Film Review: “The Mother and the Whore” — Not By Words Alone

By Steve Erickson

The Mother and the Whore is a film about failure: its characters are pushed toward misery not only by their own flaws, but by the failure of the 1960s to deliver a promised revolution.

The Mother and the Whore, directed by Jean Eustache. At The Brattle Theatre, September 8 through 11.

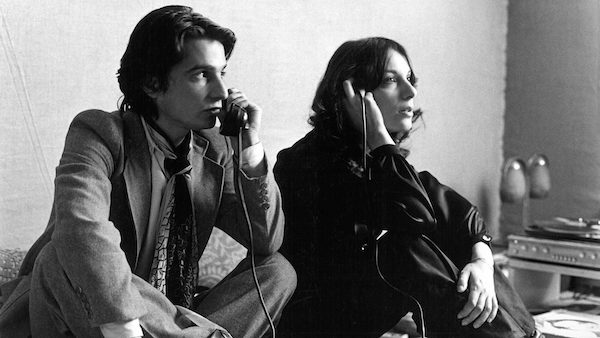

A scene from The Mother and the Whore. Photo: Wiki Common

Actor Jean-Pierre Léaud was 29 when he made The Mother and the Whore in 1973. But, judging by the film, he seems much older than his actual age: not so much in his looks as in a deep world-weariness that is partially covered up by a raging libido. Playing the story’s protagonist, Alexandre, the actor speaks about the recent past as though it took place decades ago. For Alexandre, May ’68 was only five years gone, but he lumps it in with the end of the German occupation in World War II. Although his politics are rather conservative — he is constantly sneering at feminism — Alexandre sings the praises of the ’60s, a time when the Black Panthers, the Cultural Revolution, the Rolling Stones, and May ’68 all seemed to be part of one big liberating phenomenon. He may not be an ideological cheerleader, but the guy still dreams of the morning when he witnessed everyone in a café crying after the police threw a gas canister into the room. Something happened: a crack in an oppressive reality quickly opened, then just as rapidly closed. The Mother and the Whore is a film about failure. On one level, the characters’ struggles reflect the difficult existences led by star Léaud and director Jean Eustache; yet it also exudes a sense that they were pushed toward misery not only by their own flaws but by the failure of the 1960s to deliver a promised revolution.

During Eustache’s 1977 docu-fiction Une sale histoire, its protagonist quotes the Marquis de Sade to the effect that sexual pleasure lies first in hearing, then in seeing. The director spent much of the last few years of his life speaking to strangers on phone chat lines, with the intention of turning the stories he heard into future scripts. Much of what he produced was a much more polite (and less sexual) version of the voyeurism in women’s bathrooms described in Une sale histoire. The Mother and the Whore is a torrent of words that runs nonstop for almost four hours, reportedly based on tape-recorded conversations between Eustache and his lovers. One American stereotype of French cinema claims that it spotlights sex-addicted Parisians sitting in cafes talking about their love lives. The Mother and the Whore takes this accusation to its furthest extreme.

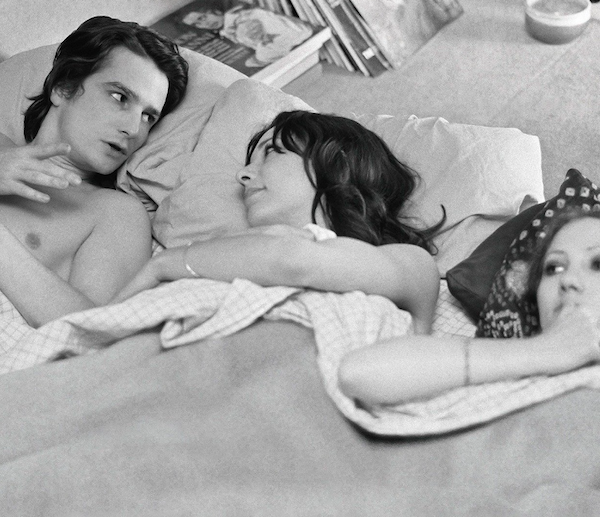

Alexandre (Léaud) and Marie (Bernardette Lafont) live together in her Parisian apartment. She works at a dress shop, while he kills time sitting around in cafés and listening to records with friends. Pining before an ex-girlfriend, Alexandre proposes marriage to her, but she rejects him for another man. At the café Les Deux Magots, he meets Veronika (Françoise Lebrun), a nurse who boasts about her many sexual encounters. They sleep together, with Marie soon discovering his affair. He suggests living together as a threesome, but the relationship collapses into bitter recriminations.

Léaud’s performance and Eustache’s script combine to create a picture of a man who uses words to dramatize himself.

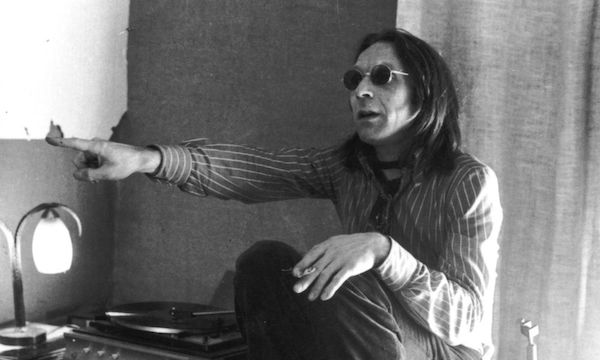

Director Jean Eustache — he recognized how deeply a nerdy form of machismo runs in bohemian subcultures. Photo: Wiki Common

Unemployed, he leeches off his girlfriend while sleeping with other women. This gives him the freedom to hang out with his male friends and Veronika for long sessions of drinking wine or listening to records in the middle of the day. But his brand of liberty amounts to aimlessness. Alexandre’s cinephilia and literacy are drawn on for pretentious mansplaining. (How many people throw out an observation about the transitions from city to country in F.W. Murnau’s films out of the blue on a date?) He’s very impressed with his own intelligence and perceptiveness; he gets more of a buzz from his words than drinking booze. Instead of developing a personality or finding a direction in life — even a very unconventional one — he’s built his existence on posturing. Veronika’s braggadocio, strewn with profanity and “are you shocked?” descriptions of her sex life, mirrors Alexandre’s solipsism, though it’s easier to see through her facade. Both have built themselves up into rebellious characters by repressing their deepest impulses. In the film’s final 90 minutes, the pair come crashing back to earth with an agonizing dramatic intensity. Words finally give way to a scene of Marie listening to an Edith Piaf song silently in real time.

The Mother and the Whore has a reputation of being an early example of right-wing backlash to the counterculture. Many of the film’s defenders value a work that they strongly disagree with, at least politically. And it is true, Eustache gives up the ghost on the liberating potential of the left very quickly. The second half serves up a scathing treatment of the sexual revolution. Still, it is doubtful that the director shares the viewpoints of his characters. The painful incoherence of Veronika’s final monologue — in which she drunkenly regrets sleeping around while protesting the way men view her as a “whore”– suggests a dead end in either ideological direction. Free love didn’t work for this trio, and promises of marriage and motherhood look just as unlikely to lead to a fulfilling life. In this way, Eustache was ahead of his time in recognizing how deeply a nerdy form of machismo runs in bohemian subcultures. In this regard, he was far more perceptive than other French New Wave male directors. If Alexandre were a young man in 2023, one can see him raving about the truths of Michel Houellbecq novels and listening to the reactionary slacker chic of the Red Scare podcast. One of Alexandre’s friends (Jean-Noel Picq) goes even further, flirting with fascism in an ironic-not ironic manner that predicts the authoritarian proclivities of a generation of chronically online young men.

A scene from The Mother and the Whore. Photo: Wiki Common

Several reasons explain why The Mother and the Whore looms so large over Eustache’s relatively scant filmography. Yes, his son Boris’s refusal to license his father’s work for legal release in the US until very recently played a major role in pushing Eustache to the margins. More important may be the fact that he only made one other feature-length narrative film, Mes petits amoreuses. Everything else Eustache made is either a documentary and/or short, and our culture still tends to view such work as less than major. Had he lived past 1982 — and been able to find funding for all the projects he conceived — who knows what Eustache might have made?

In Cinema Scope magazine, Michael Sicinski makes a convincing argument that Eustache turned into an experimental documentarian after 1974. Still, in its own way, The Mother and the Whore breaks the bonds of what a feature-length film is expected to do. As downbeat as it is, the film also laid out a path for personal, if not autobiographical, cinema that Mia Hansen-Løve, Philippe Garrel, Ira Sachs, and Arnaud Desplechin have all extended. If you’re unfamiliar with Eustache, The Mother and the Whore is a great starting point — but it shouldn’t be an end.

Steve Erickson writes about film and music for Gay City News, Slant Magazine, the Nashville Scene, Trouser Press, and other outlets. He also produces electronic music under the tag callinamagician. His latest album, The Bloodshot Eye of Horus, was released in November 2022, and is available to stream here.