Film Reviews: “Huesera: The Bone Woman” and “The Starling Girl” — Unorthodox Appeals

By Peter Keough

Both debut features by young women directors open with prayers.

Huesera: The Bone Woman (2022) can be streamed on Amazon and Shudder.

The Starling Girl (2023) screens at the Landmark Kendall Square, the AMC Boston Common, and the Dedham Community Theatre.

Eliza Scanlen in The Starling Girl.

Jem Starling (Eliza Scanlen), the titular 17-year-old heroine of Laurel Parmet’s film The Starling Girl, beseeches God to grant her the grace to perform well as a dancer at a service for her fundamentalist congregation in Kentucky. God does not comply. Instead, she is humiliated and rushes out of the church where she serendipitously encounters Owen Taylor (Lewis Pullman), a 28-year-old elder in the church.

Might he be the answer to her prayer?

Similarly, in Michelle Garza Cervera’s Huesera: The Bone Woman, Valeria (Natalia Solián), a young middle-class Mexico City housewife, joins hundreds of other pilgrims mounting the many steps to worship at a shrine to the Virgin of Guadalupe. She prays that she might conceive a child, but a match cut between the colossal golden statue of the Virgin and a draped figure awash in flames suggests that the auspices are not good.

Both films call out the traditional patriarchal expectations for women, but find opposing them to be a complex and ambiguous undertaking without easy answers. In Parmet’s more conventional film, Jem has submitted wholeheartedly to the will of God — i.e., the men who speak for Him and ensure their own authority — but finds herself still stirred by lustful temptations after she says her prayers at night. The ”worshipful” dance she participates in is an outlet for her more romantic and creative impulses.

When Owen returns with his wife and kids from a long tour as a missionary in Puerto Rico, he also seems to have been touched by some spirit beyond the ken of the Holy Grace Church he serves. After a teenaged boy makes a humiliating confession about his online porn activities to the congregation, Owen tries to soothe the stress of his Bible class by asking them all to lie on the floor and meditate, a technique he learned in his tropical island ministry. Most of the kids think he’s weird. Jem thinks he’s wonderful.

Parmet, who herself had a relationship with an older man as a teenager, does not portray Jem as a victim — at first at any rate. She’s seen as a canny free agent who manipulates circumstances to approach the man she is attracted to. When the dance troupe needs a new leader, she passes by Owen’s house, pretending to have lost her way, and asks for directions. She mentions in passing that she’d like to head the dance troupe and easily convinces Owen, despite his initial, faith-based objections, to make it happen.

Reading up on him in a church bulletin profile, she learns he loves Mexican food and his favorite Bible quotation is I Corinthians 13 (“Though I speak with the tongues of men and angels and have not love” etc.). So she bases the choreography of her group’s upcoming dance on that passage. Later she lets air out of her bike tire, tells Owen she has a flat, and bums a lift from him. During the ride the conversation ranges beyond matters of doctrine to unfulfilled longings and shared passions — such as Mexican food.

According to Parmet, Jem is no victim. Is Owen? In general, the men in The Starling Girl do not impress as members of the patriarchy. At best, like Owen, they seem to have traded their “vanity,” their individual desires and aspirations, for the certainty of fundamentalist faith.

Jem’s father Paul (Jimmi Simpson) is an especially sad case. Once a member of a promising country and western band, he gave it up when he was born again. Now he’s a broken man, an alcoholic tyrannized by Heidi (Wrenn Schmidt), his wife and Jem’s mother, who is perhaps the most strong-willed character in the film. Oddly, Heidi is the only person who suggests that Owen’s position of power might have been instrumental in instigating the relationship.

Like her father, Jem is also born again — more than once in fact. In the course of the film she is immersed on several occasions in various bodies of water, each a significant baptism. Though frustratingly self-destructive, she perseveres, refusing to be defined by the rules of her church or the rules of this genre. If, like her, you can survive the dollops of treacly Christian music throughout the film, you will receive your reward at the end with the purifying strains of Emmylou Harris singing “Tennessee Rose.”

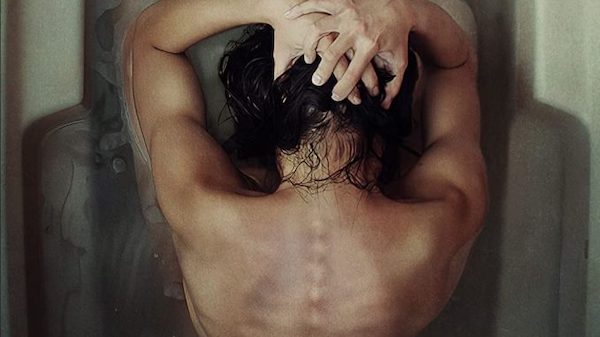

A scene from Huesera: The Bone Woman.

In Mexico City, meanwhile, Valeria does not face the same oppressive, patriarchal restrictions as Jem. Her husband Raúl (Alfonso Dosal) is kind, thoughtful, and permits her independence. He helps with the housework and encourages her in her carpentry hobby. That activity must end, however, because the visit to the shrine apparently worked. Valeria must forego the chemicals and sharp tools of her trade during her pregnancy — though not before she finishes a crib for the new arrival.

Valeria was not always so placid, docile, and bourgeois. A chance encounter with Octavia (Mayra Batalla), an old flame, inspires flashbacks to her youthful days in the punk scene, including an occasion when, on a dare, she submerges herself under water while her friends count out the time. This baptism by way of waterboarding did not seem to take hold. Somewhere along the line — perhaps under pressure from her oppressive, disapproving family — Valeria gave rebellion up for the standard comforts of a middle class family life.

Valeria’s pregnancy gets off to a rocky start. She can’t eat and she keeps seeing the apparition of a crawling woman with compound fractures. The figure terrifies her and provokes her into erratic behavior. During one manifestation, while she is babysitting for her bratty niece and nephew, she injures them in the course of supposedly protecting them from the specter. No one believes her story; instead, her behavior confirms the disgust of her family and makes her husband doubt her sanity. The birth of the baby only exacerbates the domestic turmoil, culminating when she dozes off while the baby cries, wakes up, and realizes the kid is gone and she doesn’t know what happened.

As a last resort she seeks help from her Aunt Isabel (Mercedes Hernández), the only sympathetic member of her family. She had accompanied Valeria to the shrine at the beginning of the film and is involved in a coven of sorts that combines the rites and icons of the traditional Catholic Church with magical, darker arts. These women are sinister, though they are not as depraved as the diabolical crew in Rosemary’s Baby (1968). Still, the rituals they perform evoke striking body horror imagery. They offer an exorcism of sorts, but of what? Though murky and ambiguous, Cervera’s film affirms a woman’s right to choose.

Peter Keough writes about film and other topics and has contributed to numerous publications. He had been the film editor of the Boston Phoenix from 1989 to its demise in 2013 and has edited three books on film, most recently For Kids of All Ages: The National Society of Film Critics on Children’s Movies (Rowman & Littlefield, 2019).

Tagged: Eliza Scanlen, Huesera:The Bone Woman, Laurel Parmet, Michelle Garza Cervera