Visual Arts Review: The Dazzling Vodou Flags of Myrlande Constant

By David D’Arcy

It is stunning to see these flags of beads and sequins on cloth, and the adjectives keep on coming — hypnotic, baroque, beguiling, hallucinatory.

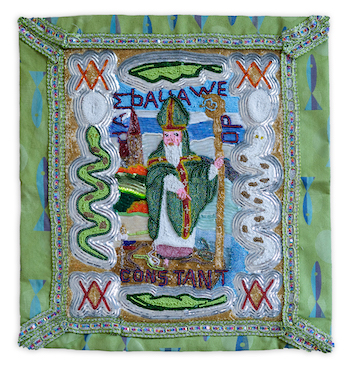

Myrlande Constant, Saint Patrick. Photo: David D’Arcy

One of the dozen vodou flags by Myrlande Constant in the show Drapo (through March 25), at Fort Gansevoort in New York City, is a scene with St. Patrick, clad in green, with snakes on each side.

For outsiders like myself observing Haitian art, St. Patrick is the last figure that you might expect to see in a Haitian context — improbable, akin to seeing tropical creatures in a snow-globe — but the inclusion of the saint who rid Ireland of its snakes attests to the infinitely expanding universe of vodou, or voodoo, as it tends to be called in this country. St. Patrick and St. Nicholas of Bari (a version of Santa Claus) have their place as figures around which vodou scenes are built, constructed with beads that Constant gives the feel of brushstrokes.

It is stunning to see these flags of beads and sequins on cloth, and the plaudits keep on coming — hypnotic, baroque, beguiling, hallucinatory. Constant’s show in New York has been an important event this year. Her upcoming retrospective, which opens March 26 at the Fowler Museum at UCLA in Los Angeles, will offer even more — works on a grand scale which will surprise her admirers and challenge those who are viewing them for the first time. Note — the show in NY is free, as is the museum exhibition in Los Angeles.

Constant, who is staying with friends in Philadelphia during the show, says that she paints with beads. The painterly power of her flags is dizzying. The works are complex constructions that also operate, like sculptural reliefs, in three dimensions. As in religious pictures and ancient reliefs (the upcoming Constant retrospective in Los Angeles compares them to religious and mythological paintings), the figures become increasingly familiar from flag to flag. The longer you look, the easier it becomes to take in the skills of Constant and her team that keep up with her restless imagination.

Myrlande Constant is 54 and grew up in the Haitian countryside. Her family migrated to Port au Prince, the capital, where her mother worked in a rudimentary factory making wedding dresses. Her father was a vodou priest — flags traditionally fly outside vodou temples.

Turning peasants with little or no land into ill-paid garment proletarians seemed like progress to Haiti’s president at the time, Jean-Claude Duvalier, known as Baby Doc. Constructing those dresses involved elaborate beading, which Myrlande learned by virtue of having no place else to go. She herself refined the practice of beading dresses in those workshops until, she says, the oppressive conditions and low pay drove her away. Bear in mind that, for a woman with paid employment in Haiti to leave a job (except to emigrate), those conditions must have been wretched. Still, Constant eventually achieved what few Haitians can accomplish without leaving their country: she created a workshop to make and transform a traditional object. In a desperately poor country, ungovernable these days, she and her team create objects that radiate with a glorious elegance.

The New York show is at Fort Gansevoort, a multistory gallery located in a tourist mall of eateries that had once been the meatpacking district. Constant’s latest works are her largest ever, all the better for telling stories.

One such work is the flag Ezuli Dantor, named after the lwa, or spirit, who is associated with female power. The dark-skinned woman is holding a dark-skinned child dressed in beaded finery — a reference to the Christian Madonna and Child, or more specifically to the Black Madonna of Czestochowa. One theory holds that the Madonna motif came from Polish soldiers brought to Haiti by the French to suppress slave revolts, who then changed sides. Constant’s flags often blend multiple legends. This image of mother and child is surrounded by beads that form a frame on the fabric, a portal to the spiritual world. We see the same kind of doorway, with snakes on each side, in Constant’s flag depicting St. Patrick. She seems to be telling us that the spiritual world has its own borders and architecture, which feel all the more material because the beadwork is in three dimensions.

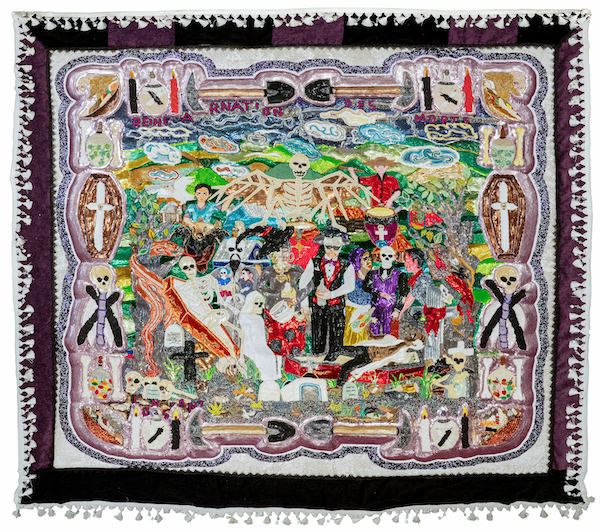

Myrlande Constant, Réincarnation des Morts. Photo: David D’Arcy

We are given a different view of the spiritual realm in Réincarnation des Morts (“Reincarnation of the Dead”), a mural-sized depiction of a cemetery, a place where the dead make their presence known, outnumbering the living. Beads in white and other bone-like colors predominate. A beaded frame of coffins and skeletons in the picture delineates the layout of the spiritual real estate.

Given the violent chaos in Haiti right now, and the absence of an economy that provides for survival for many, art-making is remarkably active, even though tourists aren’t around to buy anything. Besides Constant, whose work is now sought internationally, there is the movement called Atis Rezistans, composed of artists and children drawn from the poorest of the poor who assemble works from materials on the streets. The human skull is a recurring object and motif. For years Atis Rezistans has marketed itself shrewdly and shamelessly, organizing an event called the Ghetto Biennale, its own version of the Salon des Refusés of 19th-century Paris. Found objects are repurposed as distillations of the ravaged landscape or figures that seem to have risen out of it. Anything but realistic, these creations still remind you where they came from.

Constant has exhibited with Atis Rezistans — Haitian artists abroad tend to get thrown together into group shows — but her flags, especially these late ones in the Fort Gansevoort show, are more about harmony than decay. Her imagined worlds hold together — there’s enough space on the flags to fill them with characters as well as the profusion of symbols that surrounds them.

And Constant herself has landed in another world, the art market. Her flags will now reach the same museums and collectors who bought the stylish “quilts” that the Ghanaian artist El Anatsui commissions teams in his country to make from discarded soda cans. If Constant approaches El Anatsui’s must-have status among collectors (and she seems headed for that), the prices for her work will be very high. Constant should have already been recognized as a national treasure in Haiti. But success can be a liability for anyone who wants to return to work there.

David D’Arcy lives in New York. For years, he was a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He writes about art for many publications, including the Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at the Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.