within the building, there were those in the early years who were only concerned with making recordings: faithful reproductions of live musical performances. That was certainly the attitude of the classical music people toiling in the grand Studio One, and their feelings on the matter were not totally without merit. In the first half of the 20th century, even making straight recordings was a challenge. Technological limitations meant everything about a performance had to be perfect from start to finish; if the brass and strings had it nailed, but the percussion was off, there was no option to keep what worked and edit in an improved version of what had been lacking. The whole orchestra had to start again.

Improvements to technology expanded what was possible, and it was the lowly “pop” people working in Studio Two who were most willing to innovate (there was also a Studio Three, which was originally intended for singers and small ensembles). The introduction of the microphone, especially when used by a crooner like Al Bowlly, allowed for intimacy. Magnetic tape, developed by the Germans and only discovered by Britain and America after the Second World War, finally made editing possible, as the poor parts of a performance could literally be cut away, and a more pleasing version inserted in their place. Compression, which Abbey Road engineers picked up by attending American recording sessions, made records sound “punchier, harder, more urgent.”

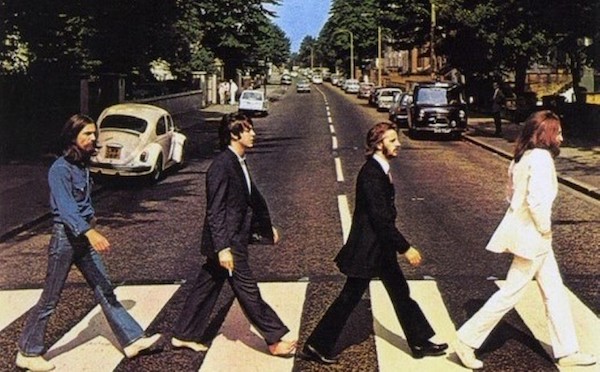

The Beatles outside Abbey Road studios, striking the pose that inspired millions of tourist snapshots. Album cover detail

By the time the Beatles arrived at Abbey Road in 1962, producer George Martin (“Although he liked music well enough, what he really loved were records.”) and his Studio Two lieutenants were ready for them. Hepworth recounts how even the earliest Beatle records benefited from studio wizardry. On “She Loves You,” recorded in July 1963, engineer Norman “Normal” Smith used that still newfangled compression on Paul McCartney’s bass and Ringo Starr’s drums separately, rather than together as had been standard. He also hung a microphone above Ringo’s drums, putting them smack in the center of the sound. This studio magic alone couldn’t make “She Loves You” an exciting record of course. But what it could, and did, do was capture the excitement the Beatles themselves generated and put it on wax.

For the rest of the Beatles’ recording career at Abbey Road, the band brought the ideas and the studio technicians turned their whims into reality. When John Lennon said in 1966 that he wanted his voice to sound like the Dali Lama chanting on a hillside, George Martin sent his vocal through a Leslie speaker. Later that same year, when Lennon said he liked the first part of one take of “Strawberry Fields Forever” and the second part of another take, it was left to Martin and engineers Geoff Emerick and Ken Townsend to figure out that though the takes were in different tempos and different keys, if one were slightly sped up and the other slightly sped down, they would in fact match. The end result was one of the greatest records the Beatles ever released.

There’s a fine line between “those studio folks sure contributed” and “the Beatles would have been nothing without their technical minders,” but Hepworth walks it well. The truth is the Beatles wouldn’t have been the Beatles without Abbey Road, and Abbey Road wouldn’t have been Abbey Road without the Beatles.

This is literally true in the latter case. Before, during, and immediately after the Beatles’ recording career, the facility in which they worked was called “EMI Recording Studios.” Engineer turned studio manager Ken Townsend rechristened the place “Abbey Road” in the mid-’70s as a way to highlight the building’s relationship with its most famous client and their swansong album of the same name. Forevermore, “Abbey Road” would be more than a street that happened to feature a recording studio. For musicians, fans, and historical preservationists, it would be an actual place. A monument to records and the people who created them. A landmark.

Abbey Road Studio. Photo: Wiki Common

Throughout the 21st-century, Abbey Road has profited from its legendary status. Being legendary is in fact its main business model. While still a working recording studio, in a world where anyone with a laptop can make a record in their bedroom, Abbey Road has had to be creative. Enter the Abbey Road Collection of plug-ins, which help those bedroom recordings sound as if they were recorded at Abbey Road by digitally packaging everything from the sound of the facility’s compressor to the room acoustics of Studio Three. If that doesn’t seem quite authentic enough, for 90 pounds, the studio’s mastering engineer Geoff Pesche will master any recording to prepare it for release.

But to skip from the Beatles to the 2000s leaves out too much of Abbey Road’s story, which of course Hepworth doesn’t do. Ample ink is given to Abbey Road-clients Pink Floyd and their 1973 epic Dark Side of the Moon, and to the studio’s partnership with the film sound and music company Anvil, which led to the recording of motion picture scores in Studio One. Even into the late ‘90s, rock bands (rare as they were at the time) like Travis were still coming to Abbey Road to see if they couldn’t capture a bit of the old building’s magic on tape.

All through these years, Abbey Road could still produce a hit. Cockney Rebel’s “Make Me Smile (Come Up and See Me)” for example, is lesser known in the U.S, but it was massive in the U.K., topping the pop charts for two weeks in 1975. When the group’s leader Steve Harley walked into Abbey Road to record it, he brought with him a slow, bitter, kiss off tune, and it was initially recorded as written.

“You might want to try that a bit quicker,” producer Alan Parsons suggested. So the band did, and suddenly, the track started to swing.

“Why not start with the chorus?,” Parsons interjected, a trick that “always occurs to the person listening and never seems to occur to the person playing,” Hepworth rightly notes.

While the point isn’t made in Abbey Road, “try it quicker” and “start with the chorus” are the exact instructions George Martin gave the Beatles during the recording of “Please Please Me” and “A Hard Day’s Night” respectively.

But Parson’s wasn’t done with his proposals. What if Harley put the emphasis on the second line of the chorus, rather than the first? In doing so, the actual name of the song changed from “Come Up and See Me” to “Make Me Smile (Come Up and See Me).”

Before long, the musicians were in on the game. “Let’s get some girls in” was suggested, and suddenly there were female backing vocals.

By this point, the tune had become something very different than the dirge it started out as.

“Musicians like Harley may have gone into the studio to record a dark, bitter song,” Hepworth writes, “but once it became clear that, with a tweak to the tempo and a sunny chorus, they were suddenly dealing with a hit, they forgot their previous agenda and chased it.”

Put another way, when Harley went into Abbey Road, he had a song. When he came out, he had a record.

Adam Ellsworth is a writer, journalist, and amateur professional rock and roll historian. His writing on rock music has appeared on the websites YNE Magazine, KevChino.com, Online Music Reviews, and Metronome Review. His non-rock writing has appeared in the Worcester Telegram and Gazette, on Wakefield Patch, and elsewhere. Adam has an MS in journalism from Boston University and a BA in literature from American University. He grew up in Western Massachusetts, and currently lives with his wife in a suburb of Boston. You can follow Adam on Twitter @adamlz24.