Jazz Album Review/Commentary: “Don Quixote’s Adventures in the World of Jazz” — Is Jazz Intrinsically Quixotic?

By Allen Michie

It’s hard to think of music that is more foolishly impractical than jazz, even with its pursuit of lofty ideals.

“Don Quixote’s Adventures in the World of Jazz: 200 Examples and a Few Remarks” by Hans Christian Hagedorn [Anales Cervantinos, Vol. 54 (2022), pp. 101-173]

Vince Mendoza and the Metropole Orkest, Olympians (Modern Recordings)

Scholar Hans Christian Hagedorn holding the issue of the journal Anales Cervantinos that features his article, “Don Quixote’s Adventures in the World of Jazz: 200 Examples and a Few Remarks.”

Miguel de Cervantes’s titular character from Don Quixote has joined the rarified ranks of those whose names have become adjectives, granting them a second level of immortality. Mssrs. Merriam and Webster tell us that “quixotic” means “foolishly impractical, especially in the pursuit of ideals; especially marked by rash lofty romantic ideas or extravagantly chivalrous action.” It’s hard to think of music that is more foolishly impractical than jazz, even with its pursuit of lofty ideals.

Hans Christian Hagedorn, a professor of German and Comparative Literature at Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha in Spain (literally a Man of La Mancha), undertook a romantically extravagant action by chivalrously listing every recorded instance — throughout the world, from 1925 to 2022 — where jazz musicians have been inspired by Don Quixote. There’s hardly anything “rash” about this, since Hagedorn has been working on this and related projects since 2016.

Often this is just the case of song titles but, as Hagedorn shows us, the transformation from 17th-century text to 21st-century music sometimes goes much deeper. His recent article in the journal Anales Cervantinos, “Don Quixote’s Adventures in the World of Jazz: 200 Examples and a Few Remarks,” is by necessity more quantitative than analytical. It “does not entail an in-depth analysis or an extensive description of each and every composition included in this register — a project of such dimensions would certainly require several books to be accomplished — but to perform a largely quantitative analysis of a list of 200 examples of jazz and jazz-inflected compositions related to Cervantes’ novel.” Hagedorn is careful to give the proviso that he is offering a “fairly broad overview of the topic.” He says this is not a list of every single jazz work relating to Don Quixtote, but he is far too modest. If this isn’t a definitive roll call of every jazz reference to Don Quixote then, as the song lyrics say, it will do until the real thing comes along.

Hagedorn takes a wide view. He includes some songs that may not be strictly jazz (such as various versions of “Dream the Impossible Dream” from Man of La Mancha, covered by many schmaltzy cabaret singers) and stretches into the avant-garde and hip-hop. His quixotic mission is to make the case that this isn’t just an exercise in accumulating trivia. “References to Don Quixote in jazz are not only frequent in the history of jazz, but there is a remarkable number of works in this genre that relate to the novel in very elaborate, complex, and meaningful ways, in the form of, to give just one example, larger works, such as suites,” Hagedorn argues.

One of the added benefits here is the tip on how to expand your own research. If you’re a bloodhound like me who sometimes starts following the trail of particular song covers, there’s much more available to you than Discogs, YouTube, and Spotify: Hagedorn made use of SoundCloud, Bandcamp, WorldCat, All About Jazz, AllMusic, Imusic, Jamendo, Jazzitalia, Taxi, and other global sources.

Of the 200 examples starting in 1925, two-thirds of them are from the 21st century. Apart from noting that recording technology has multiplied the amount of music across the board, Hagedorn admits “it would probably be too simple a thought, and possibly a mistake, to conclude that the interest of jazz musicians and composers in Don Quixote has increased dramatically over the past twenty-two years.” But the empirical evidence is undeniable that “interest in Cervantes’s masterpiece in general — and in the literary character of the Ingenious Gentleman of La Mancha in particular — has clearly not waned within the jazz world, but has actually grown.” (If you have any theories why, please leave them in the comments below.)

There are several other oddities. One is that there’s almost nothing from the Swing era. Nada from Duke Ellington, who composed the Such Sweet Thunder suite based on Shakespeare (a contemporary of Cervantes). There are no Quixote references at all throughout the ’30s, only one from the ’40s (by a Polish vocal ensemble), and only one from the ’50s.

A second oddity is the paucity of entries from Spain. Of the 39 nations dipping into Don Quixote for jazz material, Spain has only eight entries in almost 100 years. That’s fewer than Canada. (And to come up with even eight, Hagedorn digs waaay deep: one of the tracks is from 66 Whales, an avant-garde jazz/rock group from the Netherlands with a sole Spanish clarinet player). Hagedorn speculates that this may be due in part to the overall lack of much jazz culture in Spain, which had other things on its mind during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) and the Franco regime (1939-75), crucial periods for the development of jazz elsewhere. After 1975, many Spanish composers looked for inspiration anywhere except traditional Spanish culture.

A second oddity is the paucity of entries from Spain. Of the 39 nations dipping into Don Quixote for jazz material, Spain has only eight entries in almost 100 years. That’s fewer than Canada. (And to come up with even eight, Hagedorn digs waaay deep: one of the tracks is from 66 Whales, an avant-garde jazz/rock group from the Netherlands with a sole Spanish clarinet player). Hagedorn speculates that this may be due in part to the overall lack of much jazz culture in Spain, which had other things on its mind during the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) and the Franco regime (1939-75), crucial periods for the development of jazz elsewhere. After 1975, many Spanish composers looked for inspiration anywhere except traditional Spanish culture.

While it’s an overstatement to claim that “the history of jazz in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries could be traced through the musical adaptations and reverberations of Don Quixote,” it’s nevertheless true that there’s an impressive list of names that reverberate through Hagedorn’s essay and detailed notes: John Abercrombie, George Benson, Stanley Clarke, John Dankworth, Peter Erskine, Bill Evans, Art Farmer, Maynard Ferguson, Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Haden, Herbie Hancock, Dave Holland, Kenny Kirkland, Pat LaBarbera, Henry Mancini, Wynton Marsalis, John McLaughlin, Charles Mingus, Paul Motian, Marcus Printup, David Sanborn, Wayne Shorter, Horace Silver, Frank Sinatra, Sonny Stitt, Toots Thielemans, Jeff ‘Tain’ Watts, and Kai Winding, among many others (and I’m just listing the Americans, and the famous ones). It’s too bad that Chick Corea isn’t on the list, given his imaginative compositional scope and his skill at incorporating Spanish motifs into jazz. And you’ll just have to use your imagination for what our most Quixote-like jazz musician, Thelonious Monk, would have done with the spirit of Quixote and the rhythms of Sancho Panza’s donkey.

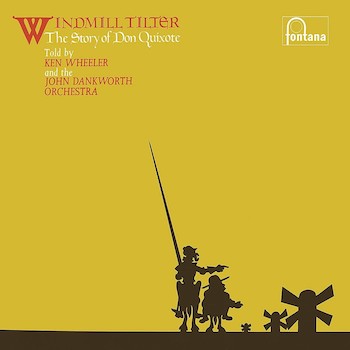

There’s a list of longer works, suites, and album-length treatments, many of which make a great list for future listening. I’m especially eager to hear Kenny Wheeler’s Windmill Tilter: The Story of Don Quixote with the John Dankworth Orchestra, Tom Harrell’s six-part suite Adventures of a Quixotic Character, and Ron Westray’s Chivalrous Misdemeanors with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra.

Then there are the individual tracks that are probably safely skipped, like “Don Quixote’s Hustle: A Disco Nightmare,” on John Serry’s Jazziz. Hagedon catches them all.

Is an epic quest for Don Quixote references in jazz a mad project? As Cervantes writes, “When life itself seems lunatic, who knows where madness lies? Perhaps to be too practical is madness. To surrender dreams — this may be madness. Too much sanity may be madness — and maddest of all: to see life as it is, and not as it should be!”

(You can read “Don Quixote’s Adventures in the World of Jazz: 200 Examples and a Few Remarks” here.)

The most recent entry in Hagedorn’s list, mentioned as upcoming at the time of publication, is Vince Mendoza’s “Quixote,” released this month on the album Olympians, a collaboration with the Dutch Metropole Orkest. Mendoza has written and arranged for the justifiably famous Metropole for 28 years now, and he served as its principal conductor from 2005 to 2013. Olympians is a selection of Mendoza’s works for the group, freshly arranged and rerecorded with a fine choice of guest artists.

The most recent entry in Hagedorn’s list, mentioned as upcoming at the time of publication, is Vince Mendoza’s “Quixote,” released this month on the album Olympians, a collaboration with the Dutch Metropole Orkest. Mendoza has written and arranged for the justifiably famous Metropole for 28 years now, and he served as its principal conductor from 2005 to 2013. Olympians is a selection of Mendoza’s works for the group, freshly arranged and rerecorded with a fine choice of guest artists.

The album opens with “Quixote,” a piece Mendoza recorded with the WDR Big Band in 2017 (video of the recording available here). It’s a powerful start: the full orchestra comes in with a bang, then it almost immediately quiets down to some simple shaker percussion. Mendoza adds strings effectively to his WDR arrangement, adding significant breadth and depth to the sound without sweetening it.

Given the occasion of this review, I tried hard to listen for anything particularly Don Quixotic in it. Perhaps it’s a failure of my imagination, but I’m not hearing much. There’s a kind of dizzy madness, possibly, in the brief twisting opening melody from the oboes, flutes, and piano (recalling something you might hear from the group Oregon), but there’s no real development of it from the orchestra. If the opening percussion is meant to sound Spanish, then why not use castanets? And why not use some assertive Spanish flamenco guitar instead of the subtle Andean charango (a kind of mandolin or ukulele)? The surging waltzing rhythm sounds more Germanic to me than Spanish. Listening to it, I see no windmills, ill-fitting clanking armor, complaining Sancho Panza, violent puppet shows, aching mouths where teeth used to be, ecstatic visions, evil enchanters, or treks across hot dry plains. I see colorful sailboats on a breezy day.

“House of Reflections,” however, could have plausibly been titled “Quixote.” Cécile McLorin Salvant powerfully delivers the poetic lyrics that Norma Winstone added to Mendoza’s 2013 composition:

We are lonely travelers

Through life’s dreams

Where do we go from here?

In this house of reflections

So many directions

Where’s my guiding star?

… Voices here, voices there

All try to tell you that you shouldn’t really care

Westering home through wind and rain

You know that the road you traveled can’t be traveled again.

The haunting melody even has traces of north African modes, suggesting the strong Moorish influence in 17th-century Spain. Perhaps the most expected thing the Knight of the Sad Countenance can do is turn up where he’s not expected.

There are many other pleasures on Olympians, aptly named for the excellence of the Metropole musicians and the guest soloists. It’s always grand to hear vocalist Dianne Reeves — especially on the same record with Cécile McLorin Salvant — because she has the dramatic authority to show these kids a thing or two. She’s one of our most emotive vocal improvisers, and her signature African-sounding scat syllables work well on “Esperanto,” lending a global perspective that’s in sync with Mendoza’s aesthetic. (“Take a good look at your own real life/And you’ll see if you want what you’ve got to be.” The wily Quixote appears once again?)

Vince Mendoza conducting Metropole Orkest. Photo: Reinout Bos

The less satisfying pieces sound like soundtracks in search of a movie. Mendoza is less of a developed-theme-and-variations composer than he is an imagistic combiner of textures and big sonic moments, like the soundtrack to a great hunt-and-chase scene in a film. His music is full of BAM! and POW! that come from nowhere, and while wham bam keeps the music striking and unpredictable, to my ear it sometimes comes at the expense of locating exactly what the melody is and where it’s going. An example is “Miracle Child,” a feature for Marc Scholten on fluid alto sax, contrasting the slow waltz with faster solo runs. There are plenty of dramatic swells from the orchestra, and Scholten rides the waves as they rise and fall. He has a beautiful alto tone, and it’s all lovingly recorded, mixed, and engineered. You won’t come away humming a standout melody, but you’ll be stimulated nevertheless.

I’ll end the review with a trip back to Spain. “Barcelona” has another one of Mendoza’s strong brass and string openings, then after 20 seconds there’s a quiet interlude with oboe voicings. Chris Potter carries the initial melody on tenor sax before passing it off to an electric guitar playing in a rock fusion ballad style. There’s a fine trumpet solo reminiscent of Freddie Hubbard’s arpeggios on Herbie Hancock’s “Maiden Voyage.” There are great readers in this band — the time signatures and diverse rhythms are sometimes locked in for just a few bars. I’m not sure how all the various glittering pieces fit together as a whole, however. Maybe the title is reflective of a fun and refreshing vacation in Barcelona, but otherwise I can’t hear a single suggestion of anything Spanish here.

“Take my advice and live for a long, long time. Because the maddest thing a man can do in this life is to let himself die,” writes Cervantes. May Don Quixote continue his long, wandering ride into jazz and popular music for generations yet to come, reminding us all to stay a little (as we say in our century) neurodivergent.

Allen Michie has a PhD in English Literature and works in higher education administration in Austin, Texas. He once wrote a paper in high school about how Don Quixote is characterized like his horse and Sancho Panza is characterized like his “burrow,” and his teacher wrote on the bottom, “Good paper, but you don’t know your ass from a hole in the ground.”

Tagged: Cécile McLorin Salvant, Cervantes, Dianne Reeves, Don Quixote, Hans Christian Hagedorn, Olympians

And I spent years and years telling freshmen to never begin their essays quoting a dictionary definition….

Why has jazz interest in Don Quixote increased dramatically over the past twenty-two years? Because the pursuit itself becomes more and more an act of chivalry. That is, an act done for its own sake and not for any potential reward.