Visual Arts Review: Minimalism — An Incomplete Project

By Helen Miller and Michael Strand

Donald Judd, Untitled (Black), 1991. Extruded aluminum, anodized in Black, Edition of 12, 5 7/8 x 41 3/8 x 5 7/8 inches. Photo courtesy of Krakow Witkin Gallery

The defining feature of Lines and Planes and Space at Krakow Witkin Gallery (through April 22) is Donald Judd’s Untitled (Black) (1991), both in terms of the artwork itself and the independent thinking behind it. One of twelve anodized black aluminum wall pieces from a series made in twelve different colors, the work simultaneously absorbs light like rubber and reflects the ceiling-mounted LEDs like moonlight glittering on a lake. Ryan Cross, the gallery’s director, explains that such effects are created by fine lines etched into the impressionable metal during the extrusion process, which is not to say that they are unintentional. Following the famously particular artist’s strict instructions, the piece is hung slightly below eye level. On first impression, it appears to hold dominion over the gallery’s New England-adobe open plan. But is Judd the law in this town? The prints in the show, made in the span of ten years between 1963 and 1973, are more elusive. What, we are led to wonder, is the project of minimalism today?

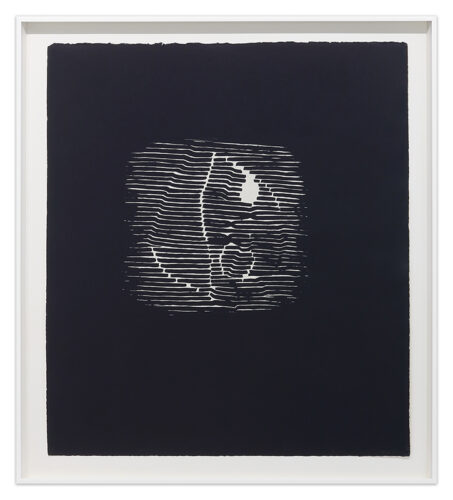

Gertrud Goldschmidt (Gego), Untitled, 1963. Lithograph, Edition of 20, 18 x 15 inches. Photo courtesy of Krakow Witkin Gallery

Untitled (1963), a lithograph by Gertrud Goldschmidt (Gego), a German-born Venezuelan artist whose retrospective just opened at the Guggenheim last week, hangs on the adjacent wall. This work on paper is equally precise and visionary, yet the encompassing use of black in Gego’s print is more playful, less stern. Where Judd’s lines never leave the xy-axis, Gego’s marker-esque marks hiccup or hit a speed bump just when you think you’re onto them. At the center of the image, a circle seems always about to resolve in white or bent black lines. The highlights, which themselves hover at the edge of recognition, could be leaks of paper untouched by the printer’s ink. This version of minimalism is less impenetrable: we can enter between the lines, which are for their part free to move around our interest. The seemingly infinite play of figure and ground and in particular the conjuring of space out of ink on paper prefigures the artist’s kinetic sculptures — “drawings without paper” or “drawings in space.”

Ad Reinhardt’s Untitled (1) (1966), Untitled (9) (1966) and Untitled (10) (1966) are some of the New York School painter’s few screenprints and feature the same T-shape motif common in his large-scale work. Vertically and horizontally extended blocks are only slightly different shades of blue or black than the background, and resemble the passages of color that appear when you close your eyes. Across the room, a similarly unexpected depth — a sense of seeing into space — occurs in Sol Lewitt’s Straight, Not-Straight and Broken Lines in All Horizontal Combinations (Three Kinds of Lines & All Their Combinations) (1973). The impression is of lines running along wavy parallel tracks, which give the illusion of motion and mountainous space. However literal, the work is also light-hearted, expansive, and experiential. The continuum of foreground and background in Lewitt’s seven prints gently slopes, inviting us to scan upward and across the spread.

Segmentation also disrupts the visual field. Untitled (1973), Brice Marden’s etching on Rives BFK paper, recalls Rothko, not least because of its location at the far end of the tapering main room of the gallery, which can feel chapel-esque. Yet Marden, given the stochastic additions of his own painterly approach to printmaking, emphasizes picture plane rather than religion or spirituality. The inky borders left by the etching plate set off three distinct levels — white, black, and splotchy-ink. The imperfect alignment of the stack — the gaps and overlaps where the impressions meet — emphasize disruption and distinction rather than cohesion. The consequent illusion of actual panels is further achieved through the degree to which the paper, dampened during the printing process, now warps. Ultimately, the separation is not only material but perceptual; the smooth black “waist” of the work recedes while the rough white top and bottom pop.

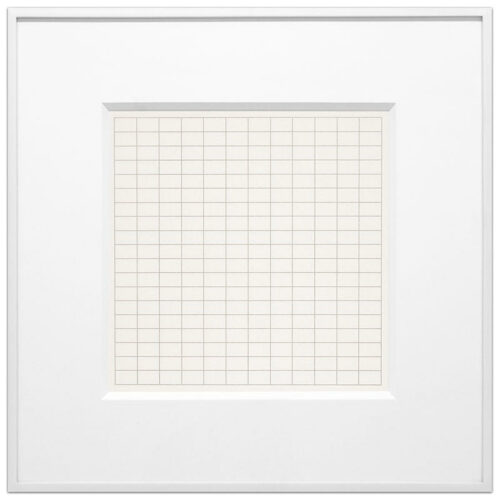

Agnes Martin, On a Clear Day #05, 1973. Screenprint on Japanese Mulberry paper, Edition of 50, 12 x 12 inches. Photo courtesy of Krakow Witkin Gallery

On a Clear Day #05 (1973) is a small screenprint from self-proclaimed abstract expressionist Agnes Martin’s only foray into the medium, which occurred after a significant period of no artmaking at all and lasted nearly two years. On Japanese mulberry paper, a brownish gray grid is softer in appearance than the black we might expect of the no-nonsense form. The shapes inside the square similarly defy expectation: They are rectangles and not, as we had first imagined or assumed (on account of their square frame), perfect squares. The rectangles are in the form of a grid as opposed to the staggered, alternating layout of a brick wall in which we are accustomed to seeing rows of rectangles. These differences from what we had anticipated move us — not unlike the differences in shape and color in the Reinhardt — and separate us from our initial impressions. This is a singular yet shifty instance of Martin’s printmaking. An “abstract emotion,” in Martin’s words, like moments of quiet happiness or a peaceful calm, may arise in the face of such clear-eyed experimentation.

We wonder at the mirage in Gego’s lithograph, the immiscibility of oil and water echoed in the ground’s resistance to the near-flood of black ink, in lighted ripples. Reinhardt’s rectangles also make us question our senses, and engage us conceptually, taking what appear to be pure voids and showing us how they only appear that way because of the push-pull effect of their relative shape, and our elision of their color and depth. In Lines, Lewitt entertains with his own perceptual play, this time in a spectrum of linear possibilities and relationships — from straight to wavy to dashed. His variations make us realize how, despite our daily immersion in lines, we still do not fully grasp their effect on our vision or on our mood. For Judd, differentials of line and plane and space inject all the value (quite literally a change in one quantity with respect to another) that “Specific Objects,” the title of the artist’s most famous essay from 1965, ever need.

At the end of the day, the work resists whatever we might think it resembles and pushes toward something more elemental and sublime. Judd’s Untitled (Black) is not a painting, a sculpture, a bench, or Darth Vader transformed into a fragment of the horizon. Gego’s print is not a skeleton or the mirage of a skeleton. Lewitt’s lines are not horizon lines. His rules are not rules. Martin’s grid is not perfect. Marden’s etching is not a column. Reinhardt’s contribution is Art as Art, as the title of his selected writings, published in 1991, puts it.

The Apollonian logic on display might alert us to the absorbing distraction and cacophony of the present. But is this the point? That art make us more “attentive”? If so, then this understanding of the project, should we call it minimalism or not (Judd persistently balked at the title, which he found inadequate and limiting if not outright wrong), remains dreadfully incomplete.

In Lines and Planes and Space, each artist may be reaching for a point where their work cannot be “deconstructed.” There is no hidden inner meaning. For the theorist Jacques Derrida, this is where art and justice overlap, paradoxically, in the very refusal to moralize, deliver a message, or promise a better life. These artists follow their own honed set of prompts and instincts through particular if irreducible (Martin might refer to our efforts here as a “bad guess”) physical, material, and philosophical constraints, gleaned from living and art. Their work seems incapable of being used for anything else.

In Bauhaus, Texas (1994), a documentary made near the end of Judd’s life, the art historian and curator Rudi Fuchs recounts Judd half-jokingly referring to himself as “the law” in Marfa — the west Texas town where he had purchased a few old airplane hangars, former Army offices and adjacent land, and built a second home for himself, his family, his friends, and their art. One could take offense, and many have. Still, Fuchs found in the candid comment a key to Judd’s work, “precise… very convinced of itself. Of course, on the other hand, what he makes is very fragile.”

Lines and Planes and Space exhibition installation. Photo courtesy of Krakow Witkin Gallery

Fragile indeed, for such a law as Judd conceives of it is not compatible with the variety of cute and practical domestic things on sale at IKEA, or the virtually endless recommendations to “declutter” and “live intentionally” — the main venues of minimalism today. When minimalism becomes positive, when it abandons art’s negative capabilities, it preaches self-improvement. The minimalism we find in these artists’ work is more like self-evacuation. Gego once said: “To visualize a solution is what matters: to make visible that which still does not exist outside of me.” And Martin often referred to herself as a mere tool beckoned by inspiration, with nothing personal (like ideas) cluttering the pursuit.

Stepping out of the elevator and into Lines and Planes and Space, this all feels distant. In the inviting top-floor serenity of the Krakow Witkin Gallery, we have to look up to see the sky. A bright blue and red copy of Reinhardt’s book joins the other artists’ seminal texts, manifestos and attempts to articulate the challenges they set for themselves in the story of art. We take a seat at the low, round coffee table, an out-west style hearth, and in the midst of art being displayed, packaged and sold, realize the rarity of such work today: art that asks nothing more of us than to be with it.

Helen Miller is an artist. She teaches at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design and Harvard Summer School. Michael Strand is a professor in Sociology at Brandeis University.