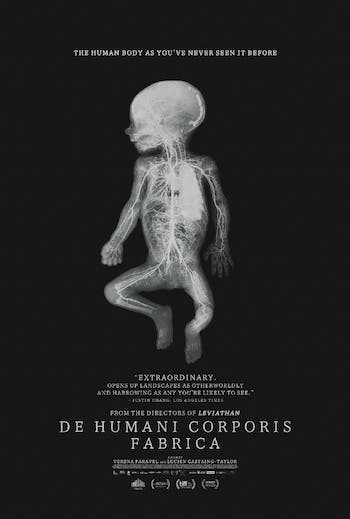

Film Review: “De Humani Corporis Fabrica” — Invasive Procedure

By Peter Keough

Singing the body electric in De Humani Corporis Fabrica.

Since it was established in 2006 by Lucien Castaing-Taylor, Harvard’s Sensory Ethnographic Lab (SEL) has produced some of cinema’s most inventive and challenging documentaries. Their goal, said Castaing-Taylor when I interviewed him in 2014 for Boston magazine, is “to express in propositional prose the sense of the infinite magnitude of human existence that can’t be transcribed.”

Since it was established in 2006 by Lucien Castaing-Taylor, Harvard’s Sensory Ethnographic Lab (SEL) has produced some of cinema’s most inventive and challenging documentaries. Their goal, said Castaing-Taylor when I interviewed him in 2014 for Boston magazine, is “to express in propositional prose the sense of the infinite magnitude of human existence that can’t be transcribed.”

The films have ranged from the pastoral rhapsody of Castaing-Taylor and Ilisa Barbash’s Sweetgrass (2009) to the pathological intensity of Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel’s Caniba (2017), and from the depths of the ocean in Castaing-Taylor and Paravel’s Leviathan (2013) to the innermost secrets of the human body — and soul — in the latter pair’s newest film, the sublime, revolting, giddyingly immersive De Humani Corporis Fabrica (2022; screens July 14-17 at the Brattle Theatre). Shot over the course of seven years in several hospitals in Paris, it takes its title from Andreas Vesalius’s groundbreaking medical textbook published in 1543.

Those secrets are both bluntly graphic and teasingly cryptic. Perhaps they can be discerned in the abstract swirls released in arthroscopic brain surgery, a kind of lava lamp of pink clouds of blood and cotton-candy-like tissue. Or maybe they are somewhere in the 10-minute pan that concludes the film of a fresco, painted on a cafeteria wall, depicting priapic surgeons dancing with skeletons.

A clue might be found in the repeated tracking shots of two old women in the geriatric unit who wander the halls, hand-in-hand, muttering about a man they are trying to avoid. From outside the frame of that shot can be heard a repeated cry like that of a jungle bird — it turns out to be the moaning of an old woman in a hospital johnny. Her cries are echoed in the next sequence by an infant girl who is delivered by means of a brutal-looking caesarean section. The infant is comforted, but the old woman is not. Later, someone who looks like her shows up among the dead lined up on gurneys in the morgue.

Other scenes are more directly assaultive in their depictions of naked humanity, such as the extreme close-up of a penis being aggressively probed by a catheter. Perhaps more disquieting than the image itself is the off-screen chatter of the urologist performing the procedure. He asks if anyone knows the difference between a penis and a phallus and explains that “phallus” refers to the organ in the erect state. He goes on to boast that he has been personally told he has a beautiful phallus. He then complains about being overworked. He is doing about 20 operations a day and, because of his exhaustion, he can’t even manage to get an erection himself anymore. Meanwhile, blood gushes from the penis he has been poking at, an image reminiscent of an especially disturbing moment in Lars Von Trier’s Antichrist (2009).

The background conversations of the medical people often overshadow the stunning images, as when a surgeon talks about real estate prices in a Parisian neighborhood while inserting a lens into the eyeball of a conscious patient. Or, back in the urology department, during a forceps-eye view of a prostate surgery, we overhear random comments like “It’s getting a bit abstract,” “This guy’s weirdly put together,” “His dick is incredibly swollen,” “Clean up your table: It’s a mess!” and, most unnervingly, “What I’m doing is very complicated plus I’m not an expert in the field.” Then the image starts filling up with blood. If you’re a guy visiting Paris and have a peeing problem, it may be best to wait on it until you get back home.

De Humani builds on the observational style with which Frederick Wiseman thrusts viewers into the medical world in films such as Titicut Follies (1967), Near Death (1989), Hospital (1969), and Primate (1974). Intercutting sequences taken from the “scialytic” cameras mounted above operating tables, from MRI and X-ray imagery, from arthroscopic devices, and from their own tiny “lipstick” cameras, Castaing-Taylor and Paravel create an alternately disorienting and clarifying kaleidoscopic anatomy of the medical profession. Sometimes the results suggest a cross between the 1966 film Fantastic Voyage and the avant garde works of filmmaker Stan Brakhage. And, like Wiseman, the filmmakers offer little external direction. Instead they guide the viewer by means of subtle, evocative, sometimes epiphanic editing.

Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel. Photo: Grasshopper Film

As in their astonishing and immersive Leviathan, extreme close-ups and shots taken from odd places and angles sometimes transform what is seen into elegant and sublime abstractions. The penis in what is becoming the film’s most notorious scene is unmistakable, but some of the other images are too ambiguous to be identified right away. Recognition often brings shock and awe. For example, at one point a couple of doctors prod and slice an object that looks like a cut of meat being prepared for some tasty meal on America’s Test Kitchen. They flip it over and the nipple immediately reveals it to be a cancerous breast.

The probings through the bodies’ tissues and vessels are paralleled by similar peregrinations through the physical plant of the hospital, as when the camera follows the voyage of a canister containing lab results through a pneumatic tube or accompanies the patrol of security guards through the graffitied basement corridors. Perhaps the filmmakers are propounding that the hospitals themselves are bodies, structures fabricated to incorporate human needs, relationships, and the tragedy of our existence.

When I interviewed Castaing-Taylor in 2014, he quoted from Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, James Agee’s 1941 book about Depression-era tenant farmers, to explain the purpose of SEL:

“‘The cruel radiance of what is,’” he said. “That’s our goal. To get away from the conventions that constrain and prettify film and to get back to the cruelty of reality.”

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, including Kathryn Bigelow: Interviews (University Press of Mississippi) and, most recently, For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).