Music Interview: Singer/Songwriter Peter Case Talks About His New England Connections and “Doctor Moan”

By Blake Maddux

“I go out on the road and the clubs are full everywhere I go,” Peter Case gratefully acknowledges. “People come out to hear me play. It’s an amazing gift to have that.”

As a band member, Peter Case is known for his work in The Nerves, who in 1976 recorded “Hanging On the Telephone.” That song soon secured new wave classic status thanks to Blondie, and The Plimsouls, whose 1983 song “A Million Miles Away” — along with three of their other ones — was featured on the killer soundtrack to the 1983 cult favorite Valley Girl and has since become a power pop standard.

(Movie clip featuring Nicolas Cage here)

As a solo artist, the Buffalo native’s credits include an eponymous debut that Robert Palmer of the New York Times put at the top of his best albums of 1986 list and two that received Grammy nominations for Best Traditional Folk Album: Avalon Blues: A Tribute to Mississippi John Hurt (2001) and Let Us Now Praise Sleepy John (2007).

His renown, while limited, is sufficient to have earned him official induction into The Buffalo Music Hall of Fame — “I’m looking at my statue right now. It’s up on the mantelpiece,” he told me in a recent phone interview from his home in San Francisco — and unofficial membership in what he calls “The Anonymous Hall of Fame.”

Still, Case is thankful for the fans that have kept him afloat for nearly half a century.

“I go out on the road and the clubs are full everywhere I go,” he gratefully acknowledges. “People come out to hear me play. It’s an amazing gift to have that.”

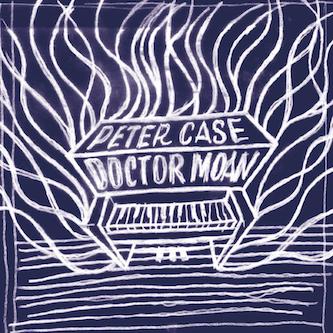

On April 16, some of those fans will gather at Boston Harbor Distillery to hear him showcase his latest album, the March 31 release Doctor Moan. (Details and tickets available here.)

The Arts Fuse: Do you have any connections to Boston in your personal or professional life that are particularly meaningful to you?

Peter Case: My father’s family came from Boston. My grandfather, Lewis Case, was a train conductor out of Boston. My dad was old when I was born — I was the last kid — and he saw Babe Ruth play for the Red Sox!

Then in my early teens, I hitchhiked up to Boston in the winter of ’71 and saw Lightnin’ Hopkins perform at a theater in Cambridge. That was very exciting. It was electrifying and really inspirational.

In ’77, The Nerves performed at The Rat for several nights with DMZ. We were probably one of the first bands to do a tour without a record company. We had an EP out on our own label. The guys from The Cars came to the gig. They were just getting together. That was fun playing up there. We stayed at this guy Oedipus’s house.

I have a lot of friends up there. “Yukon” Bob Stubblebine — he runs Stubblebine Lutherie — is a good friend of mine. He does house concerts with me sometimes and is from my hometown. Chris Smither is a good friend. The late Al Perry was a good friend, too.

AF: You were originally scheduled to return to Atwood’s Tavern before it announced that it was closing at the end of March. What do you remember about playing there in the past?

PC: I loved playing there, man. It was a great atmosphere and the crowds were great. It was really intimate. It was one of the stops I looked forward to on tour. The Atwood’s people were the best.

AF: You were the subject of a 1973 documentary called Night Shift and you figured prominently in 2011’s Troubadour Blues. Now there is one called Peter Case: A Million Miles Away.

PC: This new one is really well done and people really like it. [Director] Fred Parnes is an excellent storyteller, so you don’t even really need to know who I am before you see the movie. It got rated as one of the best things that Rolling Stone saw at the Americana Conference. They loved it and a lot of people are giving it a good review. It should be dropping at the end of May on a streaming platform, but I’m not sure which.

AF: You said in a recent interview that you recorded 2021’s The Midnight Broadcast “in a church up in New England.” Tell me more about that.

PC: We recorded it in this place called the Old Whaling Church in Martha’s Vineyard. It had an incredible reverberation and an all-natural echo. They have a nice piano in there and we cut this whole album in a few days. It goes from folk music — it’s got the first song I ever wrote on it — and then it’s got rock songs and ambient music on it. We recorded the whole thing on a Nagra, and we were using Moog on some of it. So it’s between a folk record and a record with Eno-esque kind of qualities. I’m really proud of that one, but nobody heard it because it came out during the pandemic.

The Midnight Broadcast was inspired by a car trip in the middle of the night across Massachusetts. I had a Boston gig and I had to drive at night somewhere for something the next day. I was on some of those Massachusetts back road kind of highways. And I got this radio show that came in that was just playing incredible music. It was kinda going in and out of focus, and it just slayed me. Some of the songs I’d never heard, some of them I had, but they really hit me in the car. And what I wanted to do was make a record that kind of caught that experience.

AF: Do you feel pretty good about how Doctor Moan turned out?

PC: Yeah, I feel pretty good about it. I was happy that I was able to focus on it without having to go on the road. I got to write it, learn how to play it, and then record it all in one shot without having to interrupt my thought process. It was during the pandemic, so I just stayed focused on it. I am real proud of this record. It’s getting a great reception, too.

AF: What has your relationship with the piano been throughout your life and why did you decide to bring it to the fore on this album?

PC: The first song I ever wrote was on the piano. I used to play piano back in Buffalo with bands like Skull Street Train. I also played piano for the Saint John [William] Coltrane African Orthodox Church up here in San Francisco for a few years before the pandemic. It was just sort of a fluke that I ended up playing with them, but it was an amazing learning curve. I basically play rhythm piano. I’m not a big soloist like McCoy Tyner or somebody like that.

So I go way back with the piano, and this was my opportunity to really put it forward. I’m here in a room in the front of my place with a Baldwin Spinet that somebody gave me. I just said, “I’m locked in this room, I’m gonna be here for a while. I’m just gonna play this piano.” I played it every day, and then the songs started to pop out.

AF: Was “4D” always meant to be an instrumental or did you consider writing words for it?

PC: I did add words to it, but I enjoy just playing it as an instrumental. There are words to it. It seemed like the record was getting claustrophobic, and I thought it just needed that breather. There are a lot of words in that last song and it tells a whole story. One more story was going to be too much.

Singer-songwriter Peter Case. Photo: Ekevara Kitpowsong/ The Aperturist

AF: I’d like to wrap up by going back to The Nerves and The Plimsouls. Did you have any sense of the potential timelessness of “Hanging on the Telephone” or “A Million Miles Away” when you first recorded them?

PC: When I first heard “Hanging on the Telephone,” I thought it was a great song. All great songs are timeless if you ask me. Buddy Holly’s stuff is timeless, but so is “Hanging on the Telephone” or “When You Find Out” by The Nerves.

AF: Do you ever think to yourself, “If those songs could become so well known, why not this one or that one?”

PC: A lot of it is luck. I don’t think “Hanging on the Telephone” or “A Million Miles Away” are the best things I’ve been involved with necessarily. But “A Million Miles Away” really got promoted and caught sort of a vibe in the culture. It’s a combination of elements.

We thought The Nerves were gonna be huge, and we could hardly get much going. And then Blondie does it and sells seven or eight million copies of our song. It was mind-boggling.

I had this song that I sang on the Letterman show called “Dream About You.” That started to be sort of a radio hit, but then the record company were the people who had Nirvana, so they just kinda moved off of my record.

But these things happen. It doesn’t matter, though. That’s not really what I’m here for. I’m just trying to stay musical, stay creative, stay in the flow of creativity. When things happen, they do. I didn’t set out to get a guy to make a movie or anything. Things just happen.

This record’s getting a great reception and the last one nobody even knew it was out. You can’t really control it, so you just try to keep making the best music you can. I always try to make something that I would love. Your job as a musician, in a way, is to come up with your dream of what music should be. So that’s what I do.

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who regularly contributes to the Arts Fuse, the Somerville Times, and the Beverly Citizen. He has also written for DigBoston, the ARTery, Lynn Happens, the Providence Journal, The Onion’s A.V. Club, and the Columbus Dispatch. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife and five-year-old twins — Elliot Samuel and Xander Jackson — in Salem, MA.