Visual Arts Review: In Gloucester, Edward Hopper Became Hopper

By Charles Giuliano

A leitmotif of this exhibition underlines Josephine Nivison Hopper’s role in her husband’s emergence as one of the most successful and beloved artists of his generation.

Edward Hopper, The Mansard Roof, 1923. Photo: The Brooklyn Museum, New York

Gloucester 400+ marks the occasion when white Europeans came to fish. In 1623 men of the Dorchester Company renamed as Gloucester the town explorer Samuel de Champlain (c. 1567–1635) had dubbed Le Beau Port on his 1613 map.

As part of the city’s 400th anniversary, the Cape Ann Museum, in partnership with the Whitney Museum, is presenting the small but exquisite exhibition Edward Hopper & Cape Ann: Illuminating an American Landscape (through October 16). Intentionally or not, yet again his artist wife, Josephine Nivison Hopper (1883-1968), has been snubbed from the naming and branding of an exhibition that would not have been possible without her. The exhibition includes 56 of his works and seven by her.

There is a small gallery of Nivison Hopper’s work, a symbolic “room of her own.” They have never been exhibited in a museum. Of particular interest is a poignant, wan self-portrait in a slip.

When Edward Hopper (1882-1967) died, his widow gave some 3000 items to the Whitney Museum of American Art. It was the largest gift of an artist’s estate to an American museum. Some 300 works by Nivison Hopper were included, but it is unknown how many remain in the permanent collection.

The ravishing CAM exhibition makes the case that during five summers in Gloucester (1912, 1923, 1924, 1926, and 1934), Hopper became Hopper. In 1923, the year before he married Josephine Nivison, he had been an illustrator, etcher, and failed artist. A leitmotif of this exhibition underlines her role in his emergence as one of the most successful and beloved artists of his generation.

Edward Hopper, Jo Painting, 1936. Photo: Whitney Museum of American Art

They were students of Robert Henri (1865-1929) a leading realist painter of the Ashcan school and admired theorist (The Art Spirit). The diminutive Nivison was one of his most respected students. The exhibition contains a remarkable full-length, life-sized portrait by Henri of Miss Josephine Nivison. It portrays her as a commanding presence armed with a fistful of brushes.

The couple, both single and in their early 40s, painted in Gloucester a hundred years ago in the summer of 1923. She was exhibiting in New York while he was surviving as an illustrator. They bonded when he returned her beloved stray cat, Arthur.

It is tempting to say that what followed was a love story. There was surely an aspect of that in their four summers in Gloucester. He had not made a sale in 10 years since he had exhibited a work in the seminal 1913 Armory Show. Now, on the cusp of middle age, it was make or break time for his career. The resulting success caused difficulties in the marriage; there was physical and mental abuse.

Jo changed everything, including Hopper’s style and medium; she also helped launch him in the New York art world through her connections. During an earlier 1912 visit to join his friend Leon Kroll (1884-1974), Hopper had created undistinguished, realist oil paintings, including Briar Neck, Gloucester and Gloucester Harbor, with its clutter of moored schooners.

The exhibit presents the Gloucester of a century ago, when it was a thriving, grungy, odiferous fishing community. In the ’20s the fishing fleet was evolving from sail to diesel; lofts surrounding the harbor provided cheap studios. The Hoppers came as part of a thriving community of artists. The scholarly catalogue by Elliot Bostwick Davis focuses on the work that was produced and provides formal analysis. She supplies rich insights into Hopper’s artistic development, charting the impressive career that sprang from the Gloucester works. Generations of America’s greatest artists have been drawn to Cape Ann because of its proximity to the sea, salty air, and brilliant light. Rent then was cheap. Hopper primarily focused on house portraits, rendering them with crisp precision.

Initially, the Hoppers were too poor to own a car and explore Cape Ann. They stuck close to their lodging and painted the captains’ houses and modest homes of the fishermen of The Fort and Portuguese Hill areas. Those dwellings have since been gentrified and condo developments have been crammed into every vacant lot.

That first summer Jo influenced him to paint with the more portable watercolor. They labored side-by-side, and it is likely that she coached him on technique. Most of the structures they rendered still stand. There are popular walking tours: the museum has published a map of 30 sites. Driving about Cape Ann you can still recognize many potential “Hopper houses.”

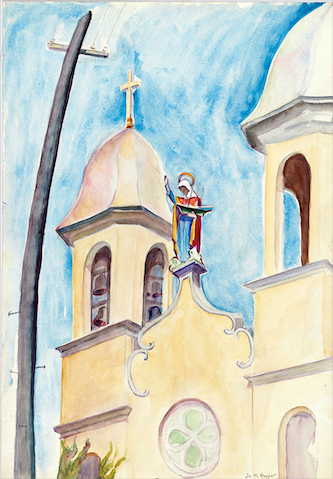

Josephine Nivison Hopper, Church Towers, Gloucester, 1923. Photo: Whitney Museum of American Art

It is interesting to compare and contrast their renderings of the landmark baroque towers that frame the statue of Our Lady of Good Voyage in the exquisite church on Portuguese Hill that bears her name. Her picture renders the facade head on in detail, while his looks at the steeples from a distance.

In the fall of 1923, Jo was invited to exhibit in a biennial survey of American watercolors at the Brooklyn Museum. She was allotted 12 spots and convinced the jurors to assign half of them to Hopper. One of them The Mansard Roof was acquired by the museum for $100. He had a foot in the door, and with her constant, self-sacrificing support, his career and reputation soared.

Despite the recognition, melancholy and ennui pervade Edward Hopper’s work. Its austerity stands in stark contrast with the pot-boiling narratives served up by the prevailing Regionalism and the art of The American Scene. He had no interest in the politics of Social Realism or in the European avant-garde that had been introduced by the Armory Show. While those genres have fallen out of fashion, the loner vision of Hopper prevails.

His wife kept account books of his works with notations, and these are invaluable for research. Jo was also his model and muse. She is a universalized figure in some of his masterpieces. From the work done in Gloucester there is one three-quarter portrait, with a mass of hair, Jo Painting, from 1934.

During the summer of 1924 Jo wanted to visit Provincetown to participate in theater and be with friends. Hopper preferred the varied subject matter of Gloucester to the smooth dunes of the Outer Cape. Jo would submit to returning to Gloucester only if they married. They later moved to a summer home in then sparsely populated Truro.

Inevitably unpeopled, his crisp, brilliantly lit Gloucester houses underscore the precision and austerity of his later work. The vision here is of self-denial, introspection, and a cold Protestant ethic.

The exhibition primarily includes works on paper, which must be displayed under low light. That encourages viewers to stand close and study their subtle surfaces. There are wonders to behold.

It is ironic that Hopper could bring such simple beauty to humble homes. Gloucester Mansion, for example, is anything but, though Mansard Roof, an early masterpiece, is rather grand. There is a plethora of house paintings here to contemplate: Anderson’s House, Parkhurst House, House in the Italian Quarter. There is a single harbor subject, The Trawler.

While in Gloucester with Jo he made only a few oil paintings, but they are truly remarkable. 1928’s Hodgkin’s House is featured on the cover of the elegant catalogue published by Rizzoli. In the gallery the picture explodes off the wall, its brilliant chiaroscuro accenting the structure of the elegant white house on Washington Street.

The barren meadow with boulders, Gloucester Granite, depicts the open space known as Dogtown. John Sloan and others painted it, and it was the exclusive subject of Marsden Hartley during his Gloucester tenure.

Edward Hopper, Freight Cars, Gloucester, 1928. Photo: Addison Gallery of American Art

Arguably, 1928’s Freight Cars, Gloucester is an early masterpiece in this exhibition. It is a picture that captures the essence of the city — Gloucester delivering its fish to market. Only a genius like Hopper could find beauty in such a bleak, generic industrial setting. It also conveys the eccentric oddity of his estranged and mordant vision. This oddly absorbing and powerful work makes the case for this superb exhibition: in Gloucester, Hopper became Hopper.

Charles Giuliano has just published Annisquam: Pip and Me Coming of Age.

Tagged: Edward Hopper, Eliot Bosworth Davis, Gloucester 400+

The Hopper shows just keep coming! Thank you so much for this education, for telling this part of the artist’s story — the adventures of Edward Hopper and Josephine Nivison Hopper — and for enticing us with accounts of a few standout paintings. There are so many! Cannot wait to make the late summer trip. What a perfect time of year to see this work. What a rich review.

An exemplary review–a fusion of context and commentary that illuminates artists and their work. Well done.