Film Reviews: “Past Lives” and “Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse” — Jorge Luis Borges Was There First

Multiplication and division in two disparate films (and one short story)

By Peter Keough

Past Lives directed by Celine Song. Opens June 8 at the AMC Boston Common 19 and the Kendall Square Cinema.

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse directed by Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers, and Justin K. Thompson. At the AMC Boston Common 19, the Kendall Square Cinema, and the suburbs.

A scene from Celine Song’s Past Lives.

Inyeon, the Korean Buddhist notion of reincarnation that recurs in Celine Song’s Past Lives, and the multiverse, the physics hypothesis that underlies Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers, and Justin K. Thompson’s Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, might be seen, respectively, as temporal and spatial variations on the same idea. In both films these concepts epitomize their themes of fate, responsibility, and individuality — as well as embody the nature of storytelling itself.

Song’s film, a strong debut feature with the occasional staginess that reveals her playwright origins, starts out with off-screen voices speculating about the relationships between three people — a Korean man, a Korean woman, and a white man, each in their 30s — conversing at a New York City bar. These anonymous voices are stymied in their attempt to figure this out, give up, and are never heard from again.

But Song takes us on a flashback to 24 years before in Seoul where two 12-year-olds — Na Young (Moon Seung-ah ), an overachieving schoolgirl, and Hae Sung (Leem Seung-min), her slower but surer would-be swain, play around a whimsical sculpture in the park as their mothers comment on how good they look together. Sadly, they are about to part, because Na Young’s filmmaker father feels there are greener pastures for his profession in Toronto.

Of the two, Na Young is the less brokenhearted; like her parents, she sees more opportunities for her ambitions in the West — as she tells Hae Sung, living there she’ll have a better chance of winning the Nobel Prize for literature. While her parents prepare passports and ask their two daughters (what happens to her sister? We never find out) what new anglicized names they want in Canada Leonard Cohen’s “Hey, That’s No Way To Say Goodbye” plays in the background.

Flash back — or forward — a dozen years and Na Young — now Nora (Greta Lee, who appears in the post-credit cookie scene in Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse as “Interesting Person #2) — has moved to New York. Mirroring Song’s career, she has started writing plays and receives praise from her peers in a workshop.

Hae Sung (Teo Yoo, last seen in Decision to Leave) has taken a more lumpen route. While on maneuvers during military service, later attending engineering school and hanging out with his bros at the noodle shop, he broods over his lost childhood sweetheart, a habit his pals tease him about in drinking bouts that are like outtakes from the early bar scenes in Return to Seoul.

Nora, however, has moved on — though when Hae Sung’s name comes up in a conversation with her mother she looks him up online and discovers that he has been searching for her. They set up a long distance video chat relationship (a kind of uneasy conjoining of Nora Ephron’s You’ve Got Mail and Tsai Ming-liang’s What Time Is It There?), grow closer, until Nora, acknowledging the barriers of time and distance separating them but not showing much enthusiasm in overcoming these obstacles, breaks it off.

Another 12-year flash-forward follows and we’re in the present day, leading up to, presumably, the scene of three people in the bar and the generic voice-overs trying to establish their story. Nora has been accepted at the artists retreat at Montauk where she meets Arthur (John Magaro, heartbreaking in Kelly Reichardt’s First Cow), another resident, and it is to him she explains the concept of inyeon, about how every chance meeting, such as theirs, has recurred over innumerable past incarnations, a process no doubt facilitated these days by the proliferation of social media. Nonetheless, it takes some 8,000 such lifetimes to set up a couple properly for marriage (and you thought online dating was rough). When asked, Nora assures Arthur that such is not the case with them. But she does not factor in the weird dynamics of relationships in a writers retreat or the challenges of finding an apartment in New York City. As for Hae Sung, it looks like better luck next time.

A scene from Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse.

In Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse, the more hectic, mainstream, and vastly more inventive of these two films, an explanation of the multiverse that is the “Spider-Verse” does not come until about two hours into its 140-minute length. This happens in Nueva York on Earth-928, home of the Spider Society HQ where the elite Spider-Men from every dimension meet and are assigned to correct deviations from the orderly function of the limitless Spider-Person network. The explanation comes from Miguel O’Hara, a.k.a. Spider-Man 2099 (played by Oscar Isaac, who describes his character as “the one Spider-Man that doesn’t have a sense of humor”). The multiverse unfolds, he says, as an endless web of interconnections, some of which coalesce into nodes that become part of the “canon” of the Spider-Man universe and thus are ineluctable in every iteration. To try and stop any of these events from occurring will end up in unraveling the Spider-Verse, kind of like the grandfather paradox in time-travel lore. Perhaps more importantly, it will surely piss off legions of MCU fanboys because the “canon” is as much an axiom of comic book narrative tradition as it is a cosmological principle.

This is bad news for Miles Morales (Shameik Moore), the Brooklyn 15-year-old who’s gone the radioactive spider bite route to become his version of Spider-Man (as related in the previous film, 2018’s Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse). In every retelling of the webslinger saga, a key canonical node is the protagonist losing a loved one despite — or because of — his or her attempts to save them. That is also is Miles’s fate — and if he tries to alter it, well, that’s another story to be seen in the sequel Spider-Man: Beyond the Spider-Verse, expected next year.

Meanwhile, there’s plenty to work with in this vertiginous, cyclonic, kaleidoscopic collage. The filmmakers employ a hybrid of CGI and animation which is supposed to make the viewer feel like they have entered a comic book. It is much more immersive and challenging than that, as the frame is inundated with a multiverse of images from not just the Spider-Man and Marvel realms — it is like a comic book palimpsest — but also from cinema and art history. Miles’s nemesis “The Spot,” for example, combines motifs from Basquiat, Yayoi Kusama, Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son, and the Sea of Holes in Yellow Submarine, while voiced by Jason Schwartzman with sublime nerdiness.

The premise may seem familiar after last year’s Oscar-winning Everything Everywhere All at Once, in which our banal world of dry-cleaning and IRS returns is just one of infinite possibilities in countless alternate universes. It also bears resemblance, as mentioned above, to the intersecting network of transmigrating souls posited in Past Lives.

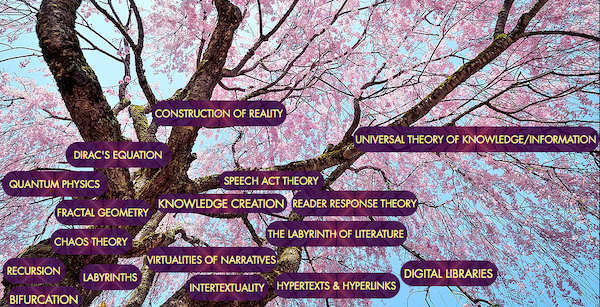

A hypertext that celebrates Jorge Luis Borges and his story “The Garden of the Forking Paths.”

And both films recall Jorge Luis Borges’s 1941 story “The Garden of the Forking Paths,” in which a garden is a labyrinth and a book, “an enormous guessing game, or parable…

…a picture, incomplete yet not false, of the universe … an infinite series of times, in a dizzily growing, ever spreading network of diverging, converging and parallel times. This web of time — the strands of which approach one another, bifurcate, intersect or ignore each other through the centuries — embraces every possibility. We do not exist in most of them. In some you exist and not I, while in others I do, and you do not, and in yet others both of us exist.”

It is also — in both of the films and in the story — a plot device, with Borges providing the consummate twist of making it a device in an actual espionage plot.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

Tagged: Celine Song, Joaquim Dos Santos, Justin K. Thompson, Kemp Powers, Past Lives, Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse