Book Review: “Betye Saar: Heart of a Wanderer” — Sort of a Shaman

By Peter Walsh

Betye Saar’s assemblages and travel sketchbooks are rich in references and symbols; they are mysterious and introspective, more spiritual than political, inspired more by the artist’s world travels than by the struggles of the African-American diaspora.

Betye Saar: Heart of a Wanderer, edited by Diana Seave Greenwald. Princeton University Press, 208 pages, $45.

I met Betye Saar in the ‘70s when she visited my college Art Department. Female African-American artists were rare in those days — she was the only one I remember from my undergraduate days. I remember her as pleasant, articulate, academically trained, and approachable — qualities that softened the shock of her work, known then for its assemblages, like The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972), built out of advertising material and folk art that fixed African Americans in stereotyped images to market products and racist memes. These works were shocking, with an edge of bitter humor that was only sharpened as racist corporate trademarks lingered on for decades to come, “woke” long before woke was a meme.

The Saar works illustrated in Betye Saar: Heart of a Wanderer, catalogue to an exhibition at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum of the same name and companion to the exhibition and catalogue Fellow Wanderer: Isabella’s Travel Albums, are very different: rich in references and symbols, mysterious and introspective, more spiritual than political, inspired more by Saar’s world travels than by the struggles of the African-American diaspora. They also reveal her artistic sources: Southern California assemblage, which rocks between the naive and the sophisticated; Simon Rodia’s Watts Towers, constructed over many years in the neighborhood where her grandparents lived; Joseph Cornell’s “boxes,” which she saw in an exhibition in her home town of Pasadena; and her extensive travels, seeking out new ways of looking at the world.

In a 1994 lecture at the Gardner, during her residency at the museum, Saar remarked, “When you first walk into this place you’re sort of overwhelmed by all the things you see. This lady liked to collect.… She collected fine art, plants, all sorts of things. Her tastes were very eclectic. But there were certain things that I gravitated to. They were mostly the pieces that seemed to relate to my assemblages.” Saar was not so much talking about the great works of European art Gardner had brought to her Boston palazzo but the way she arranged less significant objects in the museum’s galleries. Saar described a cabinet in Gardner’s Early Italian Room: “It’s very interesting because it’s so much like the way I do work balancing things… getting smaller and smaller to the top. As this gorgeous, gold colored cord that’s draped down. The cord is attached to a scroll holder…. And it rests under a Japanese temple table. That has mother-of-pearl inlay on that. And on top of that is a sculpture of the Chinese poet [Li Po], and it’s Japanese pottery. It’s sort of like an international piece that showed what her journeys were, where her trips were. And things that she was attracted to.”

Saar traveled even more extensively than Gardner, to places — like China, Japan, Italy, Egypt, and Mexico — that Gardner also visited, but also to countries in South America, Africa, Asia, and Oceania in which Gardner never showed an interest — but in very different circumstances and with markedly different intentions. As the pages of Fellow Wanderer reveal, Gardner traveled in a cocoon of the most elite white privilege imaginable. When she visited countries outside Europe and North America, it was only to places under European or American imperial control. She stayed in villas built by wealthy American Gilded Age merchants or at English consular mansions, dined with colonial governors or on elegant French food carried to famous ruins by a host of native bearers and guides, socialized with wealthy friends from home, and rarely strayed far from established itineraries for the posher Western tourists. Gardner traveled partly to escape personal tragedy and gossip, to collect experiences, not works of art (which were mostly acquired remotely through agents and at a later stage of her life). The monuments she visited were typically centuries old, belonging to periods before the invasion of European merchants and their armies. The lives of the living non-Westerners she encountered were apparently of no more than passing interest to her because she says next to nothing about them.

Saar’s travels were of a very different kind. Gardner seems to have traveled to reinforce her sense of self, as a woman of wealth, taste, and privilege set apart from the ordinary and the common. Saar seems to travel partly to lose her identity, as an African American, as a middle-class academic, but not as an artist. In a 2021 interview quoted in Heart of a Wanderer she says, “I love to get off a plane at a place and I don’t understand the language…. I don’t understand why they dress [the way they do]. Right away I’m in an adventure.” African Americans are born into an identity they did not choose and cannot easily escape within the United States, no matter how successful, wealthy, or prominent they become. The ability to change the identity of one’s birth, for an evening or a lifetime, is one of the most powerful and least appreciated aspects of white privilege.

Betye Saar, Mystic Sky with Self Portrait, 1992. Photo: Invaluable

In her catalogue essay, Stephanie Sparling Williams writes: “Black artists and intellectuals, for centuries, have discussed travel as a way of escaping the racism experienced in the United States and the colonies, a way of existing in their bodies differently just by changing their geographical context.” The process can seem magical, transformational, liberating. “I have crossed three thousand miles of the perilous deep,” Frederick Douglass writes of his 1845 voyage, as an escaped slave, to Ireland and Great Britain. “Instead of a democratic government, I am under a monarchical government. Instead of the bright, blue sky of America, I am covered with the soft, grey fog of the Emerald Isle. I breathe, and lo! the chattel becomes a man.”

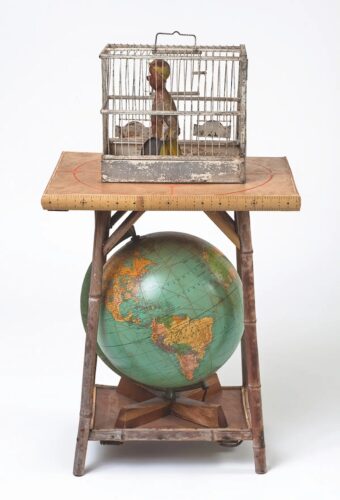

Throughout her travels, Gardner never lost the identity of wealth and privilege she was born with. She traveled only to places controlled by European powers, where a path had already been laid out for her, avoiding South America, sub-Saharan Africa, Central Asia, and Oceania altogether. Saar, in contrast, has visited every continent except Antarctica and always as a collector and artist, avidly acquiring both experiences and things, bringing objects back from Brazil, China, Cuba, Egypt, France, Greece, Guatemala, Haiti, Italy, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, the Philippines, Senegal, Spain, Taiwan, and Thailand. Back home, in works like Visionary (1994), Blue Vision at the Villa (1994) and House of Ancient Memory (1989), she mixes symbols, decorative motifs, colors, and images from several cultures into a single work.

Betye Saar’s assemblage Globe Trotter, 2007. Courtesy of Betye Saar and Roberts Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest

Heart of a Wanderer begins with three essays, by Diana Seave Greenwald, Stephanie Sparling Williams, and Makeda Best. All have illuminating things to say about Saar’s career and the sources of her art, though all also tend to exaggerate the relationship between Gardner and Saar. There has been a tendency lately to recast Gardner as a kind of proto-feminist when, despite her uniquely original creation of the Gardner museum, she remained throughout her life imprisoned in her wealth, her social class, her narrow social circle, and her many privileges. Saar, in contrast, grew up African American during the crucial years of the Civil Rights Movement, and shaped her career in ’60s California, where openness to exotic cultures and unconventional ideas was increasingly the norm.

The book devotes most of its pages, though, to Saar’s assemblages and travel sketchbooks. The contrast with Gardner’s travel albums could hardly be stronger. Gardner’s are almost monochromatic and oddly impersonal, consisting mostly of standard, commercially produced photographs of tourist sites. They reveal little of Gardner’s own thoughts and reactions to what she saw and experienced. Saar’s travel pages are drenched in brilliant color that covers every inch. She leaves none of her collaged images untouched and unmodified. The rich blues, greens, magentas, and persimmons, painted under and over the found imagery, suggest the tented markets of some distant, undiscovered land.

“I suppose I consider myself as some sort of shaman,” Saar reflects in an undated artist’s statement in a Saar archive in Los Angeles, suggesting the underlying magical and spiritual element of the travel work, “one who mixes and transforms information into another form.”

Peter Walsh has worked as a staff member or consultant to such museums as the Harvard Art Museums, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and the Boston Athenaeum. He has published in American and European newspapers, journals, and in scholarly anthologies and has lectured at MIT, in New York, Milan, London, Los Angeles and many other venues. In recent years, he began a career as an actor and has since worked on more than 100 projects, including theater, national television, and award-winning films. He is completing a novel set in the 1960s.

Tagged: Betye Saar, Betye Saar: Heart of a Wanderer, Diana Seave Greenwald