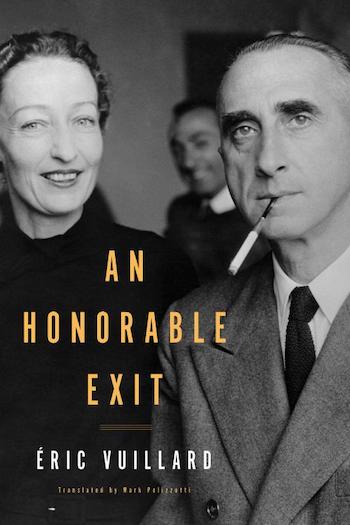

Book Review: Éric Vuillard’s “An Honorable Exit” — A Brilliant Chronicle of a Tragedy Foretold

By Thomas Filbin

Éric Vuillard’s method is to create an ironic rapport with the powerful: his vignettes dramatize how France’s elite delude themselves into thinking the colonial world order can be kept intact after World War Two.

An Honorable Exit by Éric Vuillard. Translated from the French by Mark Polizzotti. Other Press, 160 pages.

If you have been deeply curious how the United States became involved in Vietnam, read Éric Vuillard’s book about the end of the French colonization of that country and the final days of its war against the Viet Minh. Our own engagement in that faraway land, which cost so many American lives and unknown hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese, was the mirror of a disaster that took place decades earlier: the Vietnamese war of insurgency against the French followed by that country’s abandonment of Indochina. France’s forced exit — propelled by a nationalist uprising — should have been a lesson, but America, steeped in the domino theory (if one country fell to communism, its neighbors would soon follow) blindly followed the failed steps taken by France. There wasn’t a moment’s reflection that the two situations were very much alike. It ended for the United States in 1975, just as badly as it did for the French in 1954. Was it the blindness of pride or breathtaking stupidity that led America down such a faulty path? The madness of repeating the same action and expecting a different result victimizes nations as well as individuals. Vuillard’s short but brilliant dissection of the French disaster, its final chapter touching on American hubris, draws on anecdotes and historical scenes to dramatize a chronicle of a tragedy foretold.

If you have been deeply curious how the United States became involved in Vietnam, read Éric Vuillard’s book about the end of the French colonization of that country and the final days of its war against the Viet Minh. Our own engagement in that faraway land, which cost so many American lives and unknown hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese, was the mirror of a disaster that took place decades earlier: the Vietnamese war of insurgency against the French followed by that country’s abandonment of Indochina. France’s forced exit — propelled by a nationalist uprising — should have been a lesson, but America, steeped in the domino theory (if one country fell to communism, its neighbors would soon follow) blindly followed the failed steps taken by France. There wasn’t a moment’s reflection that the two situations were very much alike. It ended for the United States in 1975, just as badly as it did for the French in 1954. Was it the blindness of pride or breathtaking stupidity that led America down such a faulty path? The madness of repeating the same action and expecting a different result victimizes nations as well as individuals. Vuillard’s short but brilliant dissection of the French disaster, its final chapter touching on American hubris, draws on anecdotes and historical scenes to dramatize a chronicle of a tragedy foretold.

Vuillard details in crisp narrative episodes why the French resisted Ho Chi Minh’s nationalist revolution. Arrogance was one driver, but it was also because the country had considerable commercial and financial interests in a land that was rich in natural resources. And it had a large labor force to be exploited. Timber, rubber, sugar, and minerals were plentiful and the Banque de L’Indochine, a French creation, kept the wheels of commerce and money moving. One of Vuillard’s chapters details the incestuously interlocking boards of the top corporations. Cousins and in-laws, most with connections to government ministries, ensured that French policy in Vietnam would support the interests of the ownership class. (What is good for General Motors is not just good for America — it is a winning strategy for the elite in all the developed countries.) The posh 8th and 16th arrondissements de Paris were a beehive of power, money, and political influence which kept the colonial superstructure intact. At least the French got paid for their imperialist occupation of Vietnam through riches that yielded great profits for the nation’s business upper crust. America ended up with nothing but a futile war and domestic upheaval. It might be argued that French corporations were there for their private enrichment — underwritten and policed by the French government and military. America’s stake was ephemeral at best. The French colonial regime dated from the 1880s. The country initially justified its occupation under the familiar formula of “white man’s burden” — bringing civilization to the unenlightened. But French companies became addicted to the control of so much cheap labor — profiting from modern slavery. The reason the French remained until they could stay no longer was that it had established such a lucrative system of servitude.

In a series of chapters, a succession of historical re-enactments, Vuillard underlines the intransigence of the French, buoyed by the belief they were entitled to rule Vietnam. They stubbornly refused to recognize any potential for the country’s self-determination. The French commander, General Henri Navarre, came from a wealthy family and was “…learned, caustic, self-assured, and cold…” according to Vuillard. Trained as a cavalry officer, he was decorated in World War One, and served in Algeria before taking command of French forces in Indochina in May of 1953. Unable to grasp the will and resourcefulness of an indigenous army that could move material by bicycle, he could not envision the possibility of defeat. Ironically, America in the early ’50s recognized the deficits of the French military. Pulitzer prize-winning author Ted Morgan, who is now in his nineties and served in the French army in Algeria, maintains in his book The Valley of Death that Eisenhower privately disparaged the French military and considered war in a country like Vietnam to be unwinnable.

After the Second World War, Ho Chi Minh’s war of insurgency grew more successful and the costs of reinforcing the empire became obvious and expensive. “A billion a day?” a member of the National Assembly asked when told of the expense of the French occupation in the face of the Viet Minh led by Ho Chi Minh. The rebels were undaunted by their own casualties as they inflicted a surprising amount of damage on the French. Ho was once said to have predicted, “We will lose a hundred men for every one of yours, but in the end you will tire of it first.” The funding the war demanded crippled the French economy, but strident nationalistic voices maintained that the country had a historical obligation to remain. Vuillard, in an observant side chapter, shows that the French companies were so heavily invested in Vietnam that withdrawal would have devastated them. Either the country stayed or left, financial disaster was sure to follow. Better that all should suffer than end an occupation that was profitable for the empire. Whenever someone says it is not about the money, it is about the money.

Defeat after defeat drove the French to a fatal decision to encamp themselves in a stronghold at Dien Bien Phu. At that point, the end was plainly in sight. The French made a strategic error to dig in there, building more and more shelters, trenches, and a below ground command post. “Ten thousand men already lived there…and every day they delivered tanks, jeeps, trucks, an advanced surgical unit, copies of Playboy, and dumpster loads of canned food,” Vuillard writes. By choosing a fixed position the French invited being encircled and then overrun. And that is what occurred.

The Prime Minister, Pierre Mendes France, put career at risk by courageously standing in Parliament declaring that there was a “solution…to reach a political accord, that is with the people we are fighting.” These words were shocking and heretical. Yet once spoken it was plain to every realist in the government that permission had been given to reverse course. Victory was an illusion. France negotiated a peace that created North and South Vietnam and withdrew its forces. The war would continue, of course, but with the United States stepping in to defend the South Vietnamese government in yet another protracted conflict with considerable casualties and a tragic outcome. France lost 91,000 trying to maintain its colony and the United States, refusing to accept France’s lesson, lost 55,000.

There were holdouts to French withdrawal, one of them Maurice Violette, predicting that Algeria and Tunisia would follow the path of Vietnam. Of course he was right in some fashion, but Vietnam was symptomatic of a larger political change the colonial period was in its death throes. American Secretary of State John Foster Dulles — who was rabidly paranoid about communism — is alleged to have offered the French two atomic bombs to use on the Vietnamese. Meddling in world order was very much of interest to Dulles and his brother Allen, head of the CIA. In 1953, they were part of an action to overthrow the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh in favor of strengthening the monarchical rule of the shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Presumably, the idea was that democracy had to be destroyed in order to keep the world safe from the red menace.

Vuillard’s method generates a kind of ironic rapport with the powerful: his vignettes dramatize how the higher ups delude themselves into thinking the colonial world order can be kept intact after World War Two. Readers are dipped into the mentality of the privileged: reigning supreme over the underclass was inviting and rewarding for French leaders. An Honorable Exit not only illuminates the machinations behind the Vietnam debacle for the French, but shows just how damaging an anachronistic hunger for domination can be. It is bad enough that America blundered into a war, but worse still that its defeat was clear from the start. The glaring example of French failure was a sign of the times.

Thomas Filbin is a free-lance book critic whose work has appeared in The New York Times Book Review, The Boston Sunday Globe, and The Hudson Review.

Tagged: An Honorable Exit, Éric Vuillard, Mark Polizzotti, Other Press

Vuillard is simply the best french writers of.his génération, and of today.