Visual Arts Review: “Edvard Munch: Trembling Earth” — Overwhelming the Clichés

By Peter Walsh

Edvard Munch was very far from a one-hit wonder. His career was a long narrative of restless creativity.

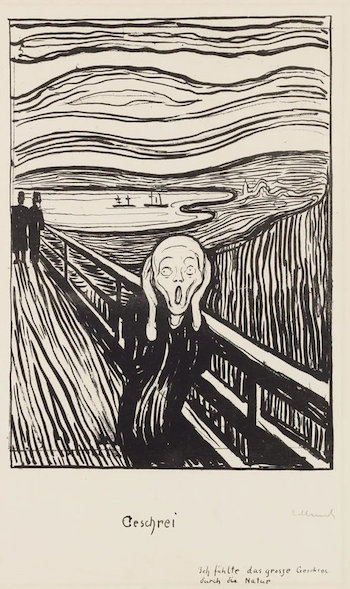

Edvard Munch, “The Scream,” 1895, lithograph on paper. Photo: Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Like all too many so-called “iconic” artists, Norwegian Edvard Munch is best known to the public for a single work that has entered the collective visual consciousness: his relatively early 1893 composition of a solitary figure on a bridge near Oslo, universally known as The Scream, apparently the very model of a modern major panic attack. Munch created five versions of the work: two oil paintings (both in Norwegian museums), two pastels (one of which sold at Sotheby’s in 2012 for almost $120 million), and a lithograph (about four dozen copies were made before the printer resurfaced the stone). Like many celebrity art works, The Scream has been reproduced endless numbers of times: as posters, as lampoons (one featuring an image of Donald Trump), political cartoons, as a deck of cards, a t-shirt, back pack, clock, greeting card, a set of Pokémon cards, a tapestry, coffee mug, neck tie, throw pillow, neon sign, and much else, testifying how deeply, for good or ill, Munch’s image has penetrated into popular culture.

Munch was very far from a one-hit wonder. His career was a long narrative of restless creativity. He was, for example, one of the most innovative, imaginative, and influential printmakers in European modernism. Most of his paintings are, in fact, landscapes, though he is rarely thought of as a landscape painter.

The Clark Art Institute’s superb Edvard Munch: Trembling Earth (through October 12, 2023) is one of those rare exhibitions that can change minds about a long-established major artist. The seventy-five objects chosen for the show include more than thirty from the Munch Museum, Oslo, three self-portraits, carefully chosen prints and drawings, and a stunning group of Munch’s large scale, richly hued landscape paintings. Everything about the exhibition — from the choice of objects to their arrangement to the saturated aubergine, charcoal gray, and midnight blue walls of the galleries — works together to make up a statement so strong that it overwhelms the clichés.

Munch’s childhood was as gothic as The Scream might suggest: a favorite sister died of tuberculosis, a mother with inherited mental illness died of the same disease, a morbidly religious father read his children the stories of Edgar Allan Poe. (“From [my father] I inherited the seeds of madness,” Edvard said later. “The angels of fear, sorrow, and death stood by my side since the day I was born.”) Often in poor mental and physical health himself, Munch said his family suffered under twin curses: consumption and madness.

Nor did things improve much when, as a young man, he decided to become an artist. Everyone — the critics, his father, the neighbors (who sent anonymous letters) tried to talk him out of it. It was only when he left Norway for Germany and France that he found acceptance and success.

Munch came of age in one of those periods when new scientific ideas energize the entire culture. In the late 19th century, the exciting, expanding science was biology, especially as driven by the evolutionary theories of Charles Darwin. Popular books on the theory of life by prominent evolutionary biologists, like the German Ernst Haeckel, whose work Munch knew well, were best sellers. These ideas percolated into new notions about medicine, health, and the endless cycles of life, from birth to the return to the soil after death. They also became major undercurrents in Munch’s art.

As a young artist, Munch played roles in several key art movements: as the first Norwegian “Symbolist,” in German Expressionism, which accepted him as a founding member, and among the “Fauves,” the group of briefly associated French modernists which included Matisse and Braque. All three of these movements focused, generally speaking, on the expression of inner thoughts and emotions over natural visual phenomena: colors could be bright and unnatural, the visual representation of the artist’s feelings, and forms could be flattened and distorted, both to reveal the hidden truths of physical things and to heighten the aesthetic effect.

Edvard Munch, “Beach,” 1904. Photo: Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The first impression on entering the underground galleries of Trembling Earth is of all that brilliant Symbolist-Expressionist-Fauve color — saturated greens against vivid oranges, pinks, and yellows and deep expanses of dark blue. The canvases are large, enveloping the viewer, often in a vertical, “portrait,” format rather than the more typical horizontal, “landscape,” orientation. They give the viewer the impression of looking through a window or an open door, as if Munch’s composition could be entered just by stepping through the frame.

The curators of Trembling Earth have organized the show by theme: “On the Shore,” “Cycles of Nature,” and so on— which may make more sense than a chronological presentation. Munch’s painting style remained more stable than many of his fellow European modernists, without their rapid changes and sudden leaps: Braque into Cubism, Kandinsky into abstraction. The overwhelming impression is of an artist returning again and again to the same themes and places, especially the seashore and countryside near his several homes and studios outside Oslo. It is as if he is determined to squeeze out every shade of nuance and drop of meaning in his subjects.

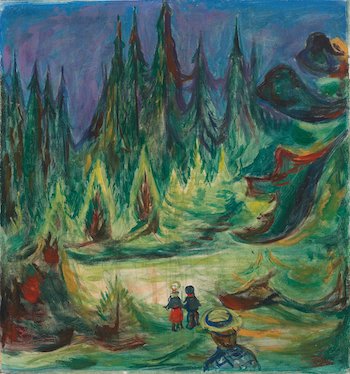

Edvard Munch, “The Fairytale Forest,” 1927–29. Photo: Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A favorite section of mine is “In the Forest.” Several of these paintings return to the theme of small children entering the woods, passing through the towering shapes of trees, sometimes anthropomorphized like Tolkien’s Ents. Munch captures in a momentary image the complicated emotions of innocence walking into a dark and ambiguous wildness — the forest can be either an escape or a source of danger — that is the theme of countless folktales, from Hansel and Gretel to Peter and the Wolf.

The strongest canvases in the show are those that manage, despite their lack of naturalistic detail, to vividly evoke the heightened sense of reality that a particular moment in outdoor space can press upon consciousness. House in the Summer Night (1902) shows the artist’s house and garden in the Norwegian sea coast town of Asgardstrand, a setting for many of his landscapes. Painted in broad, almost expressionist strokes, the painting vividly conveys the magical effect of a deep, starry sky, the ambiguous dark shapes of trees or hills against it, and the cool evening light falling on the garden and side of the house. Years later, Munch repeated the effect in a haunting winter landscape Starry Night (1922-24). In Moonlight (1895) and Summer Night’s Dream (1893), Munch explores the moon reflected across still water, a motif he revised and repeated so often it became a kind of talisman for the visual mysteries of nature. In The Storm (1893) he records the peculiar half light of the clearing sky after a storm in Asgardstrand, the ominous grays contrasting with the warmly lit windows of the houses below it and hanging over the blurred, ghostly figures on the shore.

Munch’s personal distillation of the Zeitgeist’s bio-metaphysics surfaces often. In a series of paintings originally intended as part of a series on the stages of life, Munch transforms naked middle class men on a beach in the German Baltic port of Warnemunde — enjoying the health fad of outdoor nudity as an antidote to the ills of modern urbanized life — into a series of monumental, heroic nudes. In drawings, prints, and a monumental sequence of paintings he presents cycles of life, birth, death, making use of the effects of sunlight, metabolism, and decay to create what resemble charts in a biology textbook. In this universe, everything teems with life and change; nothing is quite inanimate and nature repeats and reflects human anatomy. Hillsides suggest the flow of blood and trees resemble the inner structure of a pair of lungs. In Beach (1904), the weather-rounded, multi-colored boulders along the shore could be living creatures. “In the pale nights, the forms of nature have fantastical shapes,” Munch wrote in a sketchbook. “Stones lie like trolls down by the beach. They move.”

Several sections of the show explore Munch’s innovations in prints, especially woodcuts. Unlike the hardwood blocks used to cut the ubiquitous commercial woodcuts used to illustrate 19th-century newspapers and magazines, Munch’s versions were carved into softwood planks, which he cut with knives to create a printing surface. He often incorporated the natural grain of the wood as part of the design. Once he had cut the composition in the wood, he would saw the block into sections like a jigsaw. This meant he could ink colors on different parts and could switch out parts of the composition, making possible endless expressive variations on a single theme.

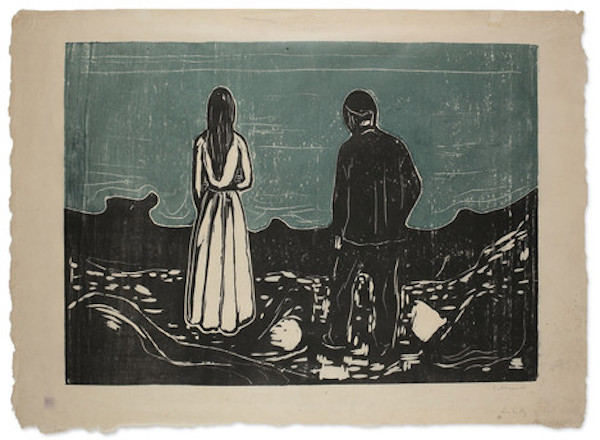

Edvard Munch,”Two People. The Lonely Ones,” 1899. Coloured woodcut from a sawn block in black and grey-blue. Photo: Wiki Common

Among several good examples of Munch’s woodcut technique in the show is his exploration of Two Human Beings: The Lonely Ones (1899). The exhibition includes five variations on this theme, one of his most persistent, which shows a man and a woman from behind, standing on the shore several feet apart, staring out to sea. In different printings, Munch varies the effect dramatically with color, from a dark and almost monochromatic version to ones with a bright pink, slate gray, or deep blue sky. In one, his moon over water motif appears. The woman’s long hair, cascading down her back, changes from red to blond to black.

The Scream makes an appearance, as a monochrome lithograph, in one of these print sections. Compared to the landscapes, it is modestly scaled and not particularly emphasized, hung between two print versions of Anxiety. The lithograph of The Scream includes an inscription in German, translated here as “I felt the great scream through nature.” As originally exhibited, the title of the work was Der Schrei der Natur (The Scream of Nature). Munch recalled that, at sunset, he had felt an “infinite scream passing through nature.” In the context of Munch’s landscapes, his remark suggests the popular interpretation of the image could be all wrong. It is not the figure on the bridge who is screaming, but nature itself. The figure — the stand-in for Munch — simply reacts with the shock of revelation.

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.

Worth the journey to The Clark but a three hour drive (each way).

Very fine review.

I really like his landscapes. I find his figurative works quite disconcerting with so much pain and anxiety on the subjects faces when visible.