Film Series Review: “Late Kiarostami” — Spotlighting the Works of a Master Iranian Filmmaker

By Betsy Sherman

This not-quite-full retrospective contains three masterpieces of Iranian cinema: Close-Up, Taste of Cherry and The Wind Will Carry Us.

Late Kiarostami – A film series at Harvard Film Archive, Cambridge, through May 27.

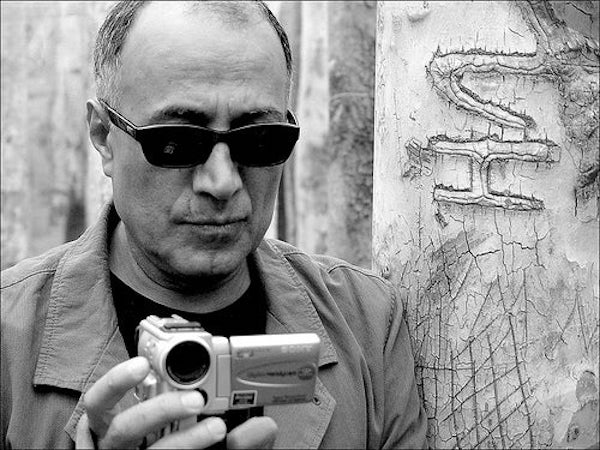

Legendary Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami. Photo: Verso

The Harvard Film Archive follows up its 2022 series Early Kiarostami, spotlighting the Iranian director Abbas Kiarostami (1940-2016), with, ta-da: Late Kiarostami. In this half of the not-quite-full retrospective, audiences can see how he built upon what he learned from his many years making sophisticated films about and (not only) for children.

The filmmaker died in Paris on July 4, 2016, at the age of 76 of gastrointestinal cancer. This series contains three masterpieces of Iranian cinema: Close-Up, Taste of Cherry and The Wind Will Carry Us.

The director’s disarming 1990 Close-Up (playing Sunday, May 21, at 7 p.m., on 35mm film) was made before And Life Goes On and Through the Olive Trees, both shown in the ’22 series. Close-Up marked a breakaway from convention with its blurring of the line between documentary and fiction. It wasn’t the first film to do so, but it’s been one of the most influential.

In a fragmentary way, it relates a real-life incident that fascinated Iran. Kiarostami read about the arrest of Hossein Sabzian, an unemployed bookbinder who impersonated the well-known Iranian film director Mohsen Makhmalbaf and told a middle-class family he’d put them in a movie, if they provided financing. Kiarostami visited the man in prison, where he was awaiting trial, and received permission from the court to film the proceedings. He found it wasn’t hard to convince everyone involved, even the judge, to restage events in this saga — they all wanted to be on the big screen. There’s a cameo by Makhmalbaf at the end of the film.

The situation jibed with Kiarostami’s core belief about cinema, that it uses lies to get to the truth. His Sabzian is not a conman in the usual sense; he’s an impassioned cinephile who saw the mistaken identity as a sign that he too could participate in the movies. Close-Up is about identity and simulation. The filmmaker shot the recreations of Sabzian’s interactions with the Ahankhah family on 35mm film and the courtroom scenes on 16mm, so the latter would feel more like news footage.

Kiarostami had been moving toward loosening his screenplays and incorporating happy accidents, often withholding information in order to mess with audience expectations. In Close-Up, this style plays out pretty quickly into the film. Police officers and a reporter travel in a cab to the Ahankhahs’ house, where Sabzian will be arrested (the location is really their house). We want to follow them in, but the camera stays with the waiting driver, who picks some flowers and kicks an aerosol can. The camera follows the can rolling down the road. The shot is at first baffling, then hilarious, then feels inspired. Kiarostami isn’t depriving the audience of anything here; instead, he’s presenting a wider canvas on which “cinema” can function. Werner Herzog, who has made some iconoclastic documentaries himself, called Close-Up “the greatest documentary on filmmaking” he had ever seen.

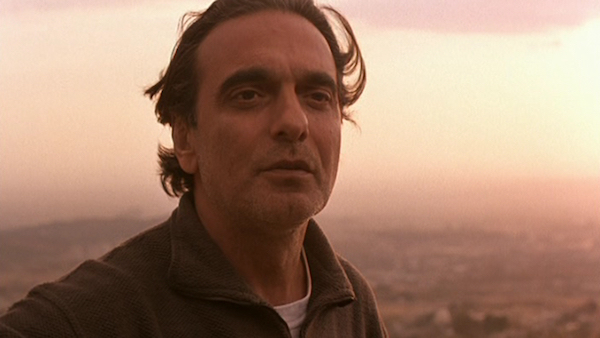

Homayoun Ershadi in a scene from 1997’s Taste of Cherry.

A Palme d’Or winner at Cannes, the 1997 Taste of Cherry (Friday, May 19, at 7 p.m., and Friday, May 26, at 9 p.m., on 35mm film) concerns the dilemma of Mr. Badii, whose intentions aren’t clear at the outset. The 50-ish man seems well educated and middle class. He’s seen driving his Range Rover around the outskirts of Tehran, looking for lone men. His proposition isn’t one you’d guess. He intends to commit suicide in a grave he’s already dug in a remote area. What he wants is to hire someone to go to the grave early the next morning and shovel dirt on him (the cash payment will be there, with Badii’s body).

There’s little personal information supplied about Badii, or a reason given why he wants to die. Three scenes depict conversations with unsuspecting men who take a ride in Mr. Badii’s car: a Kurdish farm-boy soldier, an Afghan seminarian, and a Turkish taxidermist. As always, it’s how the story is told that counts. Kiarostami sets a mood of alienation, using signature images such as the occasional lonely tree on a hill and rubble (in earlier movies caused by an earthquake, here it’s construction sites).

Kiarostami continues his practice of casting nonprofessionals. Homayoun Ershadi, who plays Badii, wasn’t an actor, he was an architect; the director happened to see him waiting at a traffic light and felt his face was perfect for the phlegmatic Badii. Ershadi’s own Range Rover co-stars with him. However, Ershadi wasn’t the man speaking in the car with the three passengers, although the film is edited to look as if he is. Kiarostami himself was in the driver’s seat with them, using a hidden camera he operated by pushing buttons. The seminarian thought he was really about to commit suicide; in the film, he cites passages from the Koran to dissuade him. The cabdriver who played the taxidermist, who urges Badii to savor life’s simple pleasures such as the taste of cherries, wasn’t cast until three days before the end of the shoot. A further example of Kiarostami’s hands-on approach is that he and his son Bahman were the ones who dug the grave.

A scene from 1999’s The Wind Will Carry Us.

The 1999 The Wind Will Carry Us (Friday, May 12, at 7 p.m. on DCP, and Sunday, May 21, at 3 p.m., on 35mm film) won the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival. It shares several characteristics with Taste of Cherry. Physically, it takes place outdoors (450 miles from Tehran, in Kurdistan) and places someone in a deep hole in the ground. Socially, it takes a critical look at middle-class city folks’ condescension toward less-educated rural people. Stylistically, it incorporates absences, such as certain characters that are heard but kept off-screen.

The story centers on Behzad (Behzad Dorani), a media professional, who arrives with a crew (that we never see) in a remote Kurdish village for a reason not explicitly stated. It seems their task is to record a funeral rite practiced by women in that area; however, a 100-year-old dying woman apparently isn’t going to die on their schedule. So Behzad bides his time. One comical motif that illustrates technology’s grip on him is that whenever he needs to use his cellphone, he races in his car to the top of a mountain where he might get a signal.

Kiarostami plays with Behzad’s surroundings, visual and aural, to shake the character (and the viewer) into a heightened awareness. The film’s title is from a poem by Forugh Farrokhzad. Behzad recites it as part of his flirtation with a 16-year-old girl who milks a cow in a dark cellar (we see her from behind). The visitor may have a selfish motive, but the poem is profound and ties in with the presence of death that pervades the film. Kiarostami chose it because it expresses the transitory nature of life. The Wind Will Carry Us recalls the spiritual cinema of Andrei Tarkovsky and Robert Bresson.

In June of 2000, Kiarostami visited the HFA to screen The Wind Will Carry Us. During that same time, an exhibition of his landscape photography was on view at a Manhattan gallery (it was well worth the trip!).

Next in Kiarostami’s filmography is the 2002 Ten, a departure in that it centers on a woman (she participates in 10 conversations with passengers she drives in her car) and that it was shot on digital video. However, the HFA has chosen not to show it, or its film-essay follow-up 10 on Ten, in light of recent allegations by star Mania Akbari that Kiarostami plagiarized her work, incorporating footage shot by her into Ten without her permission and without crediting her. She also accused him of abuse.

To discuss Iranian cinema of the past 40 years one must also discuss the apparatus that surrounds it — those “morality police” we’ve been hearing so much about. Art and entertainment must not disrespect Islamic values, as they are interpreted by the theocracy. Iranian film scholar Mehrnaz Saeedo-Vafa has noted that “Many ellipses in Kiarostami’s work grow directly out of this process” of evading strictures.

Although Iran’s president has less power than the Islamic Republic’s Supreme Leader, the holder of the office does make a difference. Under the administration of Mohammad Khatami, from 1997 to 2005, there was some relaxation in oversight by the censors. His successor, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, was a hard-liner; consequently, enforcement was ramped up again.

In reaction to this, Kiarostami became more of a player on the international stage. He directed a section of the 2005 feature Tickets (not in the series), as did Ken Loach and Ermanno Olmi. In 2008, he directed his first opera, Mozart’s Cosi fan tutte, at a festival in Aix-en-Provence, France. French actress Juliette Binoche had long wanted to collaborate on a project with the director. They began shooting a feature in Tuscany just as Iran’s controversial 2009 presidential election took place and was followed by the violent suppression of Green Movement protests. At that time, Kiarostami told Le Monde that he wanted to make films in his country, but “the political situation is such that even the possibility of working [in Iran] seems very compromised. And I don’t know, frankly, if that will be possible in the future.” He said that his films hadn’t been shown in Iran for 12 years.

William Shimell and Juliette Binoche in a scene from 2020’s Certified Copy. Photo: IFC films

The film with Binoche was the 2010 Certified Copy (Copie conforme) (Saturday, May 27 at 7 p.m.). It was Kiarostami’s first feature made outside of Iran, in languages (English, French, and Italian) not including Farsi, and with a movie star. With the feel of a European art house film, it combines an intellectual debate on the philosophical value of copies in relation to original works with the depiction of a crumbling relationship, incorporating a panoply of Italian art, architecture, and natural splendors.

William Shimell, a British opera singer who performed in Cosi fan tutte, plays James, an art historian in Italy for a lecture on his book that shares the movie’s title. Binoche is a never-named character (identified in the credits by the pronoun “Elle”) who attends the event and leaves a note inviting him to visit her antique shop (she has a teenage son who mocks her interest in the author). He does, the next day, and they take a road trip to Lucignano, an hour outside Florence. Known as a destination for weddings, the place seems overrun by brides and grooms, to the bemusement of a skeptical James.

Almost halfway into the film, the pair eat at a restaurant where, when James steps away from the table, a woman speaks to Elle, assuming that they’re a married couple. James returns and the conversation, which has been somewhat prickly, continues. In the time it takes for a tear to travel down Elle’s cheek, something shifts, and now the two are a couple who have been married for 15 years.

This outward copy — with no costume changes — of the just-met pair requires some recalibration on the part of the viewer, but it’s not hard to get drawn into the melodrama. Like Roberto Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy (which starred the director’s wife Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders) and Kiarostami’s own 1977 The Report (based on his marriage, which ended in divorce), Certified Copy explores relations between a cold, distracted man and a frustrated woman who tries to rekindle the flame. Reflections and mirror-images abound in the visual scheme. “La Binoche” brings an authenticity of emotion to her performance, proving again that she’s one of the very best actresses working in film.

The rest of the series is as follows:

A scene from 2001’s ABC Africa.

ABC Africa (2001) (Friday, May 19, at 9 p.m.) presents life and death in another context, that of AIDS in Uganda. The documentary was made at the request of Uganda Women’s Efforts to Save Orphans, a program of the UN’s International Fund of Agricultural Development. The agency reported that 1.6 million children and teenagers had lost one or more parents to AIDS and civil unrest. The portrait of these young people is also self-reflexive, with Kiarostami and his assistant discussing their role as outsiders in a poor, troubled country. Jonathan Rosenbaum called the film “as much a celebration of the children’s inner resources as it is an exposure of their plight.”

Five Dedicated to Ozu (2003) (Monday, May 15, at 7 p.m.) has no dialogue or characters in its five sections, just the offerings of nature in sight and sound. Four parts were shot along the banks of the Caspian Sea, and one at a pond (an outstanding frog chorus here). It’s a tribute to the feelings evoked by the films of Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu — to whom the HFA is dedicating its summer schedule, with a complete retrospective.

A scene from 2008’s Shirin.

Shirin (2008) (Saturday, May 20, at 7 p.m.) is an unusual and surprisingly stirring movie experience. After having shot several productions in the countryside, Kiarostami sets this nonfiction film in the darkness of a Tehran movie theater. The light of the projector travels to the screen and bounces back at the faces of an audience that contains 108 hijab-wearing Iranian actresses (plus Juliette Binoche). The camera is pointed at the people watching a movie we hear but never see directly. It’s an adaptation of Khosrow and Shirin, a work by 12th-century Persian poet Nezami Ganjavi that’s as well-known in Iran as Romeo and Juliet in the West. The actresses have been cast to play themselves, absorbing and reacting to the tale, with its imagery appearing to us via their eyes. It’s a potent statement protesting the invisibility of women in Iran.

Like Someone in Love (2012) (Friday, May 26, at 7 p.m.) was co-directed by Banafsheh Violet Modaressi. Kiarostami felt a kinship with Japanese culture and wanted to explore the role of tradition in the modern world (a major theme in Ozu’s works). The feature he shot there, in Japanese, is wry and mysterious, with the catalyst figure a young college student/sex worker. Her encounter with a client — a lonely elderly scholar — is a meeting of mind, body, and soul. Themes of deception common in Kiarostami’s work are given a lighter touch here.

24 Frames (2017) was released posthumously. This final work of a master bursts with creativity, but through means that may seem incongruous: computer-generated effects. The subjects include animals, plants, and landscapes. As in Five, there’s no dialogue, just music and sound effects. The first of its four-and-a-half-minute vignettes animates Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting Hunters in the Snow. From then on, Kiarostami “extends” his own still photographs, imagining what happened before and after the click. These tableaux are a reminder that the filmmaker was also a poet and painter — and, circling back to Early Kiarostami, a maker of artistic educational shorts. Arts Fuse review

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for the Boston Globe, Boston Phoenix, and Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Tagged: Abbas Kiarostami, Close Up, Early Kiarostami, Taste of Cherry