Film Review: “Shin Kamen Rider,” “Shin Ultraman,” and Hideaki Anno’s Philosophical Superheroes

By Nicole Veneto

As The Flash crashes and burns at the box office and audiences grow tired of multiverse sagas, creative mastermind Hideaki Anno has delivered two badly needed breaths of fresh air to a genre suffocating under the weight of its own cultural stagnancy.

Shin Ultraman is now available to rent on VoD. Shin Kamen Rider will be available to stream worldwide via Amazon Prime on July 21st.

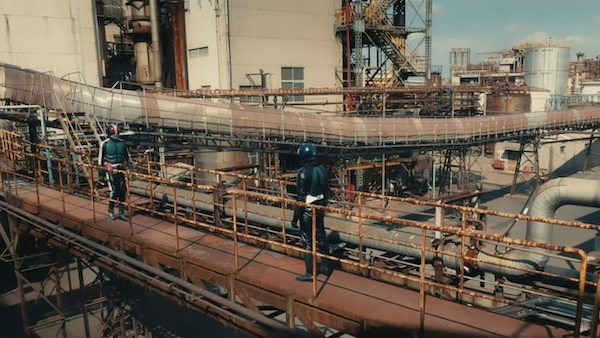

The transformed Takeshi Hongo a.k.a. Kamen Rider (Sosuke Ikematsu) delivers his signature mid-air kick in Shin Kamen Rider. Photo: Toei

Hideaki Anno has more than earned the right to do whatever he wants. The creative mastermind behind Neon Genesis Evangelion didn’t just stick an unprecedented landing with the emotionally-charged finale to his Evangelion reboot tetralogy Evangelion 3.0+1.0: Thrice Upon a Time, but he did so off the back of his politically-charged 2016 Godzilla reboot Shin Godzilla. Released to widespread international acclaim, Shin Godzilla (released as Godzilla Resurgence in the US) was retroactively designated the first entry in the Shin Japan Heroes Universe (SJHU), a collaborative endeavor between Anno’s Studio Khara, Toei, Toho, and Tsuburaya Productions adapting several beloved Japanese tokusatsu franchises to the big screen. Helmed by Anno and several of his Evangelion collaborators (including fellow anime director Shinji Higuchi), the SJHU is more or less a traditional branding opportunity for tie-in marketing than a full fledged cinematic universe a’la the MCU. Apart from a vague — if not deliberately parodic — suggestion of continuity between Shin Godzilla and Shin Ultraman, all of these films are stand-alone entries whose only commonality is Anno’s creative oversight and the moniker of “Shin” (シン) in their titles.

It’s no secret that I’m critical of the current state of cinema, beholden as it is to “realistic” adaptations of comic book IPs and the now used-and-abused conceit of the “multiverse” as a transparent marketing grift yoking every superhero property together. Not even long-standing rivalries between movie studios can prevent the totalizing and financially lucrative impulse towards shared universes — Spider-Man’s joint custody between Sony and Disney’s MCU has resulted in several filmic iterations of the web-slinger who now all get to team up on screen together for the infantile pleasure of undiscerning audiences worldwide. And mind you, this trend towards shared universes isn’t a noble experiment in narrative or cinematic storytelling, but a machine-like money making endeavor that seeks to fatten as many executives’ pockets as possible while the creators who made these superheroes often languish in poverty or worse. It’s exhausting to say the least, especially when they all employ the same overtly insecure lampshading, grating Whedonspeak, and anemic nods to political realism characteristic of every post-9/11 superhero flick since Iron Man inaugurated the whole enterprise in 2008.

The two newest entries in the Shin Japan Heroes Universe, Shin Ultraman (2022) and Shin Kamen Rider (2023), received limited state-side theatrical releases courtesy of Fathom Events this year. Though both are filmic adaptations of beloved and long-running tokusatsu shows in Japan. Neither Ultraman nor Kamen Rider have the same cultural purchase as Evangelion or (and especially) Godzilla in the West, so these films will be the first introduction for many to the character. Despite going in pretty much blind to both movies, my robust working knowledge of Hideaki Anno’s filmography and the various influences he pulled from to create Evangelion meant I wasn’t completely lost at sea. What’s distinctive about both Shin Ultraman and Shin Kamen Rider — when compared to the glut of green-screen dependent capeshit — is not only the tactile craft on display, but Anno’s clarity of vision regarding both of them as a filmmaker and a die-hard fan himself. Both feel like a pre-MCU return to form for superhero movies, spiritually akin to Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man films in their total and unquestioning acceptance of the inherent goofiness of caped crusaders.

Ultraman/Shinji Kaminaga (Takumi Saitoh) mid-battle with an evil alien doppelganger in Shin Ultraman. Photo: Studio Khara

Though Anno bequeathed directing duties to his long-time creative partner Shinji Higuchi to finish work on Evangelion 3.0+1.0, Shin Ultraman is undeniably a Hideaki Anno film. Written, edited, and produced by Anno, Shin Ultraman is a cinematic reimagining of the ’60s Ultraman television series Anno grew up on. (In fact, one of Anno’s earliest director credits was his short fan film Daicon Film’s Return of Ultraman with himself in the titular role.) In the wake of a series of escalating kaiju attacks, the Japanese government forms the S-Class Species Suppression Protocol (SSSP), composed of a team of brilliant agency misfits a’la Shin Godzilla. During one such attack, the SSSP’s reclusive executive strategy officer Shinji Kaminaga (Takumi Saitoh) goes missing trying to rescue a child from the danger area just as a 60 foot tall humanoid alien descends from the sky to miraculously take out the monster. Dubbed “Ultraman” by Shinji’s plucky new partner Hiroko Asami (Masami Nagasawa), the alien being becomes an unlikely ally for humanity against kaiju and an array of extraterrestrial interlopers seeking to manipulate humanity for their own cosmic ends. Unbeknownst to the SSSP however, Ultraman has assumed and merged with Shinji’s identity in order to better understand the inhabitants of earth, having witnessed Shinji sacrifice his own life to save another during the initial kaiju battle.

With Shin Ultraman, Anno and Higuchi tap into a markedly similar approach to the genre that defined post-Batman ‘89 and pre-9/11 comic book adaptations. It’s funny and deliberately campy, in a way Western superhero movies seldom are anymore. Yet the film never loses sight of its own deeply philosophical ruminations on the human condition, ending as it does on a psychedelic bit of soul searching. Anyone with more than a passing familiarity with Hideaki Anno can tell you that his work often painstakingly examines the idea of human connectivity and how we go about understanding ourselves relative to those around us. After Anno was seemingly finished with Evangelion following 1997’s devastating End of Evangelion, he directed a handful of experimental live action features including Love & Pop and Ritual. These were followed by Anno’s first swing at adapting a tokusatsu IP in 2004 with Go Nagai’s Cutie Honey in both life-action form and with the OVA Re: Cutie Honey alongside Higuchi and fellow anime titan Hiroyuki Imaishi (Gurren Lagann, Kill la Kill, and Promare). Shin Kamen Rider, which likewise received a limited theatrical release in the States in May, is yet another live-action reworking of a beloved tokusatsu under Anno’s unique creative eye.

Grasshopper-Aug 02/Hayato Ichimonji (Tasuku Emoto) and Kamen Rider/Takeshi Hongo (Sosuke Ikematsu)facing off in Shin Kamen Rider. Photo: Toei

Though not as outwardly funny as Shin Ultraman (parts of which play as a straight up comedy), the relative seriousness with which Anno treats the source material in Shin Kamen Rider supplies the kind of fun that comes from watching people in silly outfits and monster suits fight each other on Saturday morning television. It’s his own personal riff on “with great power comes great responsibility,” an ethos that once sat at the heart of the superhero genre but has since been set aside in favor of half-hearted neoliberal bromides and empty CGI spectacle. Based on the seventies tokusatsu about a superpowered motorcyclist fused with the DNA of a grasshopper, Shin Kamen Rider wastes no time on a protracted origin story for those of us entirely unfamiliar with the lore. Instead, it chooses to dump viewers immediately into an explosive high-speed chase that ends in a literal bloodbath the likes of which no Marvel movie would ever attempt.

Kidnapped by the organization SHOCKER and transformed into a synthetic animal hybrid (called Augments, or Augs), motorcyclist Takeshi Hongo (Sosuke Ikematsu) breaks from containment with the help of Ruriko Midorikawa (Minami Hamabe, practically the film’s second protagonist), daughter of the project’s lead scientist (cult Japanese director Shinya Tsukamoto). who have turned on the organization and their plans to subjugate mankind. For his betrayal, Dr. Midorikawa is brutally murdered by one of SHOCKER’s augmented agents, Spider Aug, inspiring Hongo to take up the mantle of Kamen Rider — or “Masked Rider” — to protect humanity from SHOCKER. As Hongo grapples with how to use his newly acquired powers for good, he must battle an ascending murderer’s row of fellow insect-themed Augs and even his own replacement within the organization (a brainwashed photojournalist played by Tasuku Emoto).

Like Shin Ultraman, Anno’s work on Shin Kamen Rider feels like a joyously earned bit of self-indulgence with one of his childhood heroes. (He initially proposed the project to Toei executives during the grueling and emotionally draining production of Evangelion 3.0: You Can (Not) Redo.) His trademark wacky camera angles are ingeniously employed here to shoot the action, especially Kamen Rider’s signature aerial jump-kicks, shot from below as actors/stunt doubles bounce around on a trampoline. His commitment to capturing the tactility of action extends to his use of CG effects to heighten the artifice, oftentimes slowing down the framerate to give it a deliberately unreal effect. This strategy also reflects that these are considerably lower budget films than those from Marvel and DC, which waste mega-amounts to look like video game cutscenes that make your eyes slide back into your skull. There’s a motorcycle chase towards the climax of Shin Kamen Rider that might be the most thrilling thing any superhero movie has attempted in at least a decade. And even when things start to look a little rubbery, the unapologetic absurdity with which it all plays out never fails to keep your attention.

As The Flash crashes and burns at the box office and audiences grow increasingly tired of multiverse sagas (unless they’re made by a bunch of exploited animators in an unsustainable work environment of course), Hideaki Anno has supplied two badly needed breaths of fresh air to a genre that’s suffocating under the weight of its own cultural stagnancy. Both Shin Ultraman and Shin Kamen Rider offer an alternate template when it comes to adapting comic book heroes for contemporary audiences. It is a model that doesn’t doesn’t shy away from the giddy absurdity comic book superheroes were once synonymous with. Considering the cycle of hype superhero movies trade in, it’s unlikely that a couple of critical and financial bombs like The Flash or Ant Man: Quantamania will steer Hollywood away from multiverses anytime soon. But Shin Ultraman and Shin Kamen Rider conclusively prove that all you need to entertain is genuine artistic vision and boundless enthusiasm.

Nicole Veneto graduated from Brandeis University with an MA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, concentrating on feminist media studies. Her writing has been featured in MAI Feminism & Visual Culture, Film Matters Magazine, and Boston University’s Hoochie Reader. She’s the co-host of the new podcast Marvelous! Or, the Death of Cinema. You can follow her on Letterboxd and Twitter @kuntsuragi as well as on Substack.

Tagged: Hideaki Anno, Shin Japan Heroes Universe, Shin Kamen Rider, Shin Ultraman, Shinji Higuchi, Studio Khara, Toei, Toho

I grew up watching both series, despite not living in Japan.

The Shin Trilogy is indeed a breath of fresh air, while keeping that lovely uncanny feeling I also felt as a kid when watching the series.