Opera Album Review: Jonathan Berger’s “Mỹ Lai” — A Miniature Masterpiece

By Ralph P. Locke

Jonathan Berger’s remarkable chamber opera about the Mỹ Lai Massacre is a powerful artistic and antiwar statement.

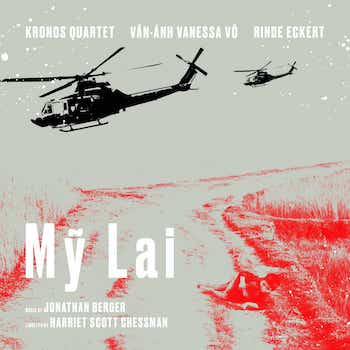

Mỹ Lai: Jonathan Berger (music) and Harriet Scott Chessman (libretto)

Rinde Eckert (tenor), Vân Ánh Vanessa Võ (đàn t’rưng, đàn bầu, and đàn tranh), Kronos Quartet.

Smithsonian Folkways 40251—70 minutes.

To purchase or listen, click here.

“The cruel war is raging,” sang Peter, Paul, and Mary in 1962. I — a future music historian and critic — was only 13. The future composer Jonathan Berger (born 1954) was 8, and Harriet Scott Chessman (born 1951), librettist for Berger’s remarkable short opera Mỹ Lai, was 11.

“The cruel war is raging,” sang Peter, Paul, and Mary in 1962. I — a future music historian and critic — was only 13. The future composer Jonathan Berger (born 1954) was 8, and Harriet Scott Chessman (born 1951), librettist for Berger’s remarkable short opera Mỹ Lai, was 11.

The cruel war was of course in Vietnam; it had begun in 1955, and it continued, expanding into Cambodia (with Nixon’s secret bombing campaign) and it also destabilized Laos, until American troops were finally withdrawn in 1975. The war was cruel beyond what the American public was told at the time or was allowed to see on TV. It was finally revealed also as misguided, counterproductive (if the aim was to block communism), and sadistic (as war so often is). Not least, it was exploited for domestic political purposes in the United States. We American voters are often urged to express our patriotism by supporting our government’s current foreign war-of-choice, no matter what.

One of the first moments when the public began to grasp what was being done with our (or our parents’) tax dollars came when New York Times reporter Seymour Hersh published his exposé of the massacre at Mỹ Lai (I use the Vietnamese spelling, with the tilde over the y) and when army photographer Ron Haeberle’s horrifying photos of the many dead bodies of noncombatants (mostly women, children, and the aged) began to circulate. Composer Berger recalls, “I was 15 at the time. The chilling depiction and images comprised my political awakening, leading me to spend a good deal of my high school years, guitar in hand, at anti-war demonstrations haunted by the horrific images of the carnage.”

Mỹ Lai (first performed in Chicago in 2015 and here recorded for the first time) is a 70-minute long monodrama — that is, an opera for one singer — accompanied by the renowned Kronos Quartet, the no less remarkable Vietnamese multi-instrumentalist Vân Ánh Vanessa Võ, and, at times, prerecorded passages (such as a helicopter’s rotor, spoken passages, and musical excerpts).

Librettist Chessman, best known as a novelist (The Beauty of Ordinary Things, 2013, one of whose main characters is a Vietnam veteran), has crafted a tight, resonant tale based on the experience of Hugh Thompson, an army reconnaissance pilot who, with his two crewmen, attempted to stop the massacre by (in Berger’s words) “threaten[ing] to open fire on his own troops.” Chessman, in a movingly worded essay, has reflected on her own involvement in the project — and on her mother’s deep love of the Metropolitan Opera’s Saturday radio broadcasts.

Thompson, in the opera, is dying of cancer and haunted by what he saw that day and by his inability to stop the collective insanity that he and his crew were witnessing. Among the libretto’s most vivid passages is one where Thompson recalls wanting his little boy Bucky, back home, to see this beautiful land that he was flying over, and two others where Thompson hallucinates a radio quiz show, in which a demented emcee grills him about his supposed misdeeds in having his two-man crew challenge the actions of other American soldiers. (They managed to save about a dozen villagers, out of a total of some 500 — the names are all listed in the booklet.)

The musical materials here are immensely diverse. You may have to listen several times to begin to catch the ebb and flow of this startlingly varied work. A prologue includes an excerpt from a Vietnamese lullaby (sung with exquisite little nuances by Pham Thi Mac) and another from “Vietnam Blues” by the short-lived Chicago-based blues singer-songwriter J.B. Lenoir (1929-67). Lenoir’s song includes a protest about the mistreatment of Lenoir’s own people — Black Americans — in Mississippi.

The rest of the work shuttles between events in 1968 and Officer Thompson’s recollections and hallucinations in his hospital bed.

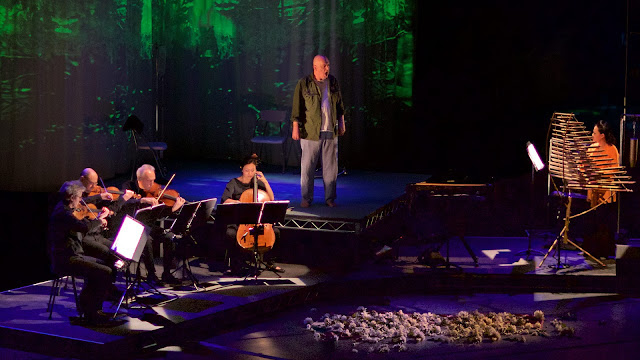

The Kronos Quartet, Rinde Eckert and Vân-Ánh Vanessa Võ perform Mỹ Lai in performance. Photo: Clarity Films

Berger reports that “the musical materials of the work are largely derived from a prayer recited near the conclusion of Yom Kippur, the Jewish Day of Atonement, beseeching pardon before the doors of judgment close.” The chant he chose comes from a recording, made in Israel, of a group of Iraqi Jews led by Yaakov Huri. (You can hear it by clicking at the left-most link near the bottom of this Wikipedia article.) The narrow-range melody (working and varying a descending three-note scalar fragment) is perhaps echoed most noticeably in a passage when Thompson shouts “Open the door” (middle of track 3) and again in an energetic passage for string quartet at the beginning of track 5.

Another chunk of “found material” is the famous Negro spiritual (as the genre used to be called) “My Lord, What a Morning,” widely known through recordings by Marian Anderson and others. The song evokes the Day of Judgment (in the biblical book of Revelation), “when the stars begin to fall” — an apt context for an opera focusing on the choices that humans make in wartime, or perhaps anytime.

The remarkable singer-actor is Rinde Eckert. His keening tenor voice sometimes feels haunted, like that of the great Peter Pears, and very appropriately in this context of pained memory.

The no less astounding Vietnamese multi-instrumentalist Vân Ánh Vanessa Võ plays, at various times, đàn t’rưng (a pitched percussion instrument made of bamboo and analogous to the Western xylophone), đàn bầu (an instrument with a single long string whose note, plucked or bowed, can be sensitively altered in pitch, quickly or very slowly, by means of a vertical handle), đàn tranh (a plucked multi-stringed zither, related to the Chinese guzheng and the Japanese koto), three tubular bells made from spent American artillery shells, and two gongs of different sizes.

Composer Jonathan Berger. Photo: Nicholas Jensen

Like the opening lullaby, Võ’s contributions remind us of some of the vitality of Vietnamese culture and thus of the lives that were snuffed out on March 16, 1968. I was particularly taken with the sound of the đàn bầu, which, in the hands of multi-instrumentalist Võ, can sound like another singing voice. (At one point, I thought I heard the đàn bầu “singing” the opening pitches of another Yom Kippur melody: the “Kol Nidrei.”)

I hesitate to say much more, for fear of spoiling the surprises that this concise and highly imaginative work has to offer. The performers on the recording have brought the work on tour, in a simple but effective staging, using subtle lighting and video (as can be appreciated from this performance video). I hope the work will be taken up by other quartets and with other tenors. Perhaps Võ will be available to participate as well. Or perhaps some other remarkable musician or musicians will master the parts that composer Berger developed in conjunction with Võ for her several instruments.

In the meantime, we have this amazing recording, which is as effective when streamed (I listened to it on my iPhone first) as on a CD played through high-quality earphones or loudspeakers.

The disc is released on the Smithsonian Folkways label, but it is not primarily an instance of folk (or, to use today’s term, “traditional”) music. It is a miniature masterpiece (well, miniature by operatic measurements) from an award-winning composer who, I should have mentioned earlier, teaches at Stanford University, and many of whose other works are available on commercial recordings. Some of them likewise make creative use of — that is, they fragment, distort, etc.—preexisting musical materials, such as the Hebrew song “Eli, Eli” (using a tune that David Zahavi composed for an eloquent, philosophical poem by Hannah Senesh, who was executed by Nazi collaborators in Hungary).

It’s always heartening to encounter a new opera that, like Jeanine Tesori’s Blue, Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones, or Kevin Puts’s The Hours, feels like a keeper. Or, perhaps one would do better to compare Berger’s Mỹ Lai to “chamber-sized” works from the distant or recent past, such as Monteverdi’s Il combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda, Schoenberg’s Pierrot lunaire, Stravinsky’s L’Histoire du soldat, Britten’s several chamber operas and parables, or the recently recorded A Picnic Cantata by Paul Bowles.

I’m happy to recommend Berger’s deeply layered and devastating Mỹ Lai to all listeners, whatever their background or their usual listening preferences. You can see seven minutes of excerpts here. And you can view online The Whistleblower of My Lai, a fascinating hour-long documentary about Hugh Thompson’s brave and principled act that day in 1968. The film also includes revelatory interviews with the librettist, composer, and performers, plus rehearsal scenes giving a vivid sense of how Berger’s deeply involving monodrama came to be and what a profound impact it makes on an audience — or, now, on listeners at home, in one’s car, or anywhere.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). He is on the editorial board of a recently founded and intentionally wide-ranging open-access periodical: Music & Musical Performance: An International Journal. The present review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.

Tagged: Harriet Scott Chessman, Jonathan Berger, Kronos Quartet, Mỹ Lai, Rinde Eckert, Smithsonian Folkways