Opera Preview: Expanding “Butterfly”‘s Habitat — A Chat with Phil Chan

By Debra Cash

We’re not saying get rid of “Madama Butterfly.“ We’re saying do a better “Butterfly.”

Phil Chan. Photo: Eli Schmidt

Phil Chan is best known as the ballet dancer who shamed American ballet companies — and eventually, the broader Western dance field — into getting rid of bobbing and shuffling coolie stereotypes in the Tea variation of the second act of the Nutcracker.

In late 2017 he and a colleague, New York City Ballet soloist Georgina Pazcoguin (known as Gina), began to make the case that “yellowface” was no less degrading than blackface minstrelsy, and had no place on 21st-century American dance stages.

Another episode of automatic cancel culture?

Not even close.

Chan argues that classical ballet has been reinvented in every generation as it is passed down as an embodied practice from teacher to student, choreographer to répétiteur. His call was to reinvent it instead of cancel it. It was well overdue, he wrote, “to do a better job of carrying ballet from its Old World foundations into the New World of diverse societies in the 21st century.”

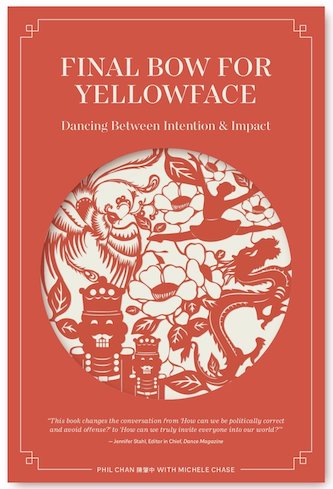

After finding a willing ear in NYCB’s then-director Peter Martins, Chan and Pazcognuin devised a framework for practical activism, asking the directors of ballet companies to sign the Final Bow for Yellowface pledge. It reads: “I love ballet as an art form, and acknowledge that to achieve diversity among our artists, audiences, donors, students, volunteers, and staff requires inclusion. I am committed to eliminating outdated and offensive stereotypes of Asians (Yellowface) on our stages.”

Chan has long lived between cultures as a “both/and.” As he describes in his first book, he is the son of a Chinese-American immigrant who was one of nine siblings raised in a cramped two-bedroom Hong Kong flat. His mother is a white woman from working class Ohio who can trace her ancestry back to the Mayflower. After falling in love at a small rural college in Ohio, the couple moved to Hong Kong, where Phil was born. Right before the 1997 end of British colonial rule in Hong Kong, the family moved to California. He writes:

Having been treated as a White person in the minority my entire life, you can imagine my surprise when, upon arriving to America, I was suddenly labeled a Fresh Off the Boat Chinese minority! It was also the first time I really noticed more than an East/West binary when looking at racial and cultural differences. Berkeley, California was a mix of peoples from all over, and more identity labels than I could keep up with: Hapa. Mixed. Biracial. Gay. Queer. Immigrant. Tall.

Chan’s work stands on the foundation of those spotlit identity categories.

This week, he steps into the most fraught cultural arena yet, that of the canon of Western opera, to reimagine and direct Boston Lyric Opera’s new staging of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly (September 14 through 24 at the Emerson Colonial Theatre). This is an opera whose iconic music is justly cherished but whose “suffering and betrayed child geisha” plot has seemed to many as completely irredeemable.

Chan disagrees. Over the past three years, he has led a remarkable educational initiative at Boston Lyric Opera called The Butterfly Process that brought together historians, musicologists, performers, and community members, asking what do we love about this opera? What’s problematic about this opera? What’s the history and context of this opera? The lectures and conversations ranged from the history of the opera’s production and reception to a discussion of symbolism and female archetypes and an investigation into what goes into professional casting decisions.

Chan disagrees. Over the past three years, he has led a remarkable educational initiative at Boston Lyric Opera called The Butterfly Process that brought together historians, musicologists, performers, and community members, asking what do we love about this opera? What’s problematic about this opera? What’s the history and context of this opera? The lectures and conversations ranged from the history of the opera’s production and reception to a discussion of symbolism and female archetypes and an investigation into what goes into professional casting decisions.

The dive into self-interrogation leans into some of the most salient challenges of American self-definition. Chan and his creative team set the action of Madama Butterfly in San Francisco on the eve of Pearl Harbor, with Butterfly a nightclub performer and Pinkerton an American soldier on the eve of deployment.

I caught up with Phil Chan on Zoom. Our conversation is edited and condensed. I asked him about the initial challenges associated with wrenching a familiar opera from prior expectations to see it anew.

“Final Bow for Yellowface was really a commitment about how we represent nations on stage. In the ballet world that’s traditionally been white people exaggerating Asian features or mannerisms, accents, caricatures, etc. Exotic settings, especially oriental settings, were very, very instrumental in the development of both classical ballet and opera. So the issue with a lot of this work is to take works from the European ballet and opera canon that might have cultural value today. They have beautiful music, beautiful dance. They speak to the human condition but they’re Eurocentric. They’re for Europeans by Europeans from a bygone era.

“The 21st-century American audience, we are not European and we’re not doing anybody favors here by presenting these European works in a European way. Even white Americans are not Europeans, right?

“The problem with Madama Butterfly is not about geishas. A geisha was an artist. It’s actually about the fact that [performing Madama Butterfly] perpetuates ideas about the hyper-sexuality and hyper-submissiveness of Asian-American women or Asian women at a time when Asian-American women are being pushed in front of subways and chased home and being scapegoated for Covid. Puccini could not have imagined that our relationship with Japan or Asian people would be what it is today. Just could not have, right? So, if we want the work to still ring true, we can’t pretend that the most important cultural defining moment between us and Japan is Commodore Perry and the forced opening of Japan and the Meiji restoration. Most people on the street in Boston would say “that’s cool, let’s go get sushi.” We just have a different relationship with Japan than in Puccini’s time.

BLO Artistic Advisor Nina Yoshida Nelsen and Phil Chan at a recent rehearsal for Madama Butterfly. Photo: Kathy Wittman

“As Americans, our most defining time with Japan was World War II: the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Japanese-American incarceration. We still have living memory of that time period, that’s still within living cultural memory. There are still people who are alive today who were incarcerated. So that felt like a congruent setting for the story.

“I had just moderated a conversation with Arthur Dong, who is an incredible filmmaker. He made a film called Forbidden City USA documenting Chinese-American nightclubs in San Francisco from the 1920s to the 1960s. So I thought, what if Butterfly was a jazz singer, an American jazz singer in the ’40s in America?

“As an Asian-American, you know, it’s been bad for the last couple of years. I’ve experienced the uptick in anti-Asianness in our society firsthand. It took just a little disease, you know, that killed all these people, but we were immediately scapegoated. The veneer of acceptance for Asian people is just really so thin. It’s just surface level, and Covid really proved that to a lot of us. And what’s another period of time where we’ve seen that before?

“In the BLO production we haven’t changed the music. But this is how we have to treat works in the canon if we want them to survive. This isn’t radical. If you’ve seen a Shakespearean play with a woman in it, you’re already seeing something radical and different than what was done traditionally [in Shakespeare’s time when all roles were played by men].

“Not every opera company has the resources or the time or the energy or the ability to dive deep like this. We wanted to create an evergreen resource [the Butterfly project website] that was free and available to the public to really keep this work going.

“We’re not saying get rid of Butterfly. We’re saying do a better Butterfly. And I think you’ll get honest performances out of people. You know, human performances, and that’s really what opera is about at the end of the day, right?”

Debra Cash, a Founding Contributing Editor to The Arts Fuse and a member of its Board, is Executive Director of Boston Dance Alliance.

Tagged: Boston-Lyric-Opera, Madama Butterfly

Please also see Pacific Opera Project’s Madama Butterfly in which all Japanese roles are played by people of Japanese ancestry and sing in Japanese, and all American roles are played people of European ancestry and sing in English.

Good to know about this!

Since the BLO performance happened, the artistic leadership of the organization has passed to Nina Yoshida Nelsen. blo.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/BLO-Announces-Artistic-Director-Expanded-Team-copy.pdf