Opera Album Review: A Major Baroque Opera in English Receives a Stylish Recording

By Ralph P. Locke

Aside from English pronunciation issues, the singers put over this remarkably polished and attractive opera by one of England’s great seventeenth-century composers with great panache, matching the superb instrumentalists.

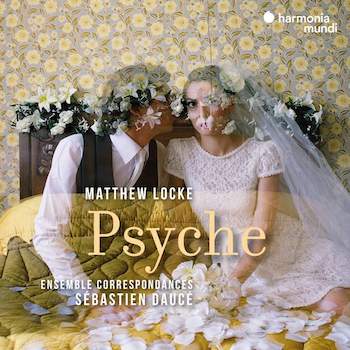

Matthew Locke: Psyche

Liselot de Wilde, soprano; Lucile Richardot, mezzo; Paul-Antoine Bénos-Djian, countertenor; Marc Mauillon, tenor; Étienne Bazola, bass-baritone

Ensemble Correspondances/ Sébastien Daucé

Harmonia Mundi 903325-6 [2 CDs] 107 minutes

To purchase or hear the beginning of each track, click here. Two short videos are here and here.

This is an aurally delightful production and a release to be welcomed by lovers of Baroque music and of opera. It’s also frustrating in one respect, as I’ll explain in a moment.

This is an aurally delightful production and a release to be welcomed by lovers of Baroque music and of opera. It’s also frustrating in one respect, as I’ll explain in a moment.

Matthew Locke (I’m not related to him!) was and has remained one of the most renowned seventeenth-century English composers of church and consort music. His dates are ca. 1621-77. He also was one of the first English composers to try to make something like operas in English. Psyche (1675) was his most thoroughgoing attempt at this. He and noted playwright Thomas Shadwell based the libretto on the spoken scenes and musical intermèdes in Molière’s play of that name (for which Lully composed the music). But, typically for English opera around that time, substantial sections of Locke’s Psyche were spoken, not sung. (Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas, now the only widely performed late-seventeenth-century English opera, was one of the few operas in English, during that era, to be entirely sung.)

Locke’s opera comes down to us without the many instrumental numbers, mainly dances. These were composed by Giovanni Battista Draghi. The musical director of Ensemble Correspondances, keyboardist Sébastien Daucé, looked around and couldn’t find other Draghi numbers that could substitute appropriately for the lost ones, so he used instrumental pieces by Locke, thereby providing (he argues in his essay) greater stylistic unity. (But perhaps the result loses, I suppose, some stylistic variety! Oh, well, the results are musically persuasive, and there’s more than one way to . . . revive a score that survives only incompletely, as the opera world has decided with regard to, say, Puccini’s Turandot.)

Locke was a highly accomplished composer, and there are pleasures aplenty to be had here. I particularly enjoyed the scene involving two pairs of “despairing lovers”; also the scene for Vulcan and four cyclopses, all of whom hammer away in music that, in its clomping vigor, anticipates the Sailors’ Song in Purcell’s Dido. For comparison to Locke’s scene for four “despairing lovers,” the performers here immediately offer the equivalent scene from Lully’s Psyché; this stalls the action for the listener but nicely points out what was being done in opera on the Continent around the same time. (Lully’s opera, from 1675, is freely based, likewise, on Molière’s play; in it Lully incorporated much of the music that he had composed for that play.)

English Baroque composer Matthew Locke. Photo: Wiki Common.

The playing of Ensemble Correspondances is brilliant and multi-hued. The singers are of the highest caliber and are alert to all kinds of dramatic nuances in the text. There are thirteen of them, taking dozens of roles, many of which occur in only one scene. One of my favorites is Marc Mauillon (as Mars, among other characters), whom I had greatly admired in the Bru Zane recording of Offenbach’s La Périchole (see my review).

But my frustration, to which I alluded at the beginning, comes from the fact that these are all — to judge by their French and Flemish names — Continental singers trying to put an English text across. Some (e.g., Lucile Richardot and Licelot de Wilde) manage quite well. But others create sounds that I could make no sense of without glancing at the libretto. The problem often resides in a singer’s never having mastered the glottal stop (as between two successive vowels: “they are”). Also, some singers (including Mauillon and baritone Renaud Bres; all the baritones here are listed in the booklet as “basse”) have trouble with short vowels: black becomes “bleck”, misery “meezery”, and ‘tis “tease.”

By contrast, I was able to understand, unaided, much of what was sung by native-born Brits in the recent recording of Lampe’s The Dragon of Wantley (reviewed here).

I should mention that pronunciation problems largely disappear when all the singers join as a chorus. Either those passages were rehearsed more carefully, or the singers with better pronunciation out-articulate the others, conveying the verbal message to the listening ear.

The plot is carried out in speech and onstage action (summarized in the libretto; I wish it had been printed entire). Briefly, the central character, the beautiful Psyche — who only speaks, and thus is not heard on the recording — arouses the envy of Venus, who likes to think of herself as unrivaled in physical attractiveness. Venus puts Psyche through a series of disturbing trials, such as exposing her to a threatening dragon, plunging her into the sea, and tempting her with a box containing noxious fumes.

Sébastien Daucé and Ensemble Correspondances. Photo: courtesy of the artists.

The musical numbers consist of a series of dances, arias (duets, etc.), and choruses largely involving characters who assault Psyche, assist her, confuse her, transport her elsewhere, and so on. These numbers often amount to a series of supernatural incidents involving river gods, nymphs, the aforementioned cyclopses, some furies, Envy, and so on. Venus does sing occasionally, as do Pan, Mars, Apollo, and those groups of furies and such, but, as I said, Psyche does not, nor does her lover Cupid (Venus’s son).

Because the spoken dialogue is omitted, you can enjoy listening here, uninterruptedly, to more than an hour and a half of highly accomplished music from the middle Baroque era, spectacularly well performed. But, if you want to understand what is going on at any moment, you’ll probably need to follow the booklet closely and read the summaries of the (unrecorded) spoken dialogue.

What I heard here is splendid, and it makes me hope that some smallish opera company or music-school opera studio (say, at the New England Conservatory?) will pick up this remarkably polished and attractive opera by one of England’s great Baroque-era composers — preferably with singers who can put the English words across not just with flair but with total clarity.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Ensemble Correspondances, Ensemble Correspondances/ Sébastien Daucé, Harmonia Mundi, Licelot de Wilde, Lucile Richardot, Matthew Locke, Psyche, Ralph P. Locke